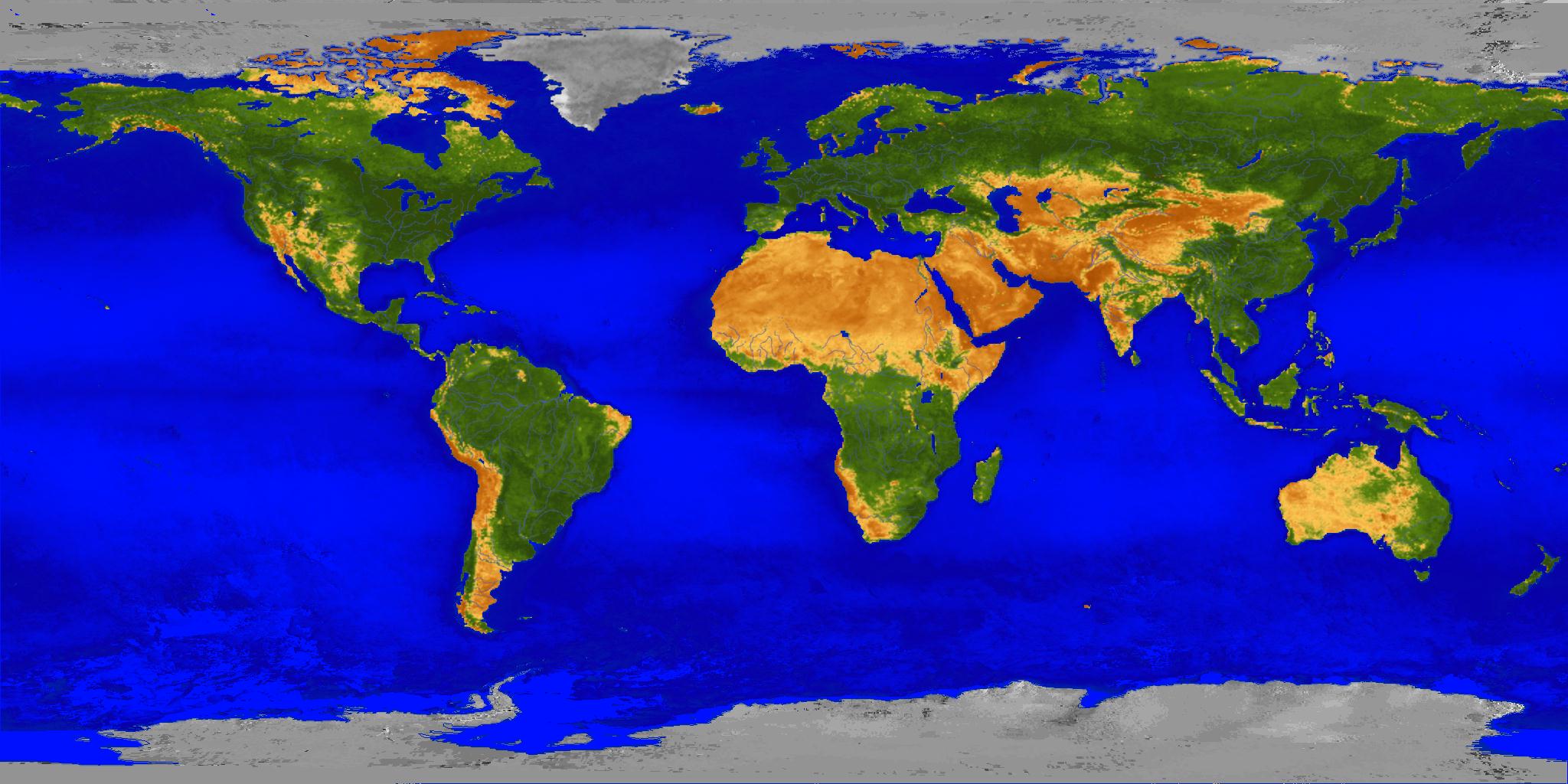

You’re looking at a lie. Every time you open Google Maps or pull a dusty rolled-up earth map out of a classroom closet, you’re seeing a version of reality that’s mathematically impossible. It’s kinda wild when you think about it. You can't flatten a sphere onto a piece of paper without tearing the image or stretching it into oblivion. Imagine trying to gift-wrap a bowling ball with a single sheet of paper without making a single wrinkle. You can’t.

So, we compromise.

We’ve been compromising for centuries. The most famous version, the Mercator projection, was designed in 1569. It wasn't made for classroom walls or to show how big countries are. It was a tool for sailors. Gerardus Mercator needed a way for navigators to draw a straight line between two points and actually get there. To do that, he stretched the poles.

This is why Greenland looks like it’s the size of Africa on a standard earth map. In reality? Africa is fourteen times larger. You could fit Greenland, the United States, China, India, and most of Europe inside Africa’s borders. But because we see these maps every day, our brains get hardwired to believe in a geography that doesn't exist.

The Digital Evolution of the Earth Map

Fast forward to 2026. We don't use paper much anymore. We use pixels.

✨ Don't miss: I See 50 in the Sky: Why This Satellite Phenomenon Still Surprises Us

The way we interact with an earth map today is fundamentally different because of "slippy maps." This is the technical term for what happens when you drag your finger across a smartphone screen and the world follows. It’s seamless. It’s fast. But the tech behind it is actually quite old-school. Most web maps still use a variation called Web Mercator. Why? Because it preserves angles. If you’re looking at a street corner in New York, it should look like a 90-degree angle. If the map distorted those angles to show the "true" size of the continent, every city street would look like a funhouse mirror.

