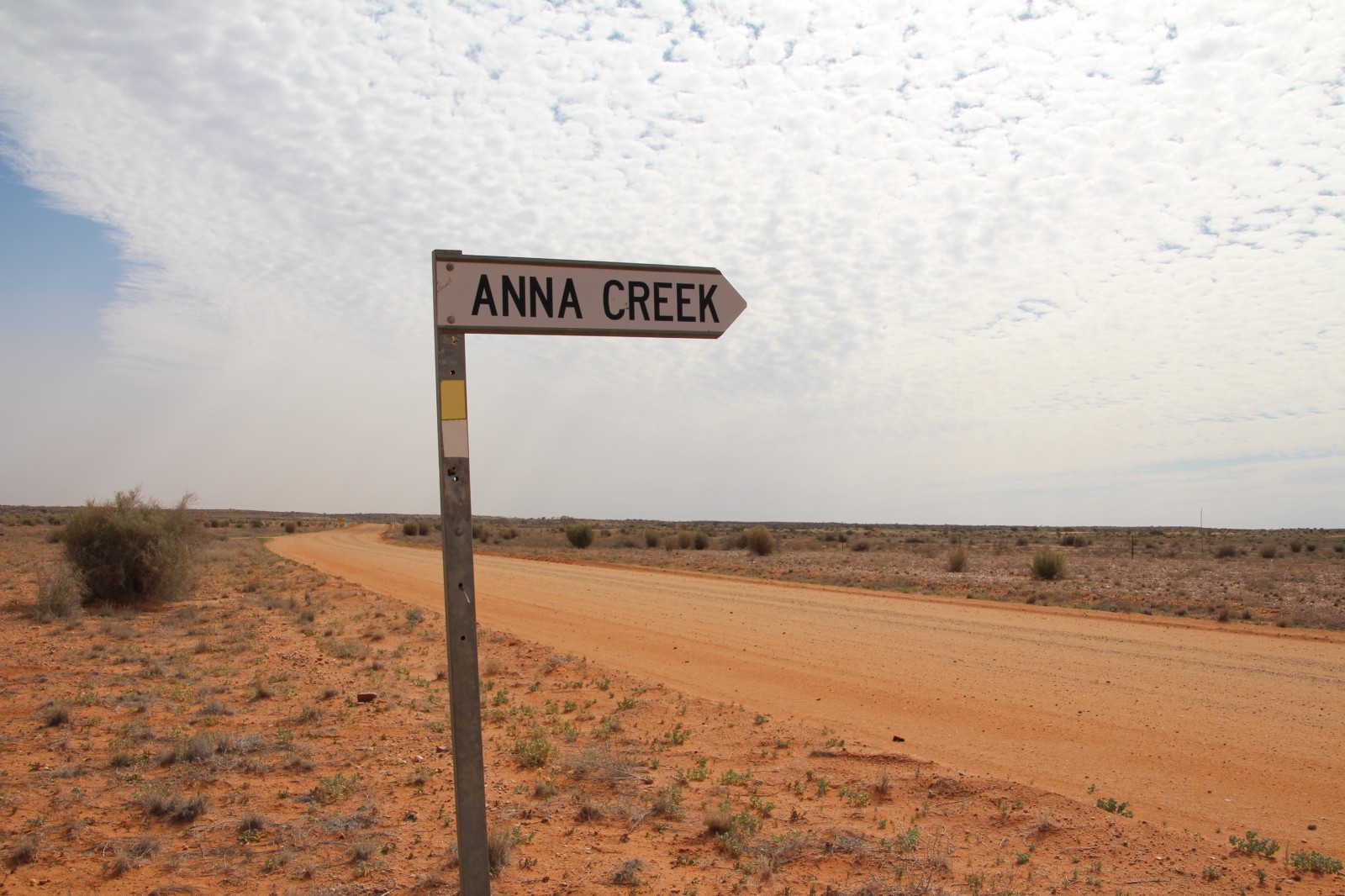

You’ve seen the images online. Usually, they’re wide-angle shots of a dusty horizon, maybe a lone Land Cruiser kicking up a red plume of dirt, or a group of ringers huddling near a yard. But here’s the thing about anna creek station photos: they lie. Not because they’re faked, but because the human eye and a camera lens can’t actually process the sheer, terrifying scale of a place that is larger than the entire country of Israel.

