You’re staring at your favorite Alocasia or maybe a row of backyard tomatoes, and something feels... off. The leaves look dusty. There’s a weird, dull bronze sheen where there used to be vibrant green. You suspect pests, so you pull up a high-resolution image of spider mites online. What you see is a terrifying, bulbous creature with eight legs and bristling hairs, looking like a monster from a low-budget sci-fi flick. But then you look back at your plant. Nothing. You see some tiny white specks that might be dust, or maybe some faint webbing in the crotch of a leaf.

That’s the problem with digital photography. It lies by being too clear.

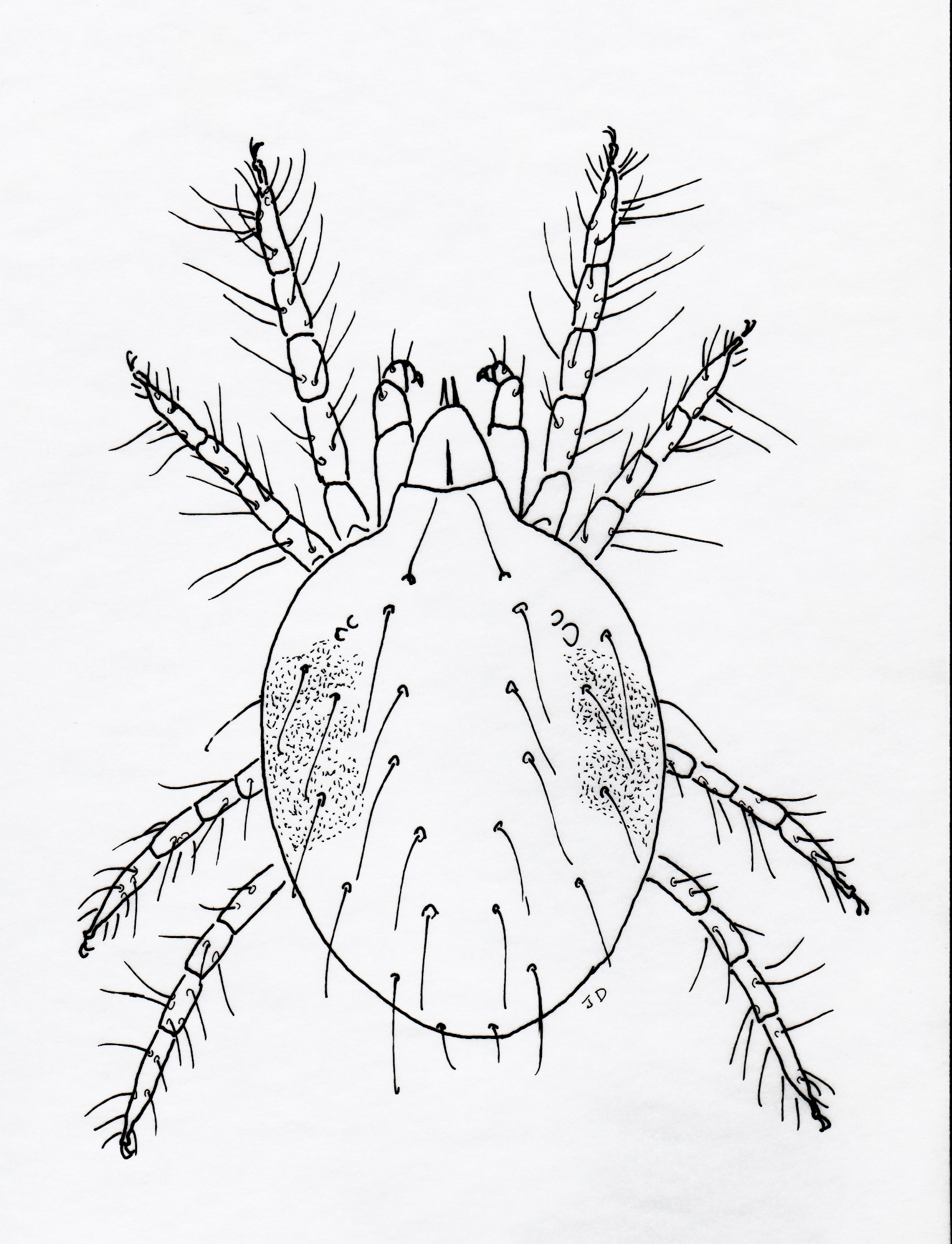

In the real world, identifying these arachnids—specifically the Tetranychus urticae or two-spotted spider mite—is an exercise in frustration because they are functionally invisible to the naked eye. Most people expect to see the "spiders," but what you’re actually looking for is the damage they leave behind. If you can see the actual mite without a macro lens or a 10x jeweler’s loupe, you either have eagle vision or a catastrophic infestation that might already be terminal for the plant.

The disconnect between a macro image of spider mites and reality

When you see a professional image of spider mites on a site like Nature or a university extension blog, you’re usually looking at a specimen under intense magnification. These creatures are roughly 1/50th of an inch long. That is roughly the size of a period at the end of a sentence. Because they are so small, your brain doesn't register them as "bugs." It registers them as texture.

I’ve spent years poking around greenhouses, and the biggest mistake hobbyists make is looking for movement. Spider mites aren't like fungus gnats; they don't fly around your face. They aren't like thrips that scuttle away when you flip a leaf. They sit. They suck. They ruin your day slowly.

The two-spotted variety is the most common one you'll find in a home setting. If you look at a high-quality photo, you’ll see two dark blotches on their backs. These aren't markings, actually. They are literally the mite's digestive organs visible through its translucent body. It’s kinda gross when you think about it—you’re looking at their last meal. In the winter, or when food is scarce, some species like the European red mite (Panonychus ulmi) turn a bright, alarming orange or red. This change, called diapause, is basically their version of hibernation. If your "image of spider mites" shows a sea of red dots, you're likely looking at a colony preparing for the long haul.

