You’re sitting on the couch, scrolling through your phone, and you decide to check your smartwatch. Your heart rate is 72 beats per minute. Solid. Then you see a post from a pro cyclist whose resting heart rate (RHR) is sitting at a cool 38. It feels like their heart is barely even trying. Honestly, it’s enough to make anyone wonder if their own ticker is working too hard.

The short answer? Yes. Athletes have lower heart rate numbers because their cardiovascular system has undergone a massive physical transformation. It’s not just "being fit." It's biology.

Why the question "do athletes have lower heart rate" matters for your health

When we talk about resting heart rate, we are looking at the number of times your heart beats per minute while you're completely at rest. For most adults, a "normal" range is between 60 and 100 bpm. But for someone who spends ten hours a week in the pool or on a bike, those numbers drop off a cliff.

This isn't an accident. It's an adaptation.

The heart is a muscle. If you work your biceps, they get bigger. If you work your heart through consistent aerobic exercise, the heart walls—specifically the left ventricle—get thicker and stronger. This allows the heart to push out more blood with every single squeeze. This is called stroke volume.

Think of it like this: If you have a small bucket, you have to dip it into the well twenty times to fill a trough. If you have a massive industrial-sized bucket, you only need five dips. The athlete’s heart is that massive bucket. Because it’s so efficient, it doesn’t need to beat 70 times a minute to keep the body oxygenated. Forty beats will do just fine.

The Science of Athletic Bradycardia

In the medical world, a heart rate below 60 bpm is technically called bradycardia. Usually, that’s a red flag for doctors. It can mean the heart's electrical system is failing or the pump is dying. But for a marathoner? It’s a badge of honor.

👉 See also: Why Your Best Kefir Fruit Smoothie Recipe Probably Needs More Fat

We call this Athletic Bradycardia.

It’s not just about muscle size, though. There’s a hidden player here: the autonomic nervous system. Your heart rate is controlled by a tug-of-war between the sympathetic nervous system (fight or flight) and the parasympathetic nervous system (rest and digest). Training shifts the balance. High-level athletes often have a much higher "vagal tone." The vagus nerve acts like a brake on the heart. In athletes, that brake is pressed down a little harder, keeping the engine idling at a much lower RPM.

A 2017 study published in the Journal of Applied Physiology looked at senior athletes and found that even as they aged, their heart rates remained significantly lower than their sedentary peers. This suggests that the remodeling of the heart isn't just a temporary "pump" you get at the gym; it's a structural change that can last decades.

Is there such a thing as too low?

Here is where it gets tricky. You might think a RHR of 30 is the ultimate goal. But there is a point where efficiency turns into a medical curiosity, or even a risk.

In 2013, researchers began looking more closely at "The Athlete’s Heart." They found that extreme endurance training can sometimes lead to an increased risk of atrial fibrillation (Afib) later in life. While a low heart rate is generally a sign of a bulletproof cardio system, if it’s accompanied by dizziness, fainting, or chest pain, it’s no longer "athletic." It’s a problem.

Take the case of legendary cyclist Miguel Induráin. His resting heart rate was reportedly 28 bpm. Twenty-eight! That is incredible, but for a normal person, that’s a trip to the ER for a pacemaker. The difference is how the body handles the load. Induráin’s body was perfectly adapted to that low rate because his stroke volume was gargantuan.

✨ Don't miss: Exercises to Get Big Boobs: What Actually Works and the Anatomy Most People Ignore

Not all sports are created equal

Don't expect a world-class powerlifter to have the same heart rate as a cross-country skier.

- Endurance Athletes: Marathoners, triathletes, and rowers usually have the lowest RHRs. Their training is all about sustained oxygen delivery.

- Strength Athletes: While fit, their hearts undergo a different kind of stress (pressure loads rather than volume loads). Their RHR is often lower than the average person's, but rarely in the 30s or 40s.

- Sprinters/Power Athletes: These folks sit somewhere in the middle.

The heart responds specifically to the type of "insult" you give it. Long, slow runs build that large, elastic chamber. Heavy squats build a thicker, high-pressure pump.

How to lower your own heart rate (The right way)

You don't need to be an Olympian to see these benefits. Even moderate increases in activity can move the needle.

First, stop checking your pulse every ten minutes. It changes based on caffeine, stress, sleep, and even whether you have a full bladder. To get a real reading, check it the moment you wake up, before you even get out of bed.

