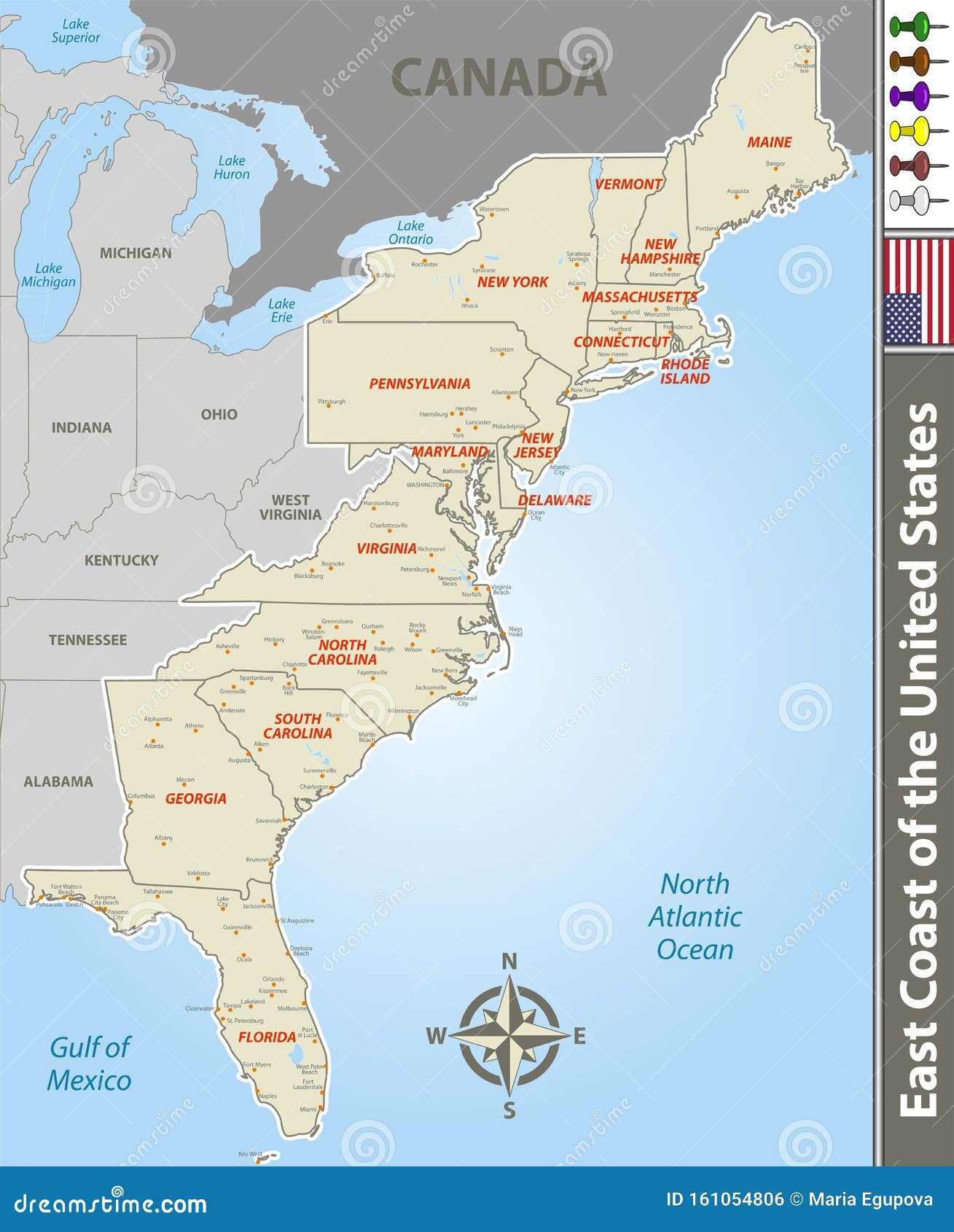

If you look at an east coast of the us map, you probably see a straight shot from Maine down to Florida. It looks simple. Just a long line of states hugging the Atlantic Ocean, right? Actually, it's a mess. A beautiful, jagged, culturally fragmented mess that stretches over 2,000 miles. Most people think the "East Coast" is just the I-95 corridor. They're wrong. Honestly, the way we map this region dictates everything from how we pay for tolls to where we hide from hurricanes.

Mapping the Atlantic seaboard isn't just about drawing lines. It’s about understanding the "Fall Line." This is a geological boundary where the hard rocks of the interior meet the softer coastal plain. If you look at a topographic east coast of the us map, you’ll notice cities like Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Richmond all sit right on this line. Why? Because back in the day, boats couldn't go any further inland than the first set of waterfalls.

That’s history written in the dirt.

The Three Hidden Zones of the East Coast

The map is basically split into three distinct personalities. You have the North Atlantic, the Mid-Atlantic, and the South Atlantic. They don't even feel like the same country half the time.

In the North, specifically Maine and New Hampshire, the map is a disaster of granite. Glaciers literally chewed up the coastline 10,000 years ago. This created "fjards"—which are like fjords but shallower. If you tried to walk the actual shoreline of Maine, you’d be walking for over 3,000 miles even though the state is only 220 miles long as the crow flies. That’s the power of a jagged map.

Then you hit the Mid-Atlantic. This is the "Megalopolis." Geographer Jean Gottmann coined that term in 1961 to describe the continuous urban sprawl from Boston to Washington, D.C. On a night-time satellite map, this area glows like a single, massive neon organism. It’s dense. It’s loud. It’s where the infrastructure is most stressed.

