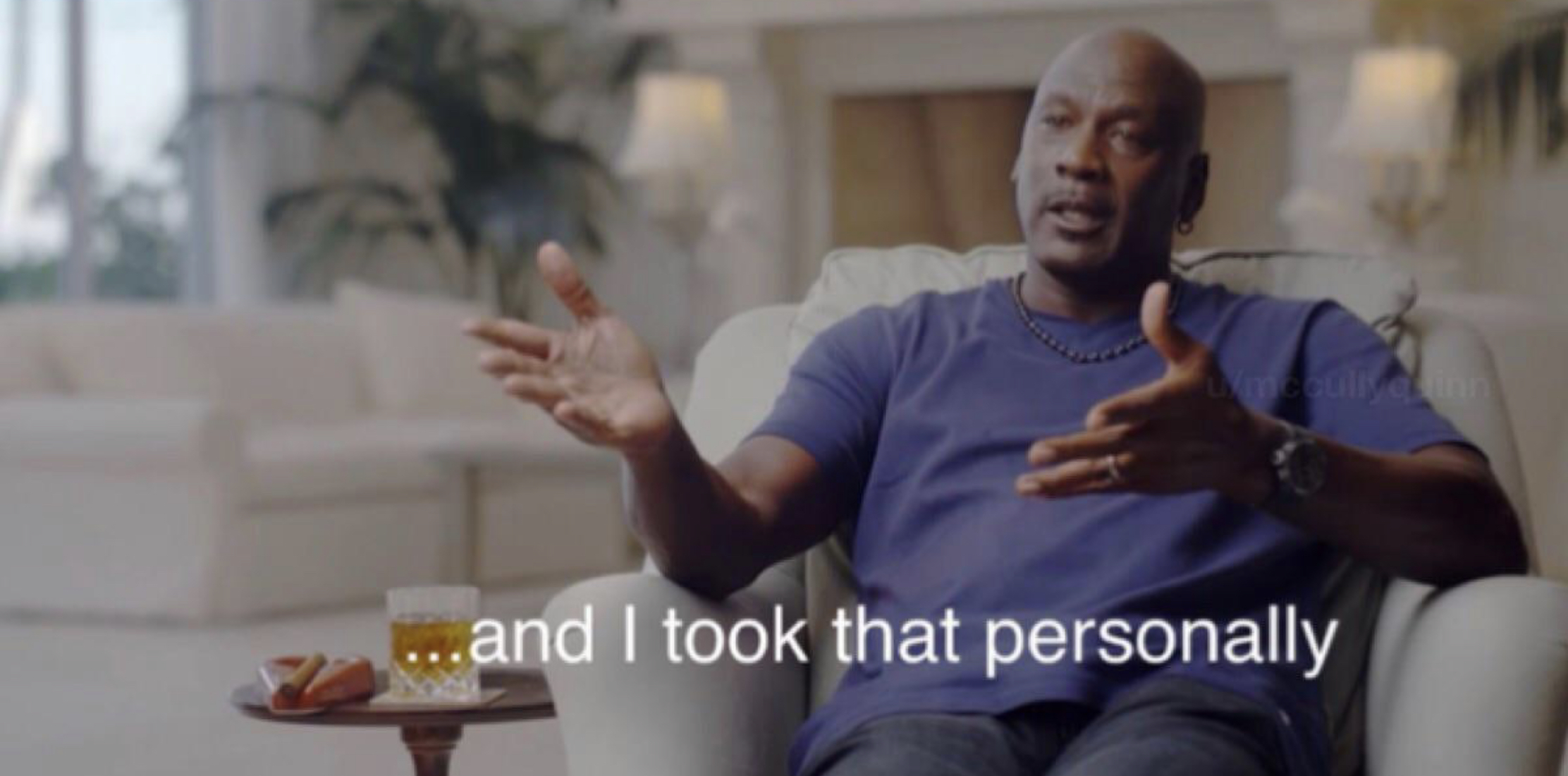

Michael Jordan didn't actually say the words "and I took that personally" during his Hall of Fame speech or any post-game press conference in the nineties. It’s a bit of a Mandela Effect situation, or rather, a masterpiece of documentary editing. The phrase exploded into the cultural lexicon during the 2020 release of The Last Dance, the ESPN/Netflix docuseries that charted the Chicago Bulls’ 1997-98 season. While Jordan uttered variations of the sentiment across ten episodes, the specific meme-worthy phrasing became a shorthand for a very specific, almost pathological level of drive. It’s about more than just a viral meme with a grainy photo of MJ in a suit; it’s a window into how the greatest winners in history manufacture motivation out of thin air.

Sometimes the "slight" wasn't even real.

Think about the LaBradford Smith incident. In March 1993, Smith, a relatively obscure player for the Washington Bullets, had the game of his life against Jordan, scoring 37 points. As the story goes, Smith supposedly told Jordan, "Nice game, Mike," as they left the court. Jordan was incensed. He promised to match Smith’s total in the first half of their next meeting. He nearly did, dropping 36 by halftime. Years later, Jordan admitted he completely made up the "Nice game, Mike" comment just to get himself fired up. He needed an enemy. If he didn't have one, he’d invent one. And I took that personally isn't just a funny caption for Twitter; it’s the blueprint for a psychological edge that turns a high-level athlete into a global icon.

