Walk into any grandmother’s dining room in South Philly or a tiny village in Italy, and you’ll see it. It’s usually a faded lithograph or a dusty mirror print. That iconic image of Da Vinci's Last Supper is basically the most famous dinner party ever recorded, but honestly, most people are looking at a version that’s barely a shadow of the original. We’ve seen it on coffee mugs, mousepads, and even recreated with dogs playing poker. It’s everywhere.

But why?

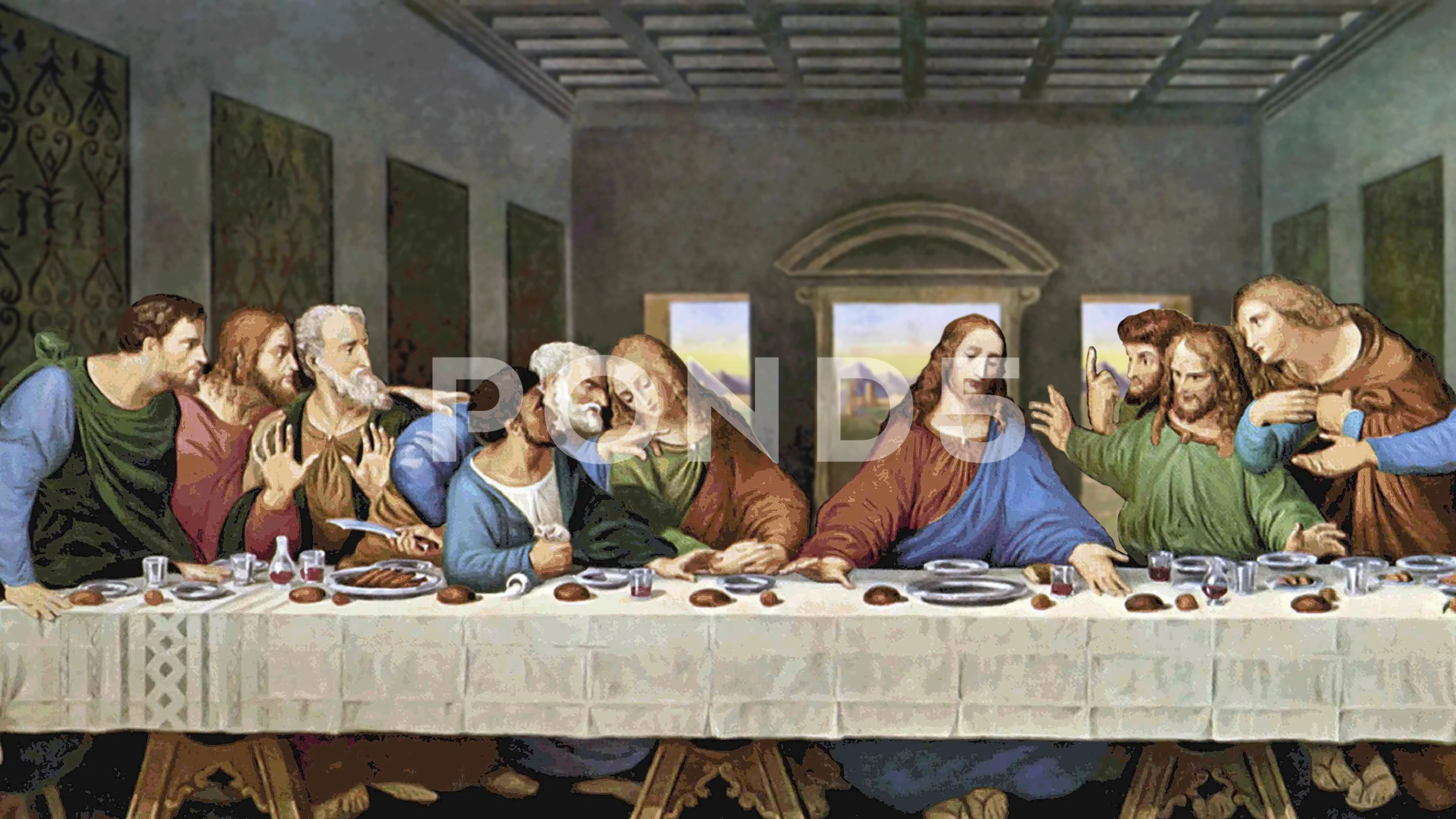

It’s just thirteen guys sitting on one side of a table. Weirdly, they’re all on the same side so the "camera" can see them. If you actually sat like that at a restaurant, the waiter would think you were insane. Yet, this specific composition by Leonardo da Vinci changed how humans perceive visual storytelling forever. It isn't just a religious painting; it's a high-stakes psychological thriller frozen in tempera and oil.

The disaster behind the masterpiece

Leonardo was a genius, but he was also a bit of a flake. He hated the traditional way of painting frescoes. Usually, you’d paint on wet plaster (buon fresco). You have to work fast before it dries. Leonardo didn't do "fast." He wanted to obsess over every shadow and chin. So, he decided to experiment on the wall of the Santa Maria delle Grazie convent in Milan. He used an experimental mix of oil and tempera on a dry wall.

It was a total flop.

Within years—not decades, years—the paint started flaking off. By the time he died, the image of Da Vinci's Last Supper was already deteriorating. It’s kind of tragic. The most famous mural in the world is essentially a slow-motion car crash of art supplies. Over the centuries, people tried to "fix" it, which usually meant making it worse. At one point, they even cut a door through the bottom of the painting, literally chopping off Jesus’ feet. Imagine being the guy who decided a doorway was more important than a Da Vinci.

What’s actually happening in the frame?

Most people think it’s just a group portrait. It’s not. Leonardo chose the exact moment of peak drama: "One of you will betray me."

