He sits in the shadows. You can barely see him at first—just a pale, shaved head emerging from the gloom of a Cambodian temple. When we finally meet the Apocalypse Now Colonel Kurtz, he isn’t the monster we expected. Or maybe he’s exactly the monster we feared. He’s peeling an orange. He’s splashing water on his face. He is a man who has looked into the sun and refused to blink, and now he's just waiting for someone to kill him.

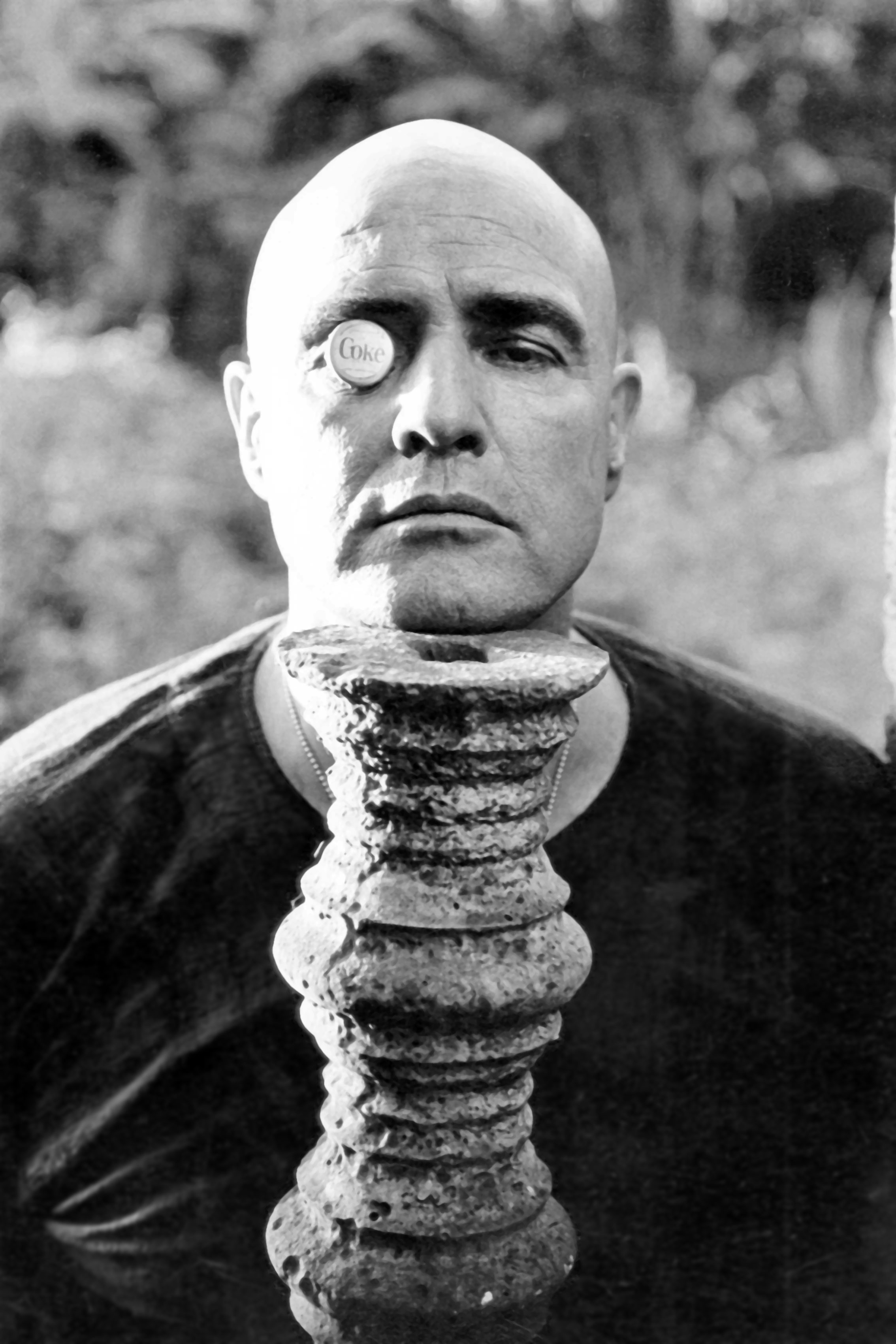

Francis Ford Coppola’s 1979 masterpiece didn't just give us a war movie. It gave us a psychological breakdown caught on 35mm film. At the center of that collapse is Walter E. Kurtz. Played by a famously difficult, overweight, and unprepared Marlon Brando, the character became something much larger than the script intended. He became a symbol of what happens when the "civilized" mind stops lying to itself.

The Man Who Went Too Far

The setup is simple enough, though the execution was legendary chaos. Captain Willard (Martin Sheen) is sent upriver to "terminate with extreme prejudice" the command of Colonel Kurtz. Why? Because Kurtz went rogue. He stopped taking orders from Saigon. He started fighting the war his own way, with a private army of Montagnard tribesmen who treat him like a god.

But here is the thing: Kurtz was the best they had. He was a West Point graduate, a decorated hero, a man destined for the Joint Chiefs of Staff. He wasn't some low-level grunt who snapped. He was the elite. When the Apocalypse Now Colonel Kurtz decided that the American way of waging war was a hypocritical joke, the military establishment didn't just lose a soldier. They lost their moral cover.

The horror.