The Anatomy of a Manufactured Grudge

Why does this matter? Because most of us wait for motivation to strike us like lightning. We wait for a promotion to be denied or a partner to hurt our feelings before we find that "extra gear." Jordan, and later Kobe Bryant with his "Mamba Mentality," flipped the script. They realized that the human brain performs better under a perceived threat. By taking everything personally—from Karl Malone winning the 1997 MVP to George Karl not saying hello at a restaurant—Jordan kept his cortisol and adrenaline levels at a competitive peak.

It’s exhausting. Most people can’t live like that.

💡 You might also like: El Salvador partido de hoy: Why La Selecta is at a Critical Turning Point

If you look at the 1992 Olympics, the "Dream Team" era, Jordan’s obsession with Jerry Krause (the Bulls GM) scouting Toni Kukoč is legendary. Jordan and Scottie Pippen didn't just want to beat Croatia; they wanted to destroy Kukoč because Krause liked him. They took a management decision and turned it into a personal vendetta. This is where the meme gets its teeth. It’s the realization that high performance often requires a villain. Even if that villain is just a guy trying to eat dinner at the same steakhouse as you.

Beyond the Meme: The Science of Spite

There’s actually some fascinating psychology behind why this works. Researchers often talk about "intrinsic" versus "extrinsic" motivation. Jordan is a weird hybrid. He had the intrinsic drive to be the best, but he used extrinsic "disrespect" as a fuel additive. When you tell yourself "and I took that personally," you are essentially engaging in a cognitive Reframing technique. You’re taking a neutral event—someone else's success—and turning it into a direct challenge to your status.

Spite is a powerful, if slightly toxic, fuel.

In a study published in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, researchers found that people who felt "belittled" actually performed better on creative and analytical tasks if they had a high "desire for power." For a guy like Jordan, power was everything. Every time B.J. Armstrong hit a shot and celebrated a little too hard, or Clyde Drexler was compared to him in the media, it wasn't just a sports debate. It was an existential threat.

📖 Related: Meaning of Grand Slam: Why We Use It for Tennis, Baseball, and Breakfast

When the Drive Becomes a Social Burden

We have to be honest here: living this way makes you kind of a jerk. The Last Dance didn't hide this. It showed teammates who were genuinely intimidated and, at times, miserable. The "and I took that personally" mindset doesn't have an off switch. It’s why MJ struggled with retirement. It’s why he was still taking shots at people during his 2009 Hall of Fame induction speech, a decade after his prime.

He was still keeping score.

You see this in business too. Look at Steve Jobs or Elon Musk. There is often a trail of broken professional relationships behind people who treat every market shift or competitor product as a personal insult. It’s effective for the bottom line, sure. Is it great for your blood pressure? Probably not. But in the context of 1990s NBA basketball, it was the difference between being a "great player" and being the "Greatest of All Time."

How to Use This Energy Without Burning Out

So, how do you actually apply this without becoming a social pariah? You have to learn to "rent" the mindset rather than "own" it. Jordan owned it. It was his permanent residence. For the rest of us, we can visit.

👉 See also: NFL Week 5 2025 Point Spreads: What Most People Get Wrong

- The "Silent" Vendetta: You don't actually have to tell the person you're mad at them. In fact, Jordan often didn't. He just played harder. If a coworker gets the lead on a project you wanted, don't complain. Use that "and I took that personally" energy to make your next presentation undeniable.

- Identify Your "Jerry Krause": Everyone has a person or an entity that represents the "doubters." Maybe it’s an old teacher, an ex, or just a competitor in your field. Use their success as a reminder of what you haven't achieved yet.

- The 24-Hour Rule: Jordan was a master of the immediate response. If he got embarrassed on a Tuesday, he was a nightmare on Wednesday. Don't let the "personal" grudge fester for years. Use the energy immediately to improve a skill or finish a task.

The Cultural Legacy of MJ’s Pettiness

We live in an era of "quiet quitting" and work-life balance. Jordan represents the antithesis of that. That’s why the meme resonates so much. It’s a nostalgic look back at a time when being "obsessed" wasn't a red flag, but a requirement for greatness. When we post that photo of MJ looking at the iPad with a glass of tequila nearby, we’re laughing at the absurdity of his pettiness, but we’re also secretly admiring it.

We all wish we cared that much about something.

The reality of the and I took that personally phenomenon is that it’s a defense mechanism. By making it personal, Jordan ensured he could never be bored. He could never be complacent. He was the defending champion for most of the nineties, a position that usually leads to "fat and happy" syndrome. By finding—or inventing—slights, he stayed lean and hungry.

Actionable Takeaways for Your Own "Personal" Growth

If you want to channel this energy, start by auditing your reactions to failure. Most people respond to a loss with excuses. "The refs were bad." "The market is down." "They had more funding."

Jordan’s genius was that he didn't make excuses; he made enemies.

- Stop Externalizing Failure: When something goes wrong, don't blame the system. Assume it happened because you weren't good enough yet. Take it personally.

- Find a Performance Trigger: Identify the specific comment or event that makes your blood boil. Instead of venting about it on social media, put that phone down and do twenty minutes of deep work or physical training.

- Gamify Your Grudges: Turn your professional goals into a series of head-to-head matchups. Even if the other person doesn't know they're in a race with you, you’ll find yourself moving faster.

- Know When to Fold It: Once the "game" is over, you have to be able to step back. Jordan’s biggest struggle was finding a way to exist in a world that wasn't a competition. Don't let your competitive fire burn down your house.

The meme will eventually fade, replaced by whatever the next Netflix sports doc produces. But the core truth remains: the people who win the most are usually the ones who found a way to make the struggle personal. They aren't just playing for a paycheck; they’re playing to prove someone wrong. Even if that "someone" never actually said a word.