Why the webbing is a "too late" sign

We call them spider mites because of the silk. But honestly? If you see webbing that looks like a miniature Halloween decoration draped over your succulents, you’re in trouble.

✨ Don't miss: The Long Haired Russian Cat Explained: Why the Siberian is Basically a Living Legend

Mites produce silk to protect their eggs and to move from plant to plant. They catch air currents and "balloon" across your living room. It's ingenious. It's also a nightmare. A macro image of spider mites often highlights these silk strands because they catch the light beautifully in a studio setting. In your living room, that silk is a superhighway. By the time the webbing is visible to you without a flashlight, the population has likely exploded into the thousands.

Check the undersides. Always the undersides.

The "stippling" effect is your best diagnostic tool. Since spider mites have piercing-sucking mouthparts, they stab individual plant cells and drain the chlorophyll. This leaves behind tiny yellow or white dots. If you’re looking at a leaf and it looks like it was hit by a microscopic spray-paint can, that’s your sign. Forget the "bug" photos for a second and focus on the leaf's complexion.

The "White Paper Test" is better than any Google search

Stop squinting at the leaves. If you want to confirm what you saw in that image of spider mites is actually on your plant, do the paper test. It’s a classic for a reason.

- Take a plain sheet of white printer paper.

- Hold it underneath a suspect leaf.

- Tap the leaf sharply.

- Wait.

At first, you’ll just see dust and dirt. But wait five seconds. If some of those "dust" particles start moving slowly across the paper, congratulations: you have mites. If you smear one with your finger and it leaves a green or reddish streak, that’s the final confirmation. It’s much more reliable than trying to match a blurry smartphone photo to an expert-level entomology database.

Environmental triggers: Why they show up now

Spider mites love it hot and dry. This is why they are the kings of the "indoor winter" season. When we turn on our heaters, the humidity in our homes drops to desert levels. For a spider mite, this is a vacation. Under ideal conditions—around 80°F and low humidity—a female mite can go from an egg to a reproducing adult in about five to seven days.

🔗 Read more: Why Every Mom and Daughter Photo You Take Actually Matters

Think about that math. One female can lay hundreds of eggs. If each of those becomes an adult in a week, you aren't dealing with a linear growth curve. You're dealing with an explosion. This is why people think the mites appeared "overnight." They didn't. They were just waiting for the furnace to kick on so they could start their lineage.

Mistaken identity: Is it really a spider mite?

Not everything small and crawly is a villain. People often see a bright red, fast-moving mite on their concrete patio or a terracotta pot and panic. They find an image of spider mites online, see something red, and reach for the pesticides.

Usually, those fast-moving red guys are Clover Mites or predatory mites like Phytoseiulus persimilis. Predatory mites are the "good guys." They are slightly larger, have longer legs, and they move fast. Think of them like the wolves of the soil. If a mite is sprinting, it’s probably a hunter. If it’s huddling in a group on the bottom of a leaf and barely moving, it’s the pest you’re worried about.

There are also Broad Mites and Cyclamen Mites. You will almost never find a clear image of spider mites that covers these because they are truly microscopic. You can't see them with a magnifying glass. They don't cause stippling; they cause "distorted growth." If your new leaves are coming out twisted, rigid, or corkscrewed, you have these invisible hitchhikers.

Practical steps for eradication

If your plants match the grim reality of a spider mite infestation, put down the "all-purpose" bug spray. Most generic insecticides, especially those containing carbaryl, can actually make spider mite problems worse. Why? Because they kill the beneficial bugs that eat mites but don't touch the mites themselves. It’s like firing the police force and wondering why crime went up.

Immediate physical removal

Take the plant to the shower. Seriously. A strong stream of lukewarm water is the best first step. You want to physically blast the mites and their webs off the leaves. Pay special attention to the undersides and the "elbows" where the leaf meets the stem. Do this every three days for two weeks. You have to break the life cycle.

💡 You might also like: Sport watch water resist explained: why 50 meters doesn't mean you can dive

The soap and oil approach

Horticultural oils or insecticidal soaps are the gold standard here. They don't poison the mite; they suffocate it. You need to coat the entire plant until it's dripping. Since these oils don't kill the eggs, you must re-apply. If you miss even 5% of the population, they will be back in ten days.

Humidity is a weapon

Buy a humidifier. If you keep the ambient humidity above 50%, spider mites struggle to reproduce. They hate moisture. It gums up their breathing pores and slows their metabolism. Grouping your plants together also creates a micro-climate that acts as a natural deterrent.

Biological warfare

For those with large collections or greenhouses, buying predatory mites (like Neoseiulus californicus) is a game-changer. These tiny hunters will scour your plants, eating every spider mite they find, including the eggs. It's a "set it and forget it" solution, though it requires you to stop using chemical sprays entirely so you don't kill your expensive new allies.

Check your plants weekly. Use a flashlight. Look for the dullness before the webs appear. If you catch them when they look like a light dusting of flour rather than a scene from a horror movie, your plants will bounce back just fine.

Actionable Next Steps

- Audit your humidity: Use a cheap hygrometer to check the air around your plants. If it's under 40%, you're inviting an infestation.

- The Flashlight Test: Once a week, shine a bright light at an angle across the undersides of your leaves to catch the glint of early webbing.

- Isolate new arrivals: Never put a new plant in your main collection without a 14-day "quarantine." Mites are the ultimate hitchhikers from big-box stores.

- Clean the "dust": Use a damp microfiber cloth to wipe leaves regularly. It removes the dust that mites hide in and physically disrupts any early colonies.