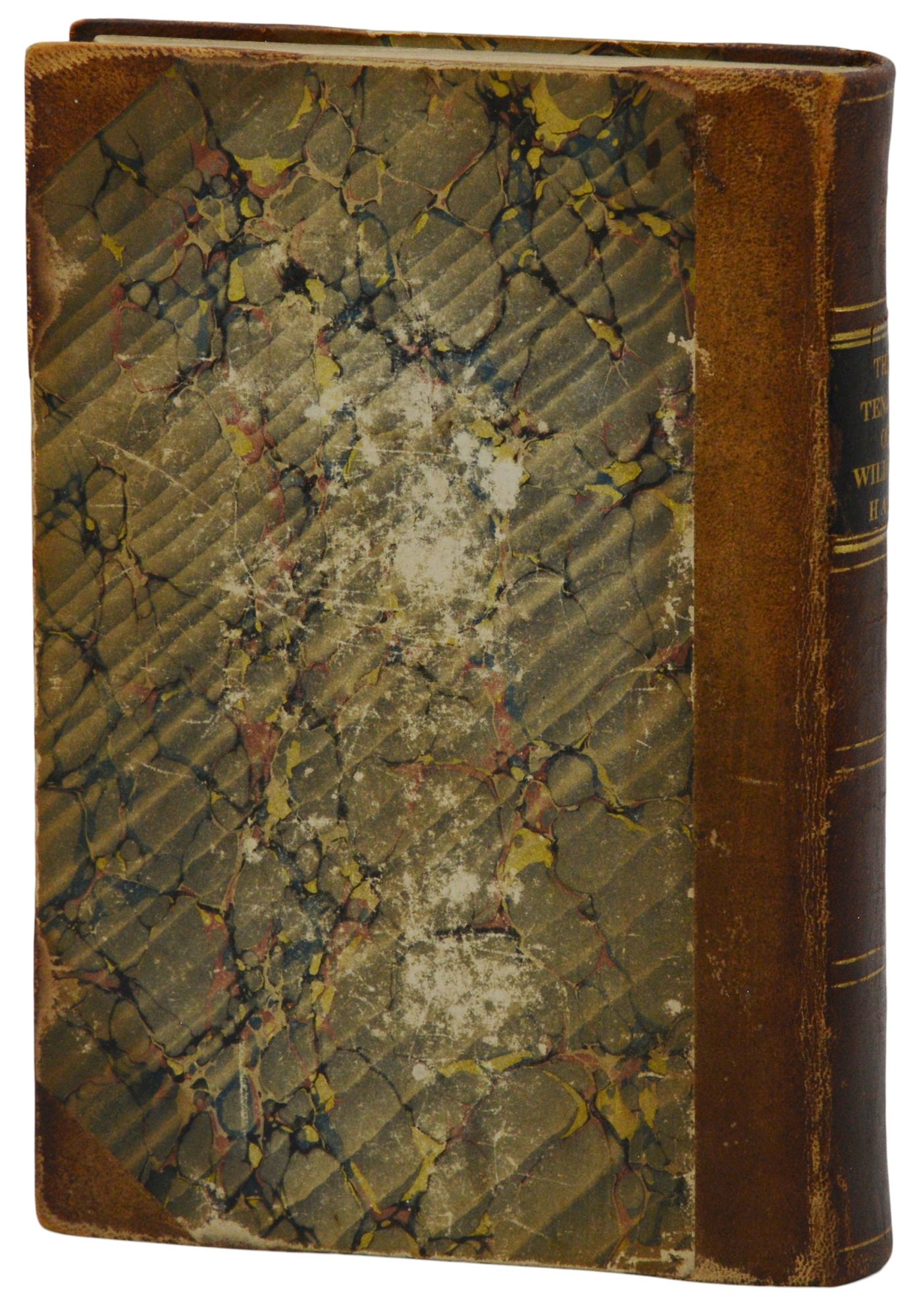

Charlotte got the fame. Emily got the mystique. But Anne? Honestly, Anne Brontë wrote the book that actually mattered for the real world. While her sisters were busy dreaming up brooding, toxic heroes like Rochester and Heathfield—men who frankly needed a lot of therapy—Anne was looking at the wreckage of Victorian marriages and telling the brutal, unvarnished truth. The Tenant of Wildfell Hall wasn't just a novel; it was a 19th-century whistleblow.

It’s hard to overstate how much this book pissed people off in 1848.

Imagine picking up a book expecting a flowery romance and instead finding a visceral depiction of chronic alcoholism, psychological abuse, and a woman slamming a bedroom door in her husband's face to stay safe. Critics at the time called it "coarse" and "revolting." Even Charlotte, Anne's own sister, tried to suppress the book after Anne died, claiming it was a mistake born of a "gentle, retiring" girl seeing too much misery. Charlotte was wrong. Anne knew exactly what she was doing.

The Tenant of Wildfell Hall: A Victorian Domestic Horror Story

Most people know the basic premise: a mysterious widow named Helen Graham moves into a dilapidated mansion called Wildfell Hall with her young son. She’s secretive. She paints to make a living. She refuses to play by the social rules of the local village. Naturally, the neighbors gossip. The "hero," Gilbert Markham, falls for her, but then he discovers her secret through her diary.

The middle of the book is where things get heavy.

We find out Helen isn't a widow. She’s a runaway wife. She fled her husband, Arthur Huntingdon, a man who spent his days drinking himself into stupors and bringing his mistresses into their home. In 1848, a woman doing this was literally a criminal. Under the law of "coverture," a woman's legal existence was folded into her husband's. Her money was his. Her body was his. Her children were his property. By leaving, Helen Graham was stealing herself and her son from their "rightful owner."