Technology has bridged the gap between the flat map and the round reality. When you zoom out far enough on Google Maps now, the interface actually snaps into a 3D globe. This was a massive shift in 2018. Before that, the world stayed flat no matter how far you scrolled. Now, the earth map is a dynamic, living thing.

It’s fed by data. Lots of it.

We have the Landsat program, a joint effort between NASA and the USGS, which has been capturing imagery since the 70s. Then there’s the European Space Agency’s Sentinel satellites. These things are orbiting us right now, snapping photos that allow us to see the world changing in real-time. We can watch deforestation in the Amazon or the retreat of glaciers in Antarctica with a resolution that would have seemed like science fiction twenty years ago.

Why Accuracy is a Moving Target

Geodesy is the science of measuring the Earth’s shape. Here’s a secret: the Earth isn't a perfect sphere. It’s an oblate spheroid. It’s a bit pudgy around the middle.

Because the planet is lumpy, we need "datums." Think of a datum as a starting point. The World Geodetic System (WGS 84) is the standard used by GPS. When your phone tells you where you are on an earth map, it's calculating your position relative to this invisible mathematical model of the Earth's center of mass.

But even the land moves.

Plate tectonics means that continents shift a few centimeters every year. In Australia, the continent moves so fast—about 7 centimeters a year—that they’ve had to update their official coordinates multiple times just so self-driving cars and GPS systems don't get confused. If the earth map doesn't update, your "accurate" pin might be sitting in the middle of a bush instead of the driveway.

Beyond Just Navigation

We used to use maps to find our way to the grocery store. Now, we use them to solve global crises.

Take the "Global Forest Watch" platform. It uses satellite-based earth map data to track illegal logging. Or look at how we track pandemics. During the early 2020s, the Johns Hopkins dashboard became the most-watched map in history. It showed us that maps aren't just about land; they're about people, movement, and risk.

💡 You might also like: eufy L60 Robot Vacuum with Self Empty Station: What Most People Get Wrong

There's also the "OpenStreetMap" (OSM) project. It’s basically the Wikipedia of maps. Thousands of volunteers around the world manually trace roads, buildings, and rivers. In many parts of the developing world, commercial map providers don't have great data. But because of OSM, an earth map of a remote village in South Sudan can be just as detailed as a map of downtown London. This is literally life-saving during natural disasters when rescue workers need to know which bridges are washed out or where the nearest well is located.

The Psychology of the Map

Maps are power. Whoever draws the lines defines the world.

Think about "South-up" maps. There is no physical reason why North has to be at the top of an earth map. Space has no "up." We put North at the top because of European cartographic traditions. When you flip the map so South is at the top, Australia looks like it's looming over the rest of the world. It changes your perspective on geopolitical importance instantly.

Psychologists have found that people often perceive "up" as "better" or "richer." By consistently seeing the Global South at the bottom of the earth map, we subconsciously reinforce social hierarchies.

Then there's the Gall-Peters projection. This one looks weird. The continents look stretched vertically, like they've been through a pasta maker. But it’s an "equal-area" map. It shows the true relative sizes of landmasses. While it’s terrible for navigation, it’s arguably much more "honest" for educational purposes. Some school districts, like Boston Public Schools, have actually switched to Gall-Peters to give students a more accurate sense of the world’s proportions.

Visualizing the Invisible

An earth map today can show things the human eye can't see. We have maps of light pollution. We have maps of underwater internet cables—the literal nervous system of our planet. We have heat maps showing where the urban heat island effect is making cities unbearable during summer.

The "Earth Wind Map" is a gorgeous example of this. It’s a real-time visualization of global wind patterns. It looks like a Van Gogh painting, with swirling neon lines showing how air moves across the oceans. It’s an earth map that doesn't care about borders or cities; it only cares about the physics of the atmosphere.

Practical Ways to Use This Information

If you want to actually use an earth map like a pro, stop just looking for your house. There are better ways to engage with the planet.

- Compare Projections: Go to a site called "The True Size Of." It lets you drag countries around a Mercator map to see how they actually compare. Dragging Canada over the equator is a massive eye-opener. It shrinks.

- Contribute to the World: If you live in an area where Google Maps is a bit "off," hop onto OpenStreetMap. You can add your favorite local park trail or a new coffee shop. You’re helping build a more accurate global record.

- Check the Altitude: Most people forget the "Terrain" or "Topo" layers. Understanding the elevation of where you live or where you’re traveling changes how you see the landscape. It explains why some roads curve the way they do and why certain areas flood.

- Look at the Past: Use Google Earth’s "Timelapse" feature. It’s the most powerful version of an earth map ever created. You can watch thirty years of urban sprawl in Las Vegas or the drying up of the Aral Sea in seconds.

Actionable Insights for the Curious

The next time you look at an earth map, remember it's a model, not the thing itself. To get the most out of modern cartography:

- Switch to Globe View: If you’re using a desktop, always zoom out until the map becomes a sphere. This eliminates the Mercator distortion and gives you a true sense of the distance between continents.

- Verify with Multiple Sources: Don't rely solely on one provider. Apple Maps, Google Maps, and Waze all use different data sets and algorithms for traffic and routing. For hiking, apps like AllTrails or Gaia GPS use US Geological Survey data that is far superior for off-road navigation.

- Understand Data Privacy: Maps track you. To provide "live traffic" updates, companies monitor the speed of millions of phones. If you’re concerned about privacy, look into offline map tools like Organic Maps, which use OSM data without tracking your every move.

The earth map is no longer a static image on a wall. It is a living, breathing digital twin of our world. It’s flawed, biased, and beautiful all at once. By understanding those flaws, you actually see the world more clearly.