Anna Creek Station sits in the heart of South Australia’s Lake Eyre Basin. It covers roughly 23,677 square kilometers. That’s about 5.8 million acres. If you tried to walk across it, you’d probably die before you hit the halfway mark. It’s a landscape of extremes, where the soil is so dry it cracks into hexagonal plates, yet it can transform into an inland sea overnight if the rains up north in Queensland play ball.

Honestly, it’s hard to wrap your head around a "farm" that big. Most people see the photos and think "outback Australia," but it’s more like its own sovereign territory with its own weather systems and logistical nightmares.

The Visual Reality of the World's Biggest Cattle Run

When you start digging into anna creek station photos, you’ll notice a recurring theme: the "nothingness." But look closer at the work of photographers like Peter Brew-Bevan or the historical archives from the Kidman era. There is a specific texture to the ground here. It’s the "gibber" plain—millions of small, wind-polished stones that look like they’ve been varnished.

Back in the day, Sir Sidney Kidman, the "Cattle King," bought this place as part of a strategic chain of properties. He wanted to move cattle from the north to the markets in Adelaide without them losing weight. If one station was in drought, he’d just move the herd to the next. Anna Creek was the crown jewel of this empire, and even now, under the ownership of the Williams family (Williams Cattle Company), it remains a titan of the industry.

You won't find many lush green paddocks here. The photos mostly show saltbush and bluebush. These plants are the secret to why the cattle don't just keel over. They are incredibly hardy, salt-tolerant shrubs that provide nutrition when the grass is long gone.

Why the Colors Look Different in Real Life

If you’re looking at anna creek station photos on a high-definition screen, the reds might seem oversaturated. They aren't. The iron oxide in the soil is so intense that at sunset, the entire horizon looks like it’s actually on fire. It’s a phenomenon called "albedo," where the ground reflects the sky's light, creating a purple-and-orange sandwich that looks like a bad Photoshop job.

💡 You might also like: Super 8 Fort Myers Florida: What to Honestly Expect Before You Book

Most of the "hero shots" of the station are taken at the William Creek Hotel. It’s technically an enclave within the station. It’s basically the only place where a tourist can get a beer and a burger for hundreds of miles. The walls are covered in business cards and old bras—a stark, messy contrast to the pristine, silent desert just ten feet outside the door.

Logistics That Look Like Military Maneuvers

Photography of the muster is where the action is. In a "normal" ranch, you might use a few dogs and a quad bike. At Anna Creek, they use R22 helicopters.

Imagine trying to find 10,000 head of cattle across an area the size of a small nation. You can’t do it from the ground. The photos of the mustering process often capture "the push"—thousands of Santa Gertrudis and Angus-cross cattle being funneled toward portable yards. The dust clouds are massive. Pilots fly just feet above the scrub, using the engine noise to nudge the stubborn bulls. It’s dangerous, high-stakes work that costs a fortune in aviation fuel.

- The Fleet: It isn't just one truck. It’s road trains. Three or four trailers long.

- The Staff: Usually around 15 to 20 people. Think about that. 20 people managing 23,000 square kilometers.

- The Water: It’s all about the Great Artesian Basin. Without those bores (wells) tapping into ancient underground water, nothing survives.

The bores are a huge part of the visual identity of the station. You'll see photos of these lonely pipes sticking out of the ground, surrounded by a green oasis of weeds and happy cows. These are the lifeblood of the operation. If a bore pump fails in mid-summer when it's 48°C (about 118°F), cattle start dying within 24 hours.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Landscape

People assume it’s a flat, boring desert. It’s not.

Actually, the topography is incredibly varied. You’ve got the Denison Range, which looks like a jagged spine of rock rising out of the dust. Then you have the sand dunes of the Tirari Desert creeping onto the eastern edges. Some anna creek station photos show the "Mound Springs"—natural geothermal vents where water bubbles up from the Earth’s crust, creating weird, conical hills that look like miniature volcanoes.