Anne didn't write this to be edgy. She wrote it because she watched her brother, Branwell Brontë, destroy himself through addiction. She saw the "gentlemanly" vices of the era up close and decided to stop pretending they were romantic.

✨ Don't miss: The Lil Wayne Tracklist for Tha Carter 3: What Most People Get Wrong

Why Helen Graham is the realest character in 19th-century fiction

Think about the stakes here.

Helen doesn't just leave because Arthur is mean. She leaves because he starts teaching their toddler son to drink alcohol and curse. That was the breaking point. She realized that staying in a toxic environment for the sake of "duty" was actually a sin. That’s a massive theological shift for a mid-Victorian writer. Anne was a devout Christian, but she believed in Universal Salvation—the idea that everyone eventually gets to heaven. This belief gave her the moral courage to argue that no one should be trapped in an earthly hell just to satisfy a social contract.

The controversy that nearly erased Anne from history

When the book came out, it was an instant bestseller. It sold out faster than Jane Eyre. But the backlash was swift. The Spectator complained that the author seemed to have a "morbid love of the coarse, if not of the brutal."

Then Anne died at only 29.

Charlotte Brontë, surviving her sisters, took over the literary estate. When the publisher wanted to reprint The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, Charlotte said no. She wrote that the book was a mistake and didn't represent Anne's true nature. Because of that choice, Anne was sidelined for over a century. She was remembered as the "quiet one," the "third Brontë," the one who wasn't as talented as her sisters.

Actually, she was just the one who was too brave for her time.

🔗 Read more: Songs by Tyler Childers: What Most People Get Wrong

Modern readers are finally catching up

If you read the book today, it feels startlingly modern. It’s basically a psychological thriller about gaslighting. Arthur Huntingdon is a textbook narcissist. He uses charm to lure Helen in, then spends the rest of the marriage tearing her down, isolating her, and blaming her for his own failings.

The structure of the book is also wild. It’s a frame narrative—a story within a story within a letter. This isn't just a fancy literary trick. It forces the reader to confront the difference between how men talk about women (Gilbert’s perspective) and the lived reality of a woman's life (Helen’s diary).

The gritty details of Victorian addiction

Anne Brontë didn't hold back on the physical reality of Arthur’s decline. This wasn't the "poetic" consumption or a tragic, beautiful death. It was ugly. It involved bile, tremors, and a terrified man realizing his body was failing him.

Historians like Juliet Barker have pointed out how closely this mirrored Branwell Brontë’s collapse. Anne was the one who had to deal with the fallout. She was the one who saw the wreckage. By putting it in a book, she broke the Victorian code of silence. You didn't talk about "gentlemen" behaving that way. You certainly didn't show a woman being strong enough to walk away from it.

How to approach reading it for the first time

Don't expect the sweeping moors and ghostly whispers of Wuthering Heights. This is a much more claustrophobic book. It’s grounded. It’s "lifestyle" in the sense that it’s about the daily grind of survival in a bad situation.

- Skip the intro if you want to avoid spoilers. Most modern editions have long introductions that reveal the entire plot.

- Pay attention to the art. Helen is a professional artist. This was one of the few ways a woman could actually make money back then. Anne treats Helen's career with total respect; it’s not a hobby, it’s her literal ticket to freedom.

- Watch the doors. There’s a famous scene where Helen locks her bedroom door against Arthur. It’s a simple act that was profoundly revolutionary in 1848. It asserted her right to her own body.

Anne's legacy in 2026

We’re finally in an era where Anne is being recognized as a pioneer of feminist literature. She wasn't just writing "romance." She was writing about social justice, legal reform, and the psychology of abuse long before those terms were part of the cultural lexicon.

💡 You might also like: Questions From Black Card Revoked: The Culture Test That Might Just Get You Roasted

The "quiet" Brontë was actually the loudest.

She stood up to her sisters, her critics, and the legal standards of her country. She insisted that if a man is a monster, you don't have to save him. You can just leave. That’s a message that still resonates, maybe even more now than it did then.

Actionable insights for Brontë fans

If you're looking to dive deeper into Anne’s world, start with the 1996 BBC miniseries starring Toby Stephens and Tara Fitzgerald. It captures the grimness perfectly. Then, read her poetry. It’s much more melancholic and searching than her sisters' work.

To truly understand The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, you have to look at the laws of the time. Research the "Custody of Infants Act 1839." You'll realize that Helen Graham wasn't just a fictional character; she was a representative of thousands of real women who had no legal right to their own children if they left an abusive husband. Anne was writing for them.

The best way to honor Anne Brontë is to stop seeing her as a secondary figure. Pick up the book. Read the diary entries. Witness the door being locked. It’s a masterpiece of grit and courage that deserves every bit of the recognition it was denied for a hundred years.

- Read the 1848 Preface: In the second edition, Anne wrote a preface defending her work. It’s one of the best "mic drop" moments in literary history.

- Visit Scarborough: While the other Brontës are buried in Haworth, Anne is buried by the sea in Scarborough. It’s a fittingly independent end for the sister who went her own way.

- Compare the "Heroes": Line up Arthur Huntingdon next to Heathcliff and Rochester. Ask yourself who is the most realistic portrayal of a "bad boy." The answer is always Anne’s version.

The reality is that Anne Brontë wrote the most dangerous book of the 19th century. It’s time we treated it that way.