Money has a way of disappearing if you aren't looking closely. Most people check their bank balance and think they’re seeing the whole story, but they’re just seeing a snapshot. If you really want to know where you're headed, you need to understand the math of the future. Specifically, using an fv calculator with contributions is the difference between guessing and actually knowing.

Compounding is weird. It doesn't feel real until you see the numbers move.

Basically, the "Future Value" (FV) is just a fancy way of asking: "What will this pile of cash be worth in ten years if I don't touch it and keep adding to it?" If you just drop $10,000 into an index fund and walk away, that’s one thing. But life doesn't usually work like that. You get paid every two weeks. You save a little here and there. That’s where the "contributions" part of the equation changes everything.

The Math Behind the FV Calculator with Contributions

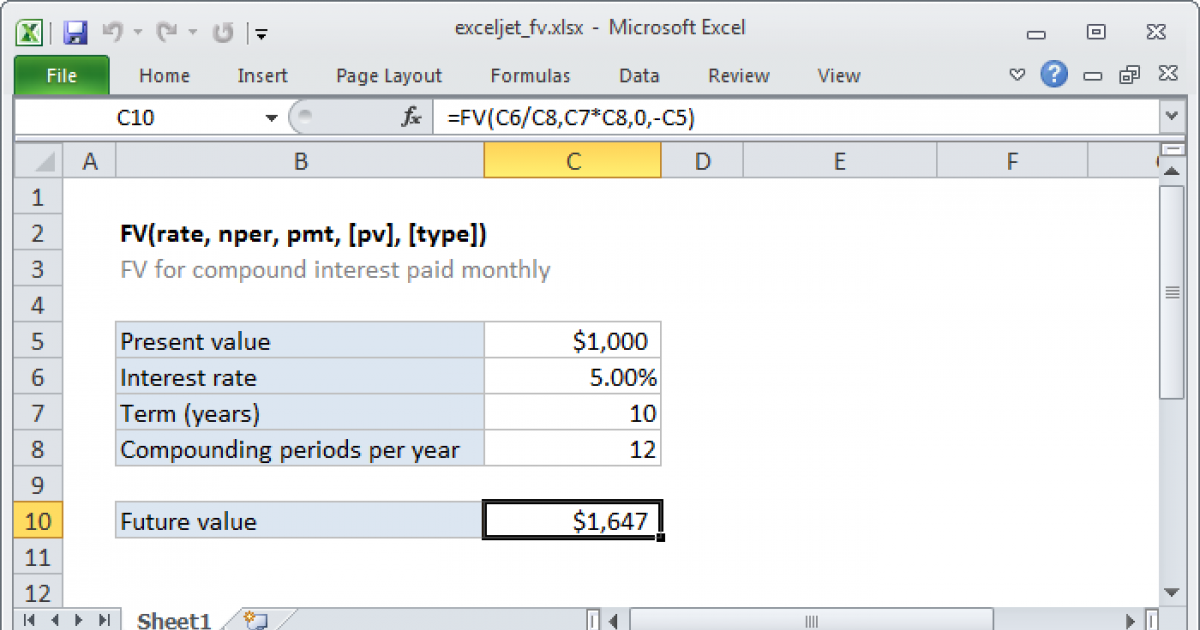

Let's get technical for a second, but not too boring. The standard formula for future value is $FV = PV(1 + r)^n$. That works if you have a lump sum. But when you add monthly or yearly payments, the formula gets way more aggressive. It looks like this:

$$FV = PV(1 + i)^n + PMT \times \frac{(1 + i)^n - 1}{i}$$

In this scenario, $PV$ is your starting amount, $i$ is your interest rate per period, $n$ is the number of periods, and $PMT$ is your recurring contribution.

Most people fail to account for the second half of that equation. They focus on the $PV$. They worry about whether they have enough to "start" investing. Honestly? The $PMT$—your regular contribution—is usually the real hero of the story for the first 15 years of any portfolio. It’s the engine. Without it, the car just sits in the driveway looking pretty.

✨ Don't miss: Starting Pay for Target: What Most People Get Wrong

Why Your "Estimated" Return is Probably Wrong

We see 7% or 10% thrown around a lot because of the S&P 500's historical average. But inflation is a thief. If you’re using an fv calculator with contributions and you aren't adjusting for a 2% or 3% inflation rate, you’re looking at "nominal" wealth, not "real" purchasing power.

