You’ve probably seen it hanging on a dusty wall in a doctor’s office. A grid of numbers that basically tells you if you're "normal" or not. It’s the average height weight chart, a tool that has sparked more anxiety than almost any other piece of paper in medical history. Honestly, it’s a bit of a relic. But people still search for it every single day because we have this deep-seated need to know where we stand compared to everyone else. Are you "average"? Is that even a good thing?

Standardization is a funny thing. We want to be unique until it comes to our health, and then we desperately want to be right in the middle of the bell curve.

The Weird History of the Average Height Weight Chart

Most people assume these charts were designed by a room full of doctors and scientists obsessed with longevity. That’s actually not true. The roots of the average height weight chart actually go back to the insurance industry in the early 20th century. Companies like Metropolitan Life Insurance started looking at their policyholders to figure out who was most likely to die early. They weren’t trying to make you healthy; they were trying to calculate risk and set premiums.

📖 Related: Non Burping Fish Oil: Why Your Supplements Keep Repeating On You

By 1943, MetLife released their "Ideal Weights" table. It was based on "small," "medium," and "large" frames, though they never really defined what those frames actually meant. You were just supposed to guess if your elbows were wide or your wrists were thick.

It’s kind of wild when you think about it. For decades, our definition of a healthy weight was dictated by actuaries looking at data from a very specific, mostly white, middle-class population from the 1930s. We’ve been trying to fit modern, diverse bodies into a mold created for insurance profits nearly a century ago.

What the Numbers Actually Say Right Now

If we look at the most recent data from the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), which is part of the CDC, the "average" American has changed significantly. In the 1960s, the average man was about 5'8" and weighed 166 pounds. Today? The average adult male in the U.S. stands about 5'9" and weighs nearly 200 pounds. For women, the average height is roughly 5'3.5", with an average weight of about 170 pounds.

Does that mean being 200 pounds is the new healthy? Not necessarily.

There is a massive difference between "average" and "optimal." Just because the population is getting heavier doesn't mean our biological systems have evolved to handle the extra load without consequences. We’re seeing higher rates of Type 2 diabetes and hypertension, which suggests that the average height weight chart of today is a reflection of a public health crisis rather than a goal to strive for.

✨ Don't miss: Coffee For Health Benefits: Why Your Morning Cup Is Actually Doing More Than Just Waking You Up

Breaking Down the Math

When you look at a modern chart, it's usually sorted by Body Mass Index (BMI). This is the formula: your weight in kilograms divided by your height in meters squared.

