Ever looked at three different clocks in your house and realized they all disagree? It’s annoying. You’ve got the oven blinking 12:04, your phone saying 12:05, and that old wall clock lagging behind at 12:02. Most of us just shrug it off. But if you're trying to snag concert tickets the second they go on sale or sync up a complex server network, those seconds aren't just numbers. They're everything.

The secret to actually knowing what time it is—like, really knowing—is an atomic time clock online.

It sounds like something out of a 1950s sci-fi flick. In reality, it’s the backbone of the modern world. Without this precise timekeeping, GPS would fail, stock markets would crash, and your Uber would never find you. We think our phones are the gold standard because they update automatically, but they’re just the messengers. The real "source of truth" lives in labs using atoms to measure the pulse of the universe.

How an atomic time clock online actually works (and why it’s weird)

Standard clocks use a pendulum or a piece of quartz. Quartz is pretty good! When you run electricity through it, it vibrates at a specific frequency. But quartz is moody. It changes its tune based on temperature, pressure, or how old the battery is.

Atomic clocks don't care about the weather.

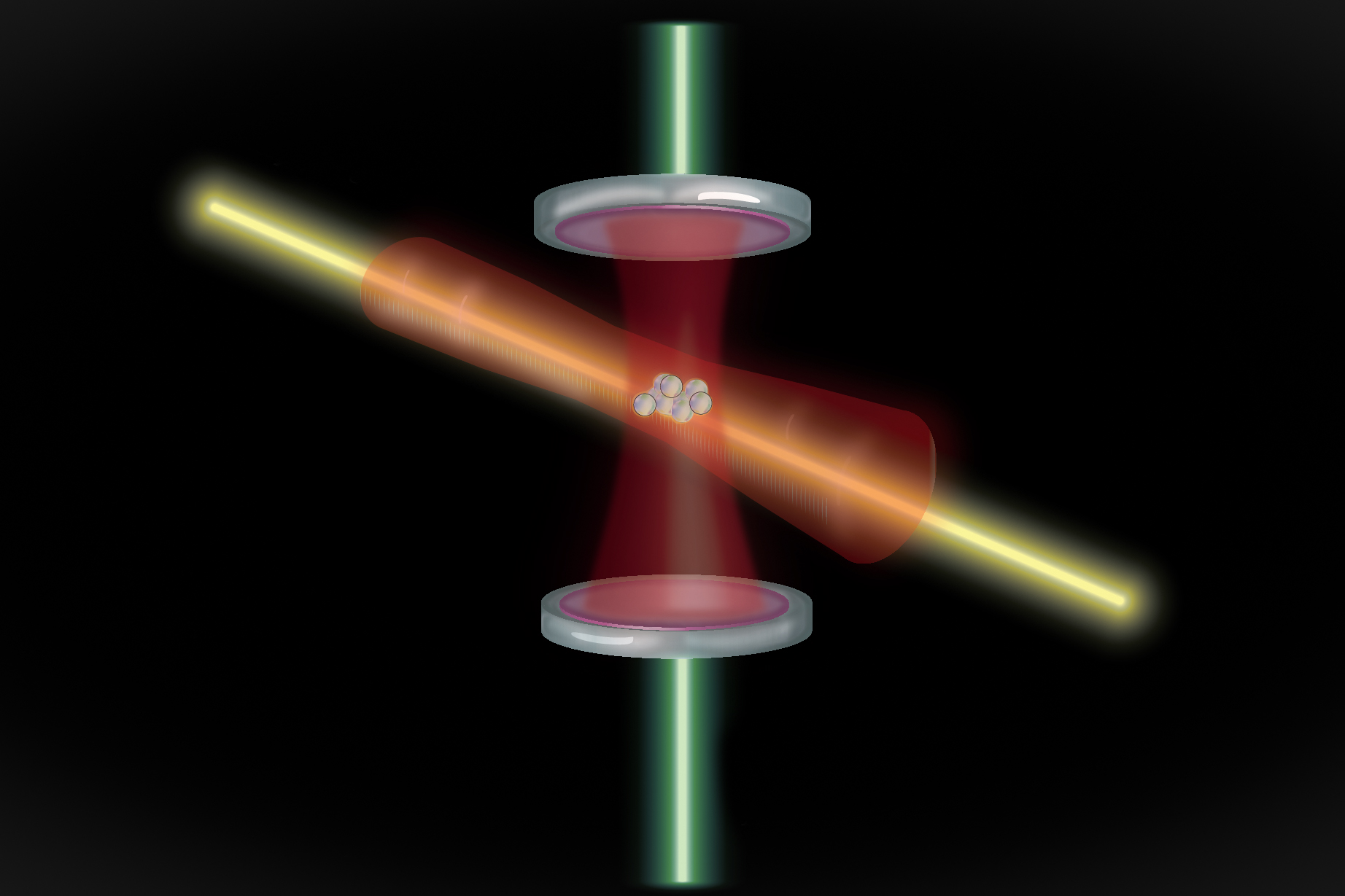

Instead of a vibrating rock, they use the vibrations of atoms—usually Cesium-133. Imagine an atom as a tiny, perfect metronome. According to the International System of Units (SI), a second is defined as exactly 9,192,631,770 oscillations of the radiation corresponding to the transition between two levels of the Cesium atom. That’s a lot of ticking.

When you check an atomic time clock online, you aren't looking at a clock in a warehouse. You are seeing a digital representation of a signal synced to a primary frequency standard. In the United States, that standard is maintained by NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology). Their NIST-F1 and NIST-F2 clocks in Boulder, Colorado, are so accurate they won't gain or lose a second in over 300 million years.

Honestly, it's overkill for boiling an egg. It's essential for the internet.

The lag factor

Here’s where people get tripped up. You go to a website to see the "official time," but is it actually right?

Not perfectly.

Because of "network latency," the time it takes for that data to travel from the NIST servers across the fiber optic cables and through your crappy home Wi-Fi to your screen introduces a delay. This is usually a few milliseconds. For most of us, 50 milliseconds doesn't matter. For high-frequency traders on Wall Street, 50 milliseconds is an eternity. They use specialized hardware and NTP (Network Time Protocol) to shave that delay down to almost nothing.

Why your computer clock is probably lying to you

Computers are surprisingly bad at keeping time on their own. Inside your laptop is a cheap quartz crystal. If you took your computer offline for a month, you’d likely find it’s drifted by several seconds or even minutes.