You might end up with a million dollars, but if a loaf of bread costs twenty bucks by then, did you really win?

Experts like Jeremy Siegel, author of Stocks for the Long Run, often point out that while nominal returns look great on a chart, the real return (after inflation) is what dictates your lifestyle. When you're plugging numbers into a calculator, try running a "pessimistic" scenario. Use 5% instead of 10%. If the plan still works at 5%, you’re in a great spot. If it requires 12% to succeed, you aren't investing; you're gambling on a miracle.

The Secret Power of Frequency

Does it matter if you contribute $500 once a month or $6,000 once a year?

Mathematically, yes.

Because of how compounding periods work, the earlier the money gets into the account, the more "time" it has to capture growth. If you put money in at the start of the month, it’s working for you for 30 days longer than if you waited until the end. Over thirty years, these tiny fragments of time add up to thousands of dollars in "free" gains. It's kinda wild when you see the breakdown.

🔗 Read more: Why the Old Spice Deodorant Advert Still Wins Over a Decade Later

Most high-end tools allow you to toggle between "beginning of period" and "end of period" contributions. Always choose the beginning if you can swing it. It’s a small tweak that pays off massively in the long run.

Real World Example: The Coffee Myth vs. Reality

You’ve heard the tired cliché: "Stop buying lattes and you’ll be a millionaire." It’s mostly nonsense, but there’s a grain of truth hidden in the math.

Let's say a daily coffee habit is $6. That’s roughly $180 a month.

If you take that $180 and put it into an investment account earning 8% annually:

- In 10 years, you have about $32,000.

- In 20 years, you have about $100,000.

- In 30 years, you’re looking at nearly $260,000.

Is $260,000 enough to retire? No. But is it better than a pile of empty paper cups? Obviously. The fv calculator with contributions shows that small, annoying, repetitive amounts of money are actually quite powerful if you give them enough time to sit in a corner and grow.

Common Mistakes People Make with FV Calculations

People are optimistic by nature when it comes to their own money. They think they’ll never have a "bad" year.

- Ignoring Taxes: Unless you are using a Roth IRA or a tax-advantaged 401k, Uncle Sam is going to take a bite out of your gains. If your calculator says you'll have $500,000, and you’re in a 20% capital gains bracket, you actually have $400,000. Huge difference.

- The "Flat Line" Fallacy: Markets don't go up by exactly 8% every single year. They go up 20%, down 10%, flat for two years, then up 15%. This is called "sequence of returns risk." If you hit a string of bad years right when you start, your future value will look very different than if those bad years happened at the end.

- Inconsistent Contributions: Life happens. Your car breaks. You lose a job. Most people stop contributing during the "down" years, which is actually the worst time to stop because assets are cheap.

Why You Should Run Your Numbers Every Six Months

The world changes. Interest rates go up (as we've seen recently with the Fed’s pivots), and your goals will shift. Maybe you wanted to retire in Florida, but now you want to buy a farm in Vermont.

💡 You might also like: Palantir Alex Karp Stock Sale: Why the CEO is Actually Selling Now

Using an fv calculator with contributions isn't a "set it and forget it" task. It’s a diagnostic tool.

If you find that your projected future value is falling short of your goal, you have three levers to pull. You can contribute more money. You can take more risk to try for a higher return (which is dangerous). Or, you can push your timeline back.

Most people choose the fourth option: they ignore it and hope for the best. Don't do that.

Actionable Steps to Take Right Now

Stop guessing. If you want to actually hit your financial goals, you need a process that is grounded in reality, not hope.

- Audit your current contributions. Look at your 401k, your IRA, and your brokerage accounts. What is the actual monthly dollar amount going in?

- Run a "Conservative" FV Projection. Use a 6% return rate. If you’re happy with that number, you’re on the right track. If that number scares you, you need to increase your monthly contribution immediately.

- Automate the PMT. The "contribution" part of the future value formula only works if it actually happens. Set up an auto-transfer from your bank so you don't have to be "brave" enough to invest every month.

- Factor in the Fees. If you’re paying a 1% management fee to an advisor, subtract that from your expected return. An 8% return becomes a 7% return. Over 30 years, that 1% fee can cost you hundreds of thousands of dollars.

The math doesn't lie, even if our brains try to. Use the tools available to see the truth about your trajectory. Your future self will either thank you or wonder why you didn't spend five minutes with a calculator today.