📖 Related: Weather at Lake Charles Explained: Why It Is More Than Just Humidity

These springs are sacred to the Arabana people, the traditional owners of the land. Their history on this country goes back tens of thousands of years, long before Kidman showed up with his checkbook. Any modern discussion or visual record of the station that ignores the Arabana connection is missing the soul of the place. They see the "tracks" in the land that a camera lens simply can't pick up.

Capturing the "Long View"

The sheer isolation is the hardest thing to photograph. How do you take a picture of silence?

Photographers often use drones now to get a "God’s eye view" of the homestead. The homestead itself is like a small village. It has its own workshop, schoolroom, and massive cold storage. It has to be self-sufficient. If you run out of milk, you don't go to the corner store. You wait two weeks for the mail plane or the supply truck.

A lot of people search for anna creek station photos because they want to see the scale compared to human objects. Look for the photos of the main gate. It looks like any other gate, but the fence line attached to it runs for hundreds of kilometers. The station has over 3,000 kilometers of fencing. Maintaining that is a full-time job for a "fencer" who might live in a remote hut for weeks at a time.

The Seasonal Shift: From Dust to Deluge

If you want the most dramatic anna creek station photos, you have to look for the flood years. 2010, 2011, and 2019 saw water from the Diamantina and Georgina rivers flow down into Lake Eyre.

Suddenly, the dusty gibber plains are covered in yellow wildflowers. The dry creek beds (which are usually just lines of gum trees in the sand) become raging torrents. Pelicans appear by the thousands. It’s eerie. You’re in the middle of one of the driest places on Earth, and you’re surrounded by water birds.

👉 See also: Entry Into Dominican Republic: What Most People Get Wrong

The contrast is jarring. One year, a photo shows a cow standing over a dry bone; the next, that same spot is waist-deep in clover. This "boom and bust" cycle is the only way the station survives. They bank the grass in the good years to survive the five-year droughts that inevitably follow.

Actionable Insights for Planning a Visit (or a Shoot)

If you are planning to head up the Oodnadatta Track to see this for yourself, keep a few things in mind. You can't just drive onto the station. It’s private property, a working business, and they don't take kindly to tourists getting bogged in their back paddocks.

- Base yourself in William Creek. It’s the gateway. You can take scenic flights from here, which is the only way to truly see the station's layout.

- Timing is everything. Go between May and August. Any other time, the heat will melt your camera (and your resolve).

- Golden hour is real. Because there’s no pollution and no city lights, the "blue hour" after sunset lasts forever. This is when the desert textures really pop in photos.

- Respect the work. If you see a road train or a mustering team, stay out of the way. These guys are working in some of the harshest conditions on the planet.

The true value of anna creek station photos isn't in their aesthetic beauty. It's in the evidence of human grit. It’s the fact that anyone manages to run a profitable business in a place that seems actively trying to kill anything that moves.

When you look at these images, don't just look at the horizon. Look at the wear and tear on the equipment. Look at the cracked skin on the ringers' hands. Look at the way the cattle huddle under a single, pathetic tree. That’s the real Anna Creek. It’s not a postcard; it’s a battleground.

Moving Forward with Your Outback Research

To get a better handle on the reality of the station, stop looking at stock photography. Search for the social media tags used by actual station hands and helicopter pilots who work the season. Their "behind the scenes" shots of broken axles, 3 a.m. starts, and the occasional pet joey give a much more honest account than any professional travel brochure.

If you're a photographer, bring a polarizing filter to cut the glare off the gibber stones and a dust-proof bag for every single piece of gear you own. The dust here is "bull dust"—it's finer than talcum powder and it will find its way into your lens sensors and your soul.

Check the latest pastoral reports from the South Australian government if you're interested in the environmental impact or the current stock numbers. Understanding the carrying capacity of the land changes how you "see" the photos. You start to realize that a "crowded" photo of cattle is actually a sign of a very small, specific gathering point, because across the rest of the 23,000 square kilometers, there’s likely not a soul in sight.