Down South, the map flattens out. The "Coastal Plain" takes over. You get the Outer Banks of North Carolina—a thin ribbon of sand that’s basically a graveyard for ships. These barrier islands are constantly moving. A map of the East Coast from 1920 looks nothing like one from 2026 because the ocean literally eats the land and spits it back out somewhere else.

👉 See also: Flights from San Diego to New Jersey: What Most People Get Wrong

The Problem with the "Eastern Seaboard" Definition

People argue about what counts. Does Vermont count? It’s in New England, but it’s landlocked. Most geographers say no. If you can’t smell salt water, you aren't on the East Coast.

The U.S. Census Bureau and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) have different ways of slicing the pie. NOAA focuses on the "Coastal Zone Management Act" boundaries. This includes the 14 states that touch the Atlantic: Maine, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania (via the Delaware Estuary), Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida.

Wait, Pennsylvania?

Yeah. Philadelphia is a deep-water port. Even though it's miles from the open ocean, it functions as a coastal hub. This is why a standard east coast of the us map can be deceptive if it only highlights the states with "beachfront" property.

Navigating the I-95 Mental Map

For most travelers, the map is just a blue line on a GPS labeled I-95. This highway is the spine of the coast. But it’s a brutal way to see the country. If you stay on 95, you miss the real geography. You miss the Chesapeake Bay, which is the largest estuary in the United States.

The Chesapeake is a massive indentation in the map that creates a logistical nightmare. To get from Norfolk, Virginia, to the Delmarva Peninsula, you have to use the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel. It’s 17 miles long. It goes underwater twice so Navy ships can pass over your head. If you aren't looking at a detailed map, you’ll completely miss how much water dictates travel in the Mid-Atlantic.

✨ Don't miss: Woman on a Plane: What the Viral Trends and Real Travel Stats Actually Tell Us

Let's Talk About the "Aches"

The East Coast has two major "Aches"—the Appalachians and the Atlantic.

The mountains run parallel to the coast, creating a corridor. This geographic "trough" is why the East Coast is so prone to Nor'easters. Cold air gets trapped between the mountains and the warm Gulf Stream water. The map isn't just a guide for driving; it's a blueprint for some of the wildest weather on earth.

- The Gulf Stream: This "river in the ocean" hugs the coast up to Cape Hatteras before veering toward Europe.

- The Continental Shelf: It’s much wider in the North (near the Georges Bank) than in the South. This is why the water in Maine is freezing and the water in Florida is like a bathtub.

- The Tidewater Region: This is where the rivers are affected by the tides. In Virginia and North Carolina, you can be 50 miles inland and still see the water level rise and fall twice a day.

Misconceptions About Distance

Distance on an east coast of the us map is a lie.

Driving from the top of Maine to the bottom of Florida is roughly 1,900 miles. That’s about 30 hours of driving. But that doesn't account for the "Jersey Turn-Pike Effect." The density of the map between New York City and Washington D.C. means that 100 miles can take three hours.

In the West, 100 miles is a blink. In the East, 100 miles can take you through three different states, four different accents, and six different types of pizza.

The scale is just different. Rhode Island is the smallest state on the map. You can drive across it in 45 minutes. Contrast that with Florida, which takes a full day just to get from the Georgia border to Key West. The map shrinks and expands based on the population density.

🔗 Read more: Where to Actually See a Space Shuttle: Your Air and Space Museum Reality Check

Why the Map is Changing

We have to talk about sea-level rise. It’s not a "maybe" thing anymore.

If you look at high-resolution topographical maps of the East Coast, places like the Jersey Shore, the Norfolk Naval Base, and the entire city of Miami are at extreme risk. The map is literally being redrawn. In the next 50 years, some of the barrier islands we see on today's maps will likely be submerged shoals.

South Carolina's "Lowcountry" is called that for a reason. It’s barely above sea level. When a hurricane hits, the map becomes a series of islands. This is why modern digital maps now include "storm surge" layers. It's no longer enough to know where the roads are; you have to know where the water will be.

How to Actually Use an East Coast Map for Travel

Don't just use Google Maps. It will always put you on the fastest, most boring route.

If you want to see the East Coast, you need to look for the "Blue Highways." These are the smaller, older roads like US-1. US-1 predates the Interstates. It runs from Fort Kent, Maine, all the way to Key West. If I-95 is the spine, US-1 is the skin. It goes through the heart of the old downtowns.

- Look for the gaps. The map between Charleston and Savannah is a maze of islands and marshes. This is the Gullah-Geechee Heritage Corridor. It’s one of the most culturally significant areas in the U.S., but it looks like "nothing" on a standard highway map.

- Follow the lighthouses. From Quoddy Head in Maine to the Ponce de Leon Inlet in Florida, lighthouses mark the dangerous bits of the map. They are the original GPS.

- Check the ferries. In North Carolina and New England, the map isn't connected by bridges. You have to time your life by the ferry schedule. The Cape May-Lewes Ferry, for example, saves you a massive drive around the Delaware Bay.

The East Coast is a dense, layered experience. It’s not just a list of states. It’s a collision of the Atlantic Ocean and the Appalachian foothills.

Moving Forward

When you're planning your next move or trip, grab a physical map. Or at least zoom in until you can see the inlets and the state parks. Stop looking at the East Coast as a transit corridor and start looking at it as a collection of estuaries, mountain gaps, and historical bottlenecks.

Next Steps for Your Trip:

Download the NOAA Sea Level Rise Viewer to see how the coastline is projected to change in the areas you’re visiting. If you’re driving, avoid I-95 between 3:00 PM and 7:00 PM in the Mid-Atlantic—the map doesn't show traffic, but the locals know that "red" on the GPS in northern Virginia is a permanent state of being. Stick to the coastal routes like Highway A1A in Florida or Route 1 in Maine for the best views.