If you think the Brontë sisters are all about moors, ghosts, and "Reader, I married him," you’ve probably overlooked the most radical book of the bunch. The Tenant of Wildfell Hall is different. It doesn't just flirt with darkness; it drags the Victorian domestic nightmare into the light.

It's raw. Honestly, it's pretty brutal.

While Charlotte was writing about the internal yearning of Jane Eyre and Emily was busy making Heathcliff a gothic icon, Anne was doing something much more dangerous. She was writing the truth about what happened behind closed doors in England’s "respectable" homes. She wasn't interested in making it pretty. She was interested in making it real.

The Mystery of the Woman in the Widow's Weeds

The story kicks off with a vibe that feels like a modern psychological thriller. A mysterious woman named Helen Graham moves into a ruinous old mansion called Wildfell Hall. She’s got a young son, a serious "do not disturb" aura, and a talent for painting. Naturally, the local village of Linden-Car goes into a gossiping frenzy. They think she’s a widow. They think she’s a fallen woman. They think she’s hiding something.

They're right about the last part.

Gilbert Markham, a local farmer who’s a bit full of himself, gets obsessed. He falls for her. But Helen isn't some damsel waiting to be rescued by a farm boy. She’s a survivor. When she finally hands Gilbert her diary, the novel shifts gears from a rural mystery to a visceral account of an abusive marriage.

Anne Brontë wasn't playing around. She describes the degradation of Helen’s husband, Arthur Huntingdon, with a clinical, unflinching eye. He’s a drunk. He’s a philanderer. He brings his mistress into their home and asks Helen to teach her how to be a "good" woman. It’s sickening.

💡 You might also like: Why Love Island Season 7 Episode 23 Still Feels Like a Fever Dream

Why Charlotte Brontë Tried to Bury This Book

Here is the weirdest part of the story. After Anne died in 1849, her own sister, Charlotte, basically tried to erase The Tenant of Wildfell Hall from existence.

Charlotte blocked the republication of the novel. She claimed that the subject matter was "an entire mistake." She felt it was too bold, too coarse, and that Anne didn't really understand what she was writing. Honestly? Charlotte was probably terrified. The book was a scandal. It challenged the very foundation of Victorian law—the idea that a woman was the legal property of her husband.

In 1848, a woman leaving her husband wasn't just a social faux pas. It was kidnapping. By taking her son and fleeing, Helen Graham was technically stealing her husband’s property. Anne was advocating for a woman’s right to agency in a way that made even her progressive contemporaries flinch.

- Fact: The novel sold out in weeks upon its first release.

- Fact: Many critics at the time called it "revolting" and "unfit for a lady."

- Fact: Anne’s preface to the second edition is one of the most famous defenses of realism in literature. She famously said, "I would rather whisper a few wholesome truths therein than utter unmeaning gibberish."

The Gritty Reality of Arthur Huntingdon

Most Victorian villains are caricatures. Not Arthur. He’s terrifying because he starts out as a "charmer." He’s the guy every girl thinks she can change. Helen thinks she can save him with her piety and love. Spoiler: She can't.

Anne watched her brother, Branwell Brontë, destroy himself through addiction. She saw the lies, the mood swings, and the physical decay. She put all of that into Arthur. When Arthur dies at the end of the novel—slowly, painfully, and in total terror of what comes next—it’s not a moment of triumph. It’s a tragic, messy ending to a wasted life.

It’s also where Anne’s controversial theology comes in. She believed in universal salvation. She thought that even a man as "bad" as Arthur could eventually be redeemed in the afterlife after a period of suffering. This was heretical stuff back then. People were obsessed with the idea of eternal hellfire. Anne basically said, "No, God is better than that."

📖 Related: When Was Kai Cenat Born? What You Didn't Know About His Early Life

This Isn't Just a "Classic"—It’s Modern

If you read The Tenant of Wildfell Hall today, you’ll be shocked at how relevant it feels. It deals with gaslighting before there was a word for it. It looks at the cycle of addiction. It examines how men are socialized to be toxic to one another.

