You're sitting in a coffee shop on Commercial Street, watching the ferries tug away from the pier, and suddenly the floor shuddering isn't just a heavy truck passing by. Most people think of Maine as a geological vault—solid, ancient granite that doesn't budge. But an earthquake in Portland Maine isn't some freak "once in a billion years" event. It’s a part of the landscape’s history that we've mostly just forgotten because our human timelines are so short compared to the rocks beneath our feet.

Maine sits on the North American Plate. We aren't near a plate boundary like California, so we don't get those massive, terrifying "Big One" scenarios. However, the ground here is actually under a lot of stress. Imagine a giant sponge that was squashed under a heavy weight for a long time and is now slowly, painfully popping back into its original shape. That’s basically what’s happening with the crust in New England. During the last ice age, massive glaciers—miles thick—sat on top of Maine. They were heavy. When they melted about 12,000 years ago, the land started rising back up, a process geologists call post-glacial rebound.

This creates internal pressure. Sometimes, that pressure finds a weak spot in the old, buried fault lines that crisscross the state.

The Ghost Faults of Casco Bay

When you look at the jagged coastline of Casco Bay, you’re looking at the scars of ancient tectonic battles. There are faults all over the place. Most of them are "inactive" by standard definitions, but "inactive" doesn't mean "dead." It just means they haven't moved in a way we’ve recorded recently. In 2012, a 4.0 magnitude quake centered near Hollis sent a literal shockwave through Portland. People felt it as far away as Connecticut. It wasn't a catastrophe, but it was a wake-up call.

It felt like a bomb went off. Or a train hitting the house.

The geology of Portland makes the shaking feel different depending on where you are. If you’re up on Munjoy Hill or the Western Promenade, you’re likely sitting on bedrock or very dense glacial till. The shaking there might be sharp but short. But if you’re down in the "Back Cove" area or the Bayside neighborhood, you’re standing on what used to be tidal flats and filled land. That stuff is basically jelly when an earthquake hits. It amplifies the waves.

👉 See also: What Really Happened With the Women's Orchestra of Auschwitz

The Maine Geological Survey (MGS) has been tracking these "intraplate" quakes for decades. They’ll tell you that while we don't have a San Andreas, we do have the Norumbega Fault Zone. It's a massive system of faults that runs right through the heart of the state. It's old—formed hundreds of millions of years ago—but it still settles.

Why We Should Actually Care

It's easy to joke about a 2.0 or 3.0 quake being "just a vibration." But Portland has a specific vulnerability: old brick.

Walk around the Old Port. It’s beautiful, right? All that historic red brick and masonry from the late 1800s. The problem is that unreinforced masonry is the worst possible material to be in during an earthquake. Brick doesn't flex. It snaps. While a modern steel-frame building in Downtown Portland might sway and creak, an old warehouse on Wharf Street could shed its facade onto the sidewalk in a moderate quake.

We saw this in the 1755 Cape Ann earthquake. That was centered off the coast of Massachusetts but it hammered the entire New England coast. It was likely a magnitude 6.0 to 6.3. If that happened today, the economic damage to a city like Portland would be staggering. We aren't built for lateral movement. Most of our houses are "stick-built" wood frames, which actually do okay because wood is flexible, but the chimneys? Those are coming down.

Breaking Down the Myths

People always say, "Maine doesn't have earthquakes." Honestly, that's just statistically wrong. Maine has several dozen recorded earthquakes every single year. Most are so small you'd only notice if you were sitting perfectly still in a silent room, but they happen.

✨ Don't miss: How Much Did Trump Add to the National Debt Explained (Simply)

