He’s the guy with the sinister whisper and the scar. If you grew up watching the 1971 classic, Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory, Arthur Slugworth was likely your first introduction to corporate espionage, or at least to the idea that a stranger in a trench coat might offer you a fortune for a piece of candy. He hangs out in the shadows of every city where a Golden Ticket is found. He creeps up on children. He promises them enough money to buy a new house if they just deliver one tiny thing: the Everlasting Gobstopper.

But here is the thing about Arthur Slugworth that most people forget until they rewatch the movie as adults. He isn't actually a villain. Well, he isn't the villain he pretends to be.

In the world of Roald Dahl, and specifically the cinematic adaptation directed by Mel Stuart, Slugworth represents the ultimate test of character. He is the personification of greed, looming over Charlie Bucket and the other four children like a vulture. Yet, the reveal at the end of the film—that "Slugworth" is actually an employee of Wonka named Mr. Wilkinson—changes everything we thought we knew about the stakes of the tour. It wasn't just about who could stay out of the chocolate river; it was a deep-cover psychological operation.

The Man, The Myth, The Fake Spy

In the original book, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Arthur Slugworth is a real rival. He’s a competing chocolatier who actually did send spies into Wonka’s factory to steal recipes. That's why Wonka closed the gates in the first place. He was tired of his genius being pilfered by guys like Slugworth, Prodnose, and Fickelgruber. But in the 1971 movie, the director decided to give this background character a face and a physical presence.