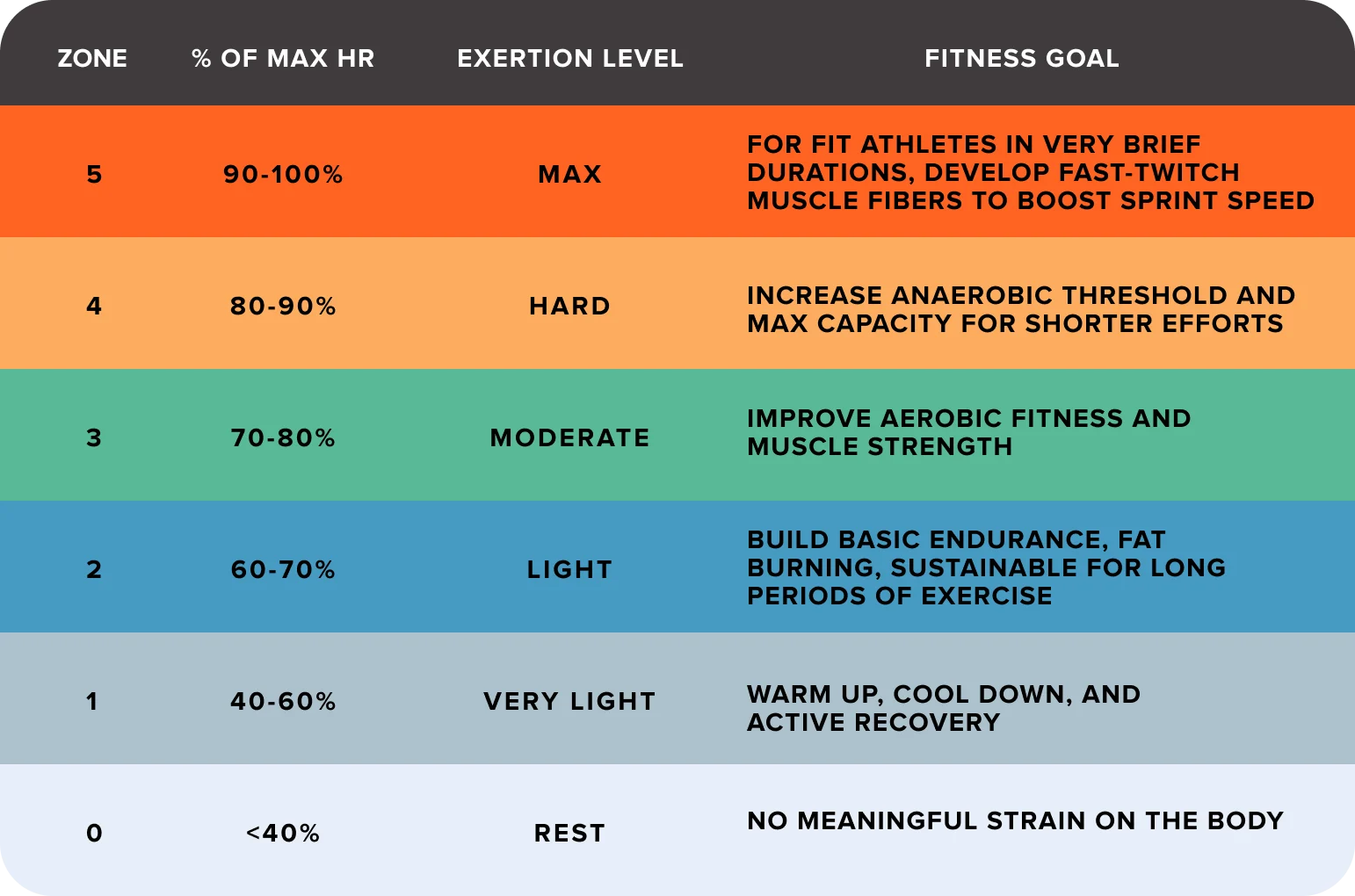

If you want to see that number drop, you need to focus on Zone 2 training. This is the "conversational pace" where you can talk but you’d rather not. It’s the sweet spot for cardiac remodeling. If you always train at 100% intensity, you’re mostly building power and glycolytic capacity, not necessarily the massive stroke volume that leads to a lower RHR.

Real-world factors that mess with the numbers

Let's be real for a second. Genetics plays a massive role. Some people can run 50 miles a week and never see their heart rate dip below 55. Others hit 45 bpm just by looking at a pair of running shoes.

🔗 Read more: Products With Red 40: What Most People Get Wrong

Age is another factor. As we get older, our maximum heart rate drops. The "220 minus age" formula is a bit of a blunt instrument, but the trend is real. Interestingly, RHR doesn't necessarily have to climb as you age if you stay active, but the heart’s ability to rev up like a Ferrari engine definitely slows down.

Overtraining is the secret heart rate killer. If you wake up and your RHR is 10 beats higher than it was yesterday, your body is screaming at you. It means your nervous system is fried and you haven't recovered from your last session. In this case, a higher heart rate in an athlete is a sign of weakness, not strength.

Summary of the "Athlete Heart" phenomenon

It basically comes down to efficiency.

A lower heart rate in athletes is the result of a bigger pump (stroke volume) and a more dominant "braking" system (parasympathetic tone). It’s a sign that the body has become a specialist at moving oxygen. While 40 bpm would be scary for someone who hasn't exercised in years, it’s just another Tuesday for a distance runner.

Actionable Steps for Improving Heart Health

If you're looking to optimize your own cardiovascular efficiency, keep these specific points in mind:

- Prioritize Volume Over Intensity: To see structural heart changes, aim for at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic work per week. Think brisk walking, light cycling, or swimming.

- Monitor Sleep Quality: Your heart rate won't drop if your body is in a constant state of inflammation. Aim for 7-9 hours of sleep to allow the autonomic nervous system to reset.

- Track Trends, Not Moments: Don't freak out over one high reading. Look at your weekly average RHR. If it's trending down over three months, your training is working.

- Hydrate for Blood Volume: Your heart has to work harder to pump "sludge" (dehydrated blood). Keeping your blood volume up through proper hydration and electrolyte balance makes the heart's job significantly easier.

- Consult a Professional: If your heart rate is consistently below 50 and you feel sluggish, tired, or dizzy, get an EKG. It's better to confirm it's "Athletic Bradycardia" than to assume and miss an underlying heart block.