There’s a scene where Arthur and his friends are drinking, and they try to force a young boy to drink too. They think it’s funny. They want to make him a "man." Helen stops them. She actually gives her son a tiny bit of alcohol mixed with something bitter to make him hate the taste. She’s literally trying to immunize him against the lifestyle that killed his father.

It’s a "feminist" novel, sure, but it’s also a deeply "human" one. It asks if we can ever really know another person. It asks if love is enough to overcome a broken character. Usually, in 19th-century fiction, the answer is yes. In Anne’s world, the answer is "probably not, so you better have a backup plan."

What Most People Get Wrong About Anne

People call her the "quiet" sister. They think she’s the boring one.

That is such a massive misunderstanding. Anne was the bravest of the three. She went out into the world as a governess more than the others. She saw the dark underbelly of the upper classes firsthand. While her sisters were writing about the heights of passion, Anne was writing about the survival of the soul.

The structure of the book is even a bit experimental. You have a frame narrative (Gilbert’s letters), then the diary (Helen’s voice), then back to the frame. It’s a nested doll of perspectives. It forces you to see Helen through the eyes of a man who doesn't understand her, and then through her own eyes, where the truth is much darker.

👉 See also: Anjelica Huston in The Addams Family: What You Didn't Know About Morticia

How to Actually Read The Tenant of Wildfell Hall Today

Don't go into this expecting a cozy period piece. It’s not Pride and Prejudice. There are no balls or witty banter about dowries. Well, there is a little, but it’s usually tinged with bitterness.

If you want to get the most out of it, focus on the dialogue. Anne has a way of making her characters sound incredibly modern. When Helen stands her ground against her husband’s demands, her arguments are logical, sharp, and devastating. She doesn't cry and faint. She stands there and tells him why he’s wrong.

Actionable Steps for the Modern Reader

If you're ready to dive into this masterpiece, here is how to approach it without getting bogged down in the "classic literature" fog:

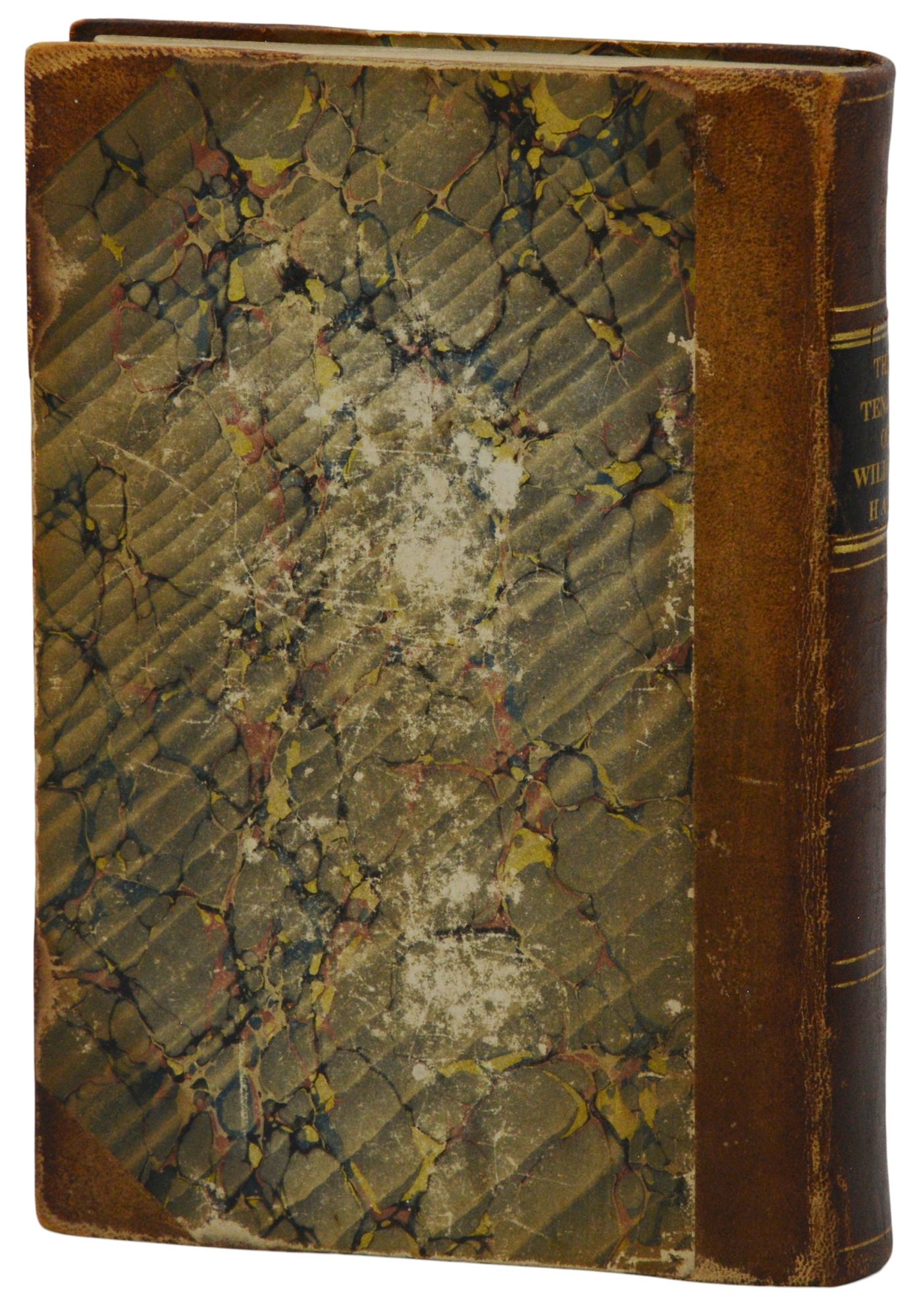

- Get a good annotated edition. Look for the Oxford World's Classics or Penguin Classics version. The footnotes help explain the crazy Victorian laws that make Helen’s escape so much more high-stakes than it seems.

- Read the Preface. Anne’s 1848 preface to the second edition is a fire manifesto. It explains exactly why she wrote the book and why she didn't care if people found it "unladylike." It sets the perfect tone for the rest of the read.

- Watch the 1996 BBC Miniseries. If you're a visual learner, Tara Fitzgerald plays Helen Graham perfectly. It captures the gloom of Wildfell Hall and the claustrophobia of Helen’s marriage brilliantly. It’s a great way to "prime" your brain before tackling the text.

- Compare it to Agnes Grey. If you want to see Anne's range, read her first novel too. It’s shorter and focuses on the life of a governess. Seeing them together shows you just how much she grew as a writer in a very short time.

- Look for the "Universalism" themes. Keep an eye out for when Helen talks about religion. It’s the key to her character. Her strength comes from a belief system that was radical for its time—the idea that no one is beyond hope, but everyone must face the consequences of their actions.

Anne Brontë died at 29. She only wrote two novels. But with this one, she left behind a blueprint for the "social novel" that writers are still using today. She proved that you don't need ghosts or monsters to write a horror story. Sometimes, the most terrifying thing in the world is just a man with a glass of brandy and a legal right to your life.

Read it. It’ll change how you look at the Brontës forever.

Key Takeaways:

- Anne Brontë was the most realistic and socially radical of the Brontë sisters.

- The Tenant of Wildfell Hall was a direct challenge to Victorian marriage laws and social hypocrisies.

- The novel was so controversial that Charlotte Brontë suppressed its publication after Anne's death.

- It remains one of the first truly feminist novels in the English canon, focusing on female agency and the harsh reality of domestic abuse.

- The book is a psychological study of addiction and recovery that remains shockingly relevant.