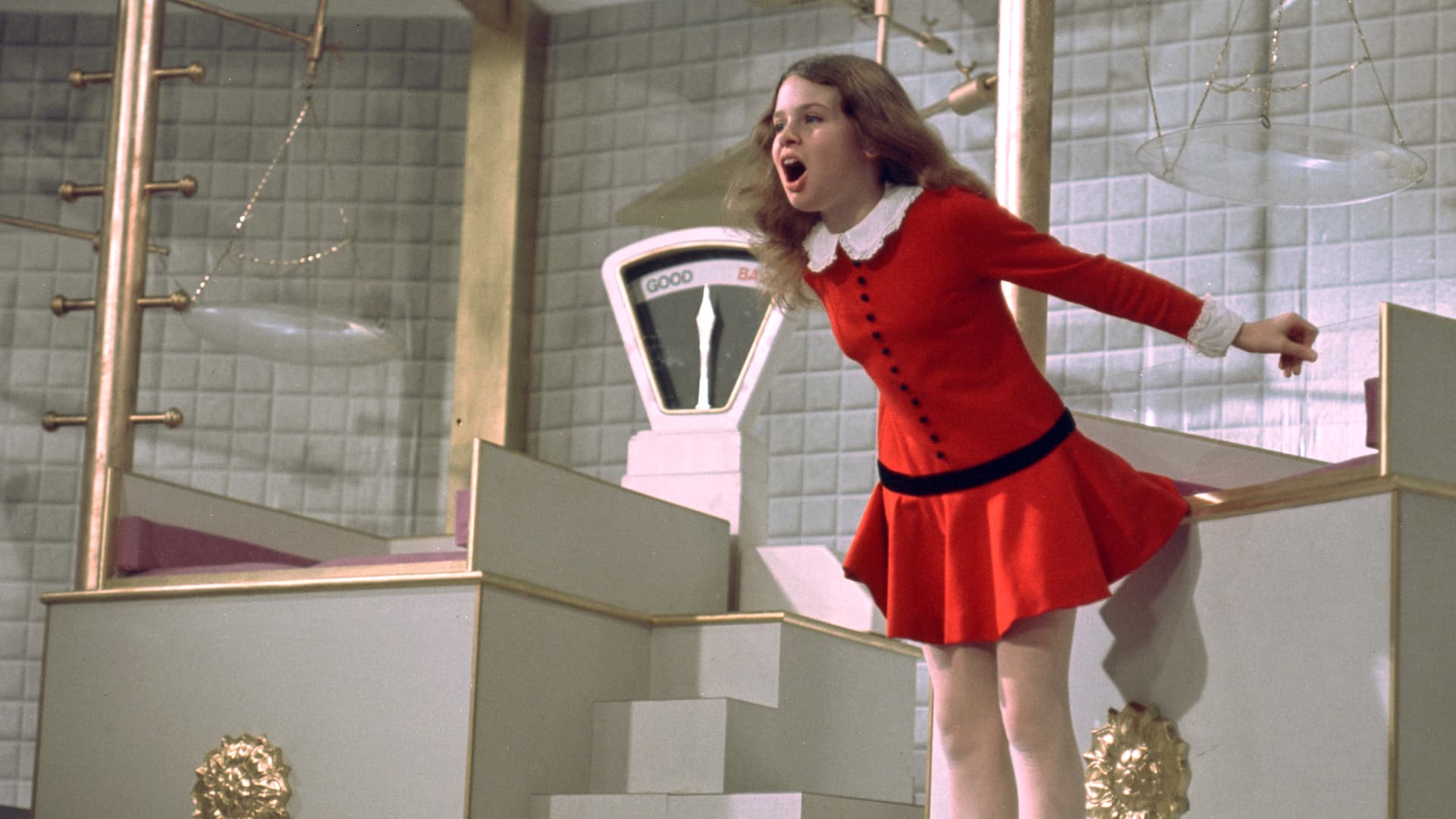

They cast Günter Meisner, an actor who had a natural ability to look incredibly menacing while saying very little. Meisner's performance is what makes the character work. He doesn't scream. He doesn't threaten. He just offers. "A secret for a secret," he basically tells the kids. Honestly, it’s a terrifying tactic for a child to face. You have Veruca Salt, who is already a monster of entitlement, and then you have Charlie, who is literally starving. For Charlie, the temptation Slugworth presents is actually logical. It isn't just about being "bad"; it’s about survival.

Why the 1971 Version Diverged from Dahl

Roald Dahl famously hated the 1971 film. He hated the music, he hated Gene Wilder’s casting (he wanted Spike Milligan), and he likely wasn't a fan of the "Slugworth Test." In the book, the children lose because they are simply bratty and succumb to their own vices. There is no undercover agent lurking in the wings.

📖 Related: The A Wrinkle in Time Cast: Why This Massive Star Power Didn't Save the Movie

But the movie needed a narrative "ticking clock." By introducing Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory Arthur Slugworth as a physical entity who meets the children before they even enter the factory, the filmmakers raised the stakes. It created a moral dilemma that followed Charlie into every room. Every time Wonka turned his back, the audience wondered: Is Charlie going to do it? Is he going to take the Gobstopper?

The Psychology of the Everlasting Gobstopper

Let's talk about the Gobstopper for a second. It is the perfect MacGuffin. It’s a candy that never gets smaller and never loses its flavor. For a business rival, that’s a death sentence. If everyone owns one piece of candy that lasts forever, nobody ever needs to buy candy again.

When Wonka hands these out in the Inventing Room, he’s handing out his most dangerous secret. He knows it. He also knows that Wilkinson (fake Slugworth) has already "bought" the loyalty of the other four kids. Or has he? We see the other kids interact with him, and it’s clear they are all in. Veruca probably would have sold Wonka’s soul for a nickel, and Mike Teavee was too obsessed with technology to care about corporate ethics.

The Moral Pivot Point

The climax of the movie isn't when Charlie flies in the Great Glass Elevator. It’s the moment right before that, in Wonka’s office. Wonka is screaming. He’s terrifying. He calls Charlie a "crook" and a "cheat" because of the Fizzy Lifting Drinks incident. He tells him he gets nothing. "Good day, sir!"

This is the moment where Charlie should have turned to Slugworth. He had every reason to be angry. Wonka was being a jerk. Charlie had the Gobstopper in his pocket. He could have walked out, met the man with the scar, and handed over the candy for the money his family desperately needed.