✨ Don't miss: How to Sign Someone Up for Scientology: What Actually Happens and What You Need to Know

Look at the hands. Leonardo was obsessed with anatomy and "motions of the mind." He believed you could see a soul through a gesture. To the left of Jesus, you’ve got James the Greater throwing his arms out in total shock. Then there’s Philip, leaning in, pointing to his chest as if to say, "Is it me, Lord?" It’s chaotic. It’s loud. You can almost hear the chairs scraping against the floor.

And then there’s Judas.

In earlier versions of this scene by other artists, Judas was usually sat on the opposite side of the table, making him easy to spot. Leonardo thought that was too obvious. He put Judas in the mix, leaning back into shadow. He’s the only one whose face is in darkness. He’s also clutching a small bag—the thirty pieces of silver. If you look closely at a high-res image of Da Vinci's Last Supper, you'll see he’s knocked over a salt cellar. A bad omen, even back then.

The math of the mess

Leonardo was a math nerd. He used "linear perspective" to make the room feel like it was an extension of the actual dining hall where the monks ate. Everything leads to Jesus’ head. The windows, the ceiling panels, the tapestries on the wall—they all converge.

If you drew a line from every architectural element in the painting, they’d meet right at Jesus’ temple. It’s the ultimate "look here" trick. He also used the "Rule of Thirds" before it was a thing. The apostles are arranged in four groups of three. Three is a big number in Christian theology (the Trinity), and Leonardo leans into that. Jesus himself is shaped like a triangle.

It feels stable in the middle of a hurricane of human emotion.

🔗 Read more: Wire brush for cleaning: What most people get wrong about choosing the right bristles

Myths, Dan Brown, and the Mary Magdalene thing

We have to talk about the Da Vinci Code stuff. It’s the elephant in the room whenever someone looks at an image of Da Vinci's Last Supper. The theory is that the person to Jesus’ right (our left) isn't the Apostle John, but actually Mary Magdalene.

Art historians generally roll their eyes at this.

Back in the Renaissance, John was always depicted as "the beloved disciple"—which meant he was young, pale, and had long flowing hair. He was meant to look "effeminate" by modern standards because he represented purity. If you look at other paintings from the 1490s, John always looks like that. Also, if that’s Mary, where is John? Leonardo wasn't the type to just forget one of the main characters.

Why we can't stop looking

There’s a weird tension in the painting that never goes away. It’s the "uncanny valley" of the 15th century. Because the painting is so damaged, our brains try to fill in the gaps. We look for secrets. We look for hidden musical notes in the bread rolls (yes, people have actually tried to play the "music" of the Last Supper).

The 1999 restoration, led by Pinin Brambilla Barcilon, took twenty years. Twenty years to clean something Leonardo painted in three. They used microscopes to remove centuries of grime, glue, and bad touch-ups. What’s left is a ghost. But even as a ghost, it’s more powerful than 99% of the art created today.

It’s about the human reaction to a crisis.

💡 You might also like: Images of Thanksgiving Holiday: What Most People Get Wrong

Some people get angry. Some get sad. Some go into denial. Some (Judas) try to hide. When you see a high-quality image of Da Vinci's Last Supper today, you aren't just looking at a religious scene. You're looking at a map of human psychology.

How to actually appreciate the image today

If you want to go beyond just looking at a poster, you need to dig into the details. Here is how to actually "read" the painting if you’re looking at a high-resolution version online:

- Look at the hands first. Don't look at the faces. The hands tell the story of the reaction.

- Find the knife. Peter is holding a knife behind his back. It’s a bit of foreshadowing for when he cuts off the ear of the soldier in the Garden of Gethsemane later that night. It shows his impulsive, protective nature.

- Check out the feet. Or lack thereof. Since the door was cut into the wall, we lost the original perspective of the feet under the table, which Leonardo would have used to ground the figures.

- Observe the light. The light in the painting actually matches the light from the real windows in the room where it was painted. Leonardo wanted the monks to feel like Jesus was actually sitting there with them in Milan.

Practical takeaways for the art-curious

Don't just settle for a cheap, saturated print. If you're looking for an image of Da Vinci's Last Supper to hang up or study, find a "pre-restoration" and a "post-restoration" comparison. It’s wild to see how much of the original color was lost.

- Seek out the Royal Academy copy: There is a full-scale copy painted by Leonardo's pupils (Giampietrino and Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio) on canvas. Because it was painted on canvas and not a damp wall, the colors are vivid. It’s the best way to see what Leonardo actually intended the painting to look like before it started rotting.

- Visit virtually: The Santa Maria delle Grazie has strict limits on visitors (you get 15 minutes, tops). But you can find ultra-high-definition gigapixel images online that let you zoom in closer than you ever could in person.

- Context is everything: Remember that this was painted in a "refectory"—a dining hall. The monks would eat in silence while looking at this image of the most famous meal in history. It was designed to be lived with, not just stared at in a museum.

The power of the work doesn't come from its "perfection." It comes from its fragility. The fact that it still exists at all, after bombings in WWII (the room was hit, but the wall with the painting survived by a miracle of sandbagging) and 500 years of humidity, is insane. It’s a survivor.

When you look at that image, you're seeing the intersection of failed chemistry and absolute genius. That's why we’re still talking about it. That's why it still feels alive, even if the paint is barely hanging on.

Go find a high-res version of the Giampietrino copy. Compare it to the original in Milan. You’ll notice things—like the salt, the knife, and the specific tension in Peter’s wrist—that you never saw in the grainy versions from your childhood. It changes the whole experience from a "religious icon" to a masterpiece of human drama. Look at the feet in the copy; they reveal the groundedness Leonardo originally intended. Study the expressions again, but this time, imagine the noise of the room. That’s the real way to see it.