$$BMI = \frac{weight(kg)}{height(m)^2}$$

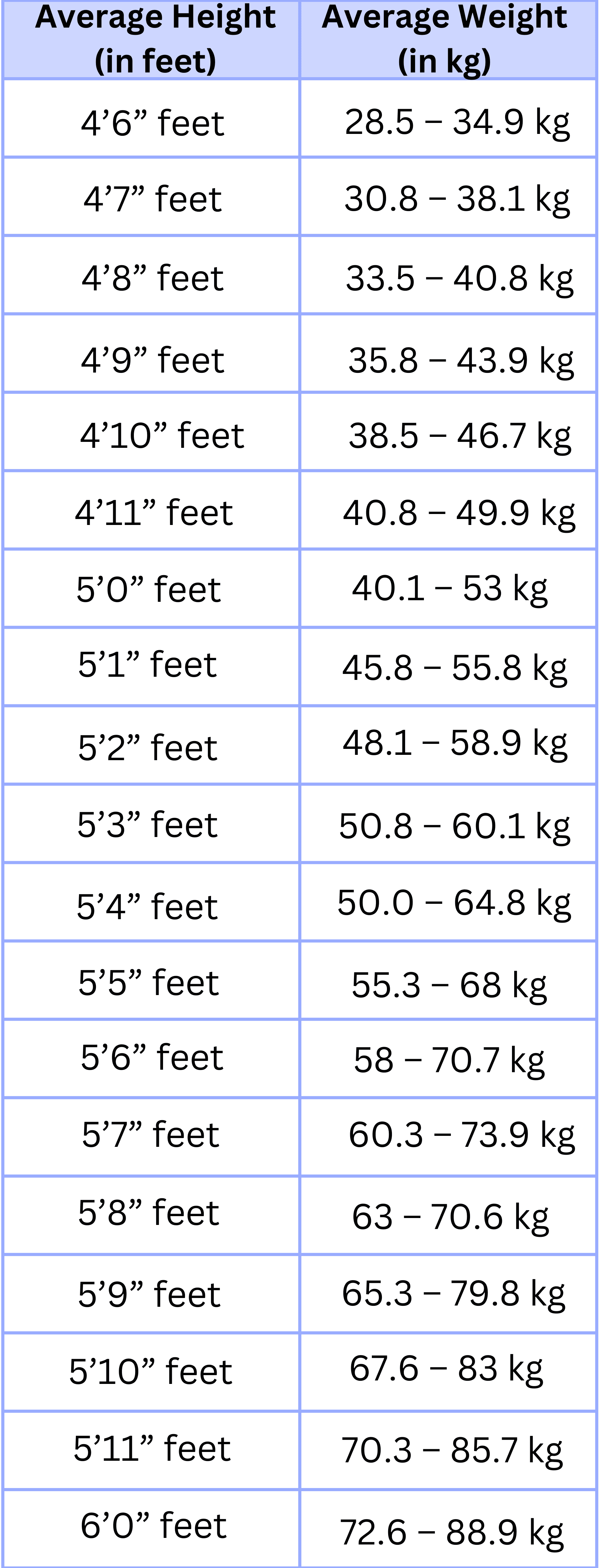

If you’re 5'10" (178 cm), the "normal" weight range on a standard average height weight chart is typically between 129 and 174 pounds. That’s a huge 45-pound window. If you're 5'4", the range is roughly 108 to 145 pounds.

But here is where it gets messy.

A 170-pound man who is 5'10" and runs marathons looks nothing like a 170-pound man of the same height who sits at a desk 12 hours a day and has never lifted a weight. The chart treats them exactly the same. It can’t see muscle. It can’t see bone density. It definitely can’t see where you carry your fat, which actually matters way more than how much you have in total.

Why the Chart Lies to Athletes and Older Adults

If you are someone who hits the gym four days a week, the average height weight chart is basically your enemy. Muscle is much denser than fat. You’ve probably heard that a million times, but it bears repeating because it breaks the BMI system.

Take a professional rugby player or a weightlifter. According to the chart, they are "obese." Their BMI might be 32 or 35. But their body fat percentage might be 12%. On the flip side, you have "skinny fat" individuals—people who fall perfectly within the "normal" range on a height weight chart but have high levels of visceral fat around their organs and very little muscle. These people often have the same metabolic risks as someone who is clinically obese, but the chart gives them a pass.

💡 You might also like: Is the One Chip Challenge Dangerous? The Truth Behind the Viral Trend

Then there’s the age factor.

As we get older, our bodies change. A study published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition suggested that for adults over the age of 65, being slightly "overweight" on the chart might actually be protective. It’s called the "obesity paradox." Having a little extra reserve can help seniors recover from falls or long illnesses. A strict adherence to the average height weight chart could actually lead to frailty in the elderly.

Better Ways to Measure Yourself

If the chart is flawed, what should you actually use? Most experts, including those at the Mayo Clinic, are moving toward a combination of metrics.

- Waist-to-Hip Ratio: This is a big one. It measures where you store fat. Carrying weight in your belly (apple shape) is linked to much higher risks of heart disease than carrying it in your hips (pear shape).

- Waist Circumference: Simply taking a tape measure to your natural waistline. For men, over 40 inches is a red flag. For women, it’s 35 inches.

- Body Fat Percentage: Tools like DEXA scans or even simple skinfold calipers give a much clearer picture of health than a scale ever will.

- Metabolic Markers: Honestly, your blood pressure, A1C levels, and cholesterol numbers tell a much deeper story than your relationship with gravity.

The Mental Toll of the Grid

We can't talk about these charts without talking about the psychological impact. For a lot of people, the average height weight chart is a source of shame. It’s a rigid box that doesn't account for ethnicity, genetics, or lifestyle.

Research has shown that weight stigma—the shame we feel when we don't fit the "average"—can actually cause people to avoid the doctor. They don't want to be lectured about a number on a scale that doesn't reflect how they actually feel. This avoidance leads to missed diagnoses and worse health outcomes. We have to stop looking at the chart as a moral scorecard. It’s just one data point. A single, blurry snapshot in a very long movie.

Practical Steps for Navigating Your Health

Don't throw your scale out the window just yet, but stop letting it dictate your self-worth. If you are looking at an average height weight chart and feeling discouraged, remember that health is a collection of habits, not a static number.

- Get a full panel. Instead of obsessing over being 10 pounds "over" the average, check your blood sugar and inflammation markers. Those are the numbers that actually predict your future health.

- Measure your waist. Use a soft tape measure once a month. If that number is trending down, you’re winning, even if the scale is stuck because you’re building muscle.

- Focus on performance. Can you walk up three flights of stairs without getting winded? Can you carry your groceries? Can you sleep through the night? These functional metrics are far more indicative of a healthy body than a chart made by an insurance company in the 40s.

- Acknowledge your frame. Some people are naturally "built." If you have broad shoulders and a wide ribcage, you will likely always be at the top end of the "average" range, or even slightly above it. That is perfectly fine as long as your cardiovascular health is solid.

The average height weight chart is a tool, but it's a blunt one. It’s like using a chainsaw to do surgery. It gives you a general idea of where the forest is, but it tells you absolutely nothing about the individual trees. Use it as a starting point for a conversation with a healthcare provider, but never let it be the final word on who you are or how healthy you can become. Health is found in the nuances, the daily movements, and the quality of the food you eat, none of which can be captured on a two-dimensional grid.