👉 See also: Cuba Gooding Jr OJ: Why the Performance Everyone Hated Was Actually Genius

Instead, he walks up to Wonka’s desk and puts the Gobstopper down.

That act of honesty—returning the "stolen" goods even after being treated unfairly—is the only reason Charlie wins. It’s only then that Wonka softens, his entire demeanor changing in a heartbeat. He calls for Mr. Wilkinson, and the terrifying Slugworth walks through the door, no longer looking like a spy, but like a tired office worker in a suit.

Why the Character Still Works Today

We live in an era of "twists," but the Slugworth reveal is one of the cleanest in cinema history. It recontextualizes the entire movie. It turns the factory tour from a whimsical field trip into a high-stakes job interview.

There are several reasons why this specific subplot remains the strongest part of the 1971 film's structure:

- Internal vs. External Conflict: Most of the kids fail because of internal flaws (gluttony, pride). Charlie is the only one who faces an external temptation that could actually help his family. This makes his victory much more earned.

- The Shadow of Corporate Greed: Even as a kid, you understand that Slugworth is "bad business." He represents the guy who wants to win without doing the work.

- The Visual Storytelling: The way Meisner is filmed—often in low-angle shots with harsh lighting—contrasts perfectly with the bright, colorful world of the factory. He is the "real world" intruding on the fantasy.

Actually, it’s kind of funny when you think about the logistics. How did Wilkinson get to every country so fast? Veruca is in the UK, Augustus is in Germany, Charlie is in... well, some vaguely European-American town. Wilkinson must have a world-class travel agent and a lot of frequent flyer miles to beat the news crews to every location.

✨ Don't miss: Greatest Rock and Roll Singers of All Time: Why the Legends Still Own the Mic

Common Misconceptions About the Character

People often confuse the movie version with the book version. In the 2005 Tim Burton remake, Slugworth is barely a footnote, closer to his book counterpart. He doesn't have a big role because that movie focuses more on Wonka’s daddy issues and flashy visuals.

But for fans of the 1971 version, Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory Arthur Slugworth is an icon. Some fans have even theorized that the "Slugworth" persona was based on real historical industrial spies. In the early 20th century, candy companies were notoriously secretive. Milton Hershey and the Mars family were famous for their rivalries and guarded recipes. Dahl wasn't just making up the idea of candy spies; he was satirizing a very real, very cutthroat industry.

How to Apply the "Slugworth Test" to Real Life

While you probably aren't being asked to steal secret candy recipes by a man with a scar, the "Slugworth Test" is actually a pretty solid framework for ethics. It’s about what you do when you think no one is watching and when you have every reason to be resentful.

If you're looking to dive deeper into the lore, here are a few things you can do to appreciate the nuance of this character:

- Watch the 1971 film specifically for Wilkinson's reactions. Once you know he's an employee, watch his face when he talks to the kids. You can almost see him judging them.

- Compare the book vs. the movie. Read the original Roald Dahl text to see how much more "hopeless" the world feels when there is no test, just inevitable failure for the greedy.

- Research Günter Meisner. He was a prolific German actor who often played villains, but his turn as "Slugworth" is arguably his most enduring contribution to Western pop culture.

Basically, the character of Arthur Slugworth serves as the moral anchor of the story. Without him, Charlie is just a kid who didn't get stuck in a pipe. With him, Charlie is a hero who chose integrity over a payday. That’s a distinction that makes the movie more than just a psychedelic musical; it makes it a lesson in human character that still rings true today.

Actionable Insight: The next time you find yourself in a situation where you feel "wronged" by a system or a boss, remember the Gobstopper. Integrity isn't about how you act when things are going well; it's about how you act when you have a "Slugworth" offering you an easy way out of a hard situation. Keeping your "Gobstoppers" and staying true to your values is usually what leads to the "Glass Elevator" moments in life.