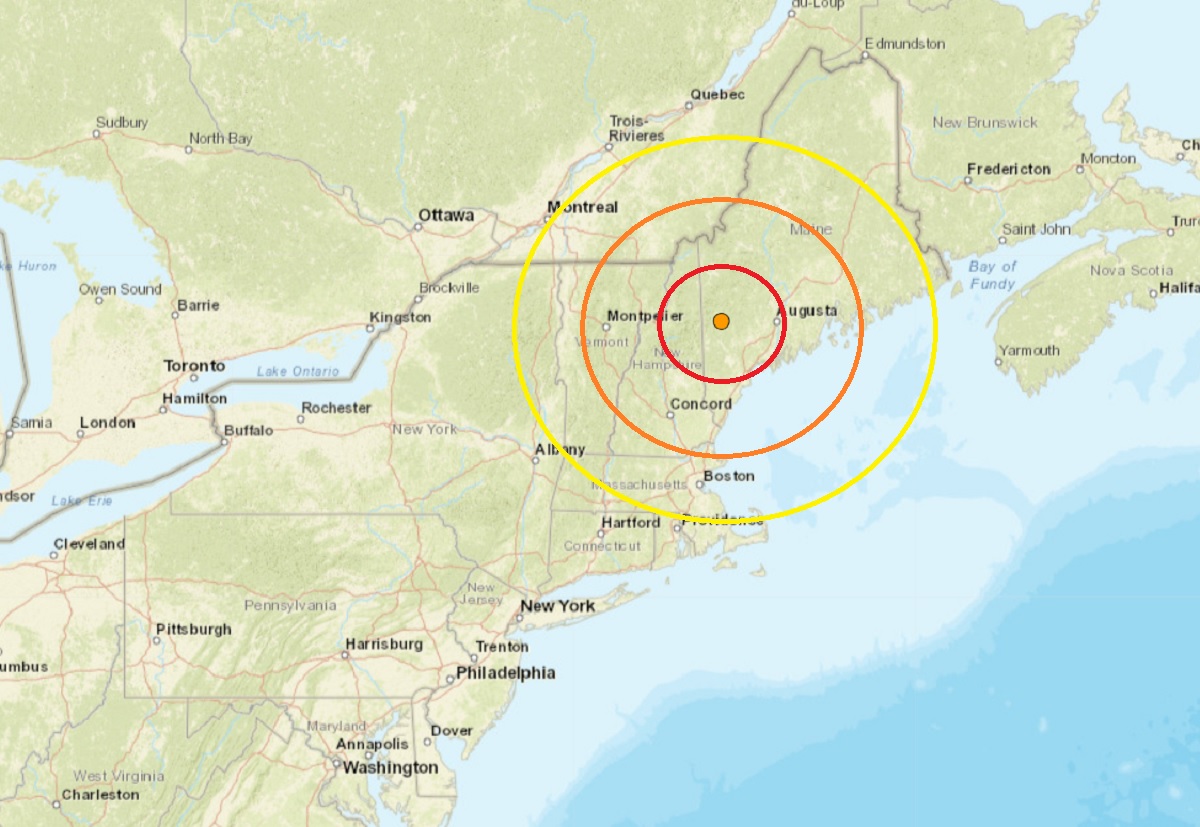

Another big misconception is that earthquakes here are shallow and don't travel far. It’s actually the opposite. In California, the crust is broken up and "warm" from all the tectonic activity. That absorbs the energy of a quake, kind of like a shock absorber. In New England, the crust is cold, hard, and continuous. When a fault slips near Portland, that energy rings through the rock like a bell. A 4.0 in Maine is felt over a much wider area than a 4.0 in Los Angeles.

Think about the 1904 earthquake. It was centered near Eastport but it shook the entire state of Maine and parts of New Brunswick. It was a massive event that would cause chaos in today's interconnected world of fiber-optic cables and gas lines.

What the Experts Say

Dr. Henry Berry at the Maine Geological Survey has spent years looking at these patterns. The consensus isn't that we are "due" for a big one—earthquakes don't really work on a schedule like that—but rather that the probability is non-zero. The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) includes Southern Maine in a zone of "moderate" seismic risk.

It’s not just the ground shaking, either. Because Portland is a coastal city, there is always the distant, albeit tiny, possibility of a tsunamigenic event if a massive landslide occurred on the continental shelf. We actually have evidence of "paleotsunamis" in the North Atlantic. It sounds like a movie plot, but the geological record doesn't lie.

Practical Steps for Portland Residents

So, what do you actually do? You don't need to build a bunker in the North Woods. But a little bit of common sense goes a long way when you live in a region that's technically seismically active.

🔗 Read more: The Galveston Hurricane 1900 Orphanage Story Is More Tragic Than You Realized

Secure the heavy stuff. If you live in one of those gorgeous high-ceilinged apartments in the West End, check your bookshelves. Are they bolted to the wall? If an earthquake in Portland Maine hits at 2:00 AM, you don't want a heavy mahogany dresser tipping over.

Learn where your shut-offs are. This is the big one. In an earthquake, it’s rarely the shaking that gets you; it’s the fires afterward. Gas lines in old Portland buildings are often rigid. If the building shifts, the pipe cracks. You need to know exactly how to turn off your gas and water in under sixty seconds.

Retrofit the old masonry. If you own a historic building, talk to a structural engineer about "retrofitting." It’s basically just adding some steel reinforcements so the walls stay attached to the floors when things start to wobble.

The "Drop, Cover, and Hold On" rule. Forget the doorway myth. Doorways in modern or even 19th-century homes aren't stronger than the rest of the house. Get under a sturdy table. Protect your head. Wait for the rolling to stop.

Maine is one of the safest places to live in terms of natural disasters, but that safety leads to complacency. We prepare for blizzards and Nor'easters because we see them coming on the radar. Earthquakes give no warning. They are the ultimate "blindside" event.

The best time to prepare for the next shake was yesterday. The second best time is right now. Check your insurance policy too—most standard homeowners' insurance in Maine specifically excludes earthquake damage. It’s usually a separate rider and, because the risk is perceived as low, it’s often surprisingly cheap.

Next Steps for Safety:

- Walk through your home and identify "top-heavy" furniture that needs anchoring.

- Locate your main gas shut-off valve and ensure you have the right wrench nearby.

- Verify if your insurance policy covers seismic events; if not, call your agent for a quote on an earthquake rider.

- Create a basic emergency kit with three days of water and non-perishable food, as a quake could disrupt local infrastructure for longer than a typical snowstorm.