That's the famous line, right? Borrowed straight from Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, which served as the loose blueprint for the film. In the book, Kurtz is a colonial ivory trader. In the movie, he’s a Special Forces officer in the Vietnam War. The shift in setting changes the stakes. In Vietnam, the "horror" wasn't just the violence. It was the realization that the people calling the shots back in Washington or Saigon were more insane than the man living in the jungle.

👉 See also: Is Heroes and Villains Legit? What You Need to Know Before Buying

Brando, the Shadows, and the Script That Didn't Exist

Let's talk about the production. It's impossible to understand the Apocalypse Now Colonel Kurtz without knowing the disaster behind the scenes. Marlon Brando showed up to the set in the Philippines weighing over 300 pounds. He hadn't read the script. He hadn't read Conrad’s book. Coppola was devastated. He had envisioned a lean, mean warrior.

What followed was a week of stalling. Coppola and Brando sat in a trailer, talking for days, while the crew waited and the budget spiraled out of control. They realized they couldn't film Brando in full light—he didn't look like a starving jungle god. So, cinematographer Vittorio Storaro used the shadows.

It was a happy accident.

By keeping Kurtz in the dark, he became a myth. We see a hand. We see the top of a bald scalp. We hear that voice—that low, rhythmic, almost musical mumble. Brando improvised much of his dialogue, including the famous monologue about the "pile of little arms." It’s gruesome. It’s haunting. And honestly, it’s some of the best acting in cinema history precisely because it feels like a man talking to himself in a fever dream.

The Philosophy of the Hollow Man

Why do we still care about Kurtz? Why does this specific character resonate decades later?

✨ Don't miss: Jack Blocker American Idol Journey: What Most People Get Wrong

It's because Kurtz represents the breaking point of the human psyche. He talks about "the will." He tells Willard about seeing North Vietnamese soldiers cut off the arms of children who had been vaccinated by the Americans. He says he wept, but then he realized: if he had ten divisions of men who could do that—who could be "moral" and yet "utilize their primordial instincts to kill without mercy"—then the war would be won in a day.

He's not a sociopath in the traditional sense. He's a man who saw a logic so pure and so terrifying that it broke his connection to humanity. He calls the American generals "grocery clerks" who want to wage a "clean" war. Kurtz argues that if you are going to commit to the act of killing, you must do it without judgment. You must make a friend of horror.

Most people get Kurtz wrong. They think he's just a crazy guy in the woods. But Willard realizes, as he reads Kurtz’s dossier on the boat trip upriver, that Kurtz was actually making sense. That’s the real "horror." The man wasn't wrong about the hypocrisy of the war; he was just too honest about it.

The Cultural Weight of the Horror

The impact of the Apocalypse Now Colonel Kurtz stretches far beyond film buffs. You see his DNA in everything from Colonel Skarsgård characters to the gritty "rogue commander" tropes in video games like Spec Ops: The Line.

But Kurtz is different because he’s so still. He doesn't scream. He doesn't have an "evil plan." He isn't trying to take over the world or even win the war anymore. He’s just waiting. He has created a kingdom of death because he can no longer live in a world of lies.

🔗 Read more: Why American Beauty by the Grateful Dead is Still the Gold Standard of Americana

The film's ending—Willard rising from the water like a primitive spirit to strike Kurtz down—isn't a victory. It’s a ritual. Kurtz wants Willard to do it. He wants to die "as a soldier," not as a broken old man. When Willard swings that machete, he isn't saving the world. He’s just fulfilling Kurtz’s last order.

How to Watch Kurtz Today

If you’re going to revisit the Apocalypse Now Colonel Kurtz, don't just go for the "Final Cut" or the "Redux" because you think longer is better. Many fans argue the original 1979 theatrical cut handles the mystery of Kurtz best. The more time you spend with him, the more "human" he becomes, and Kurtz works best when he feels like a force of nature.

Pay attention to the sound design. Walter Murch, the sound editor, did something incredible with Kurtz’s scenes. The background noise of the jungle—the insects, the distant chanting—often drops out when Kurtz speaks. It forces you into his head. You’re trapped in the temple with him.

Honestly, the best way to understand the character is to look at the real-life inspirations. Coppola often pointed to Tony Poe, a real CIA paramilitary officer who reportedly dropped severed heads on enemy villages to scare them. The reality of the Vietnam War was often as dark as the fiction. Kurtz is just the concentrated essence of that darkness.

Actionable Insights for the Cinephile

To truly appreciate the depth of the Apocalypse Now Colonel Kurtz, you need to look beyond the surface level of the movie. The character is a gateway into a much deeper exploration of power and madness.

- Read the source material: Pick up Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. It’s short, dense, and will show you exactly how Coppola translated 19th-century colonialism into 20th-century warfare.

- Watch the documentary: Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker's Apocalypse is mandatory viewing. It shows the footage of Brando and Coppola arguing and reveals how much of Kurtz was created on the fly.

- Analyze the lighting: Next time you watch, notice how Kurtz is never fully lit. This "chiaroscuro" effect isn't just for style; it represents his fractured soul—part hero, part demon.

- Listen to the "Manuscrit" recordings: There are rare recordings of Brando’s actual improvisations. They are rambling, strange, and occasionally brilliant. They show the raw material that was carved into the character we see on screen.

Kurtz isn't just a movie villain. He is a warning. He reminds us that the line between a "hero" and a "monster" is often just a matter of how much of the truth we are willing to admit. He died in the jungle, but the questions he asked about morality, war, and the human heart are still being answered today.