Operating systems like Windows, macOS, and Linux use NTP to periodically ping an atomic time clock online to correct themselves. But they don't do it constantly. Your computer might only check in once a day or every few hours. In between those "syncs," your clock is slowly drifting away from reality.

If you're wondering why your "online" clock looks different on two different websites, it's because they might be using different sync intervals or different server pools. Some use the Google Public NTP, others use the NTP Pool Project, and some point directly to NIST.

Does it matter for regular people?

Sometimes. Think about eBay snipers. If you're trying to place a bid in the final 0.5 seconds of an auction, you better hope your system clock is synced to a Tier-1 time server. Or consider two-factor authentication (2FA). Those six-digit codes on your phone are often "Time-based One-Time Passwords" (TOTP). If your phone’s internal clock drifts too far from the server’s clock, your codes will fail. You'll be locked out of your email just because your phone forgot what time it was.

The heavy hitters: NIST, USNO, and BIPM

Who actually decides what time it is? It’s a bit of a committee effort.

👉 See also: The 13 Touch Bar MacBook Pro: What Most People Get Wrong

- NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology): These are the folks in Colorado. They operate radio station WWV, which broadcasts time signals across the country.

- USNO (U.S. Naval Observatory): They keep time for the military and the GPS constellation. If you use a GPS device, you are technically using an atomic clock in space.

- BIPM (International Bureau of Weights and Measures): Based in France, they coordinate "Coordinated Universal Time" (UTC). They take data from about 400 atomic clocks worldwide to make sure everyone is on the same page.

It's a weirdly democratic process. No single clock is "The King." Instead, it's a weighted average. If one clock in Japan starts acting wonky, the other 399 clocks basically vote it out of the calculation. This ensures that UTC remains stable.

Common misconceptions about online time

People often confuse "Atomic Time" with "GPS Time" or "Solar Time."

Solar time is based on the Earth's rotation. The problem? Earth is a terrible clock. It wobbles. It slows down when there are big earthquakes or changes in the tides. Because Earth is slow, we have to occasionally add "Leap Seconds" to UTC to keep our atomic clocks aligned with the sunset.

Interestingly, tech giants like Meta and Google hate leap seconds. They cause massive bugs in distributed databases. Google actually "smears" the leap second, adding tiny fractions of time throughout the day so their servers don't freak out.

When you use an atomic time clock online, you are usually seeing UTC. This is the global standard. It doesn't change for Daylight Savings. It doesn't care about your time zone. Your local time is just an "offset" from that master UTC signal.

How to get the most accurate time on your device

If you want your desktop to be as precise as possible, don't just look at a website. Websites are for humans to glance at. For your machine to be accurate, you need to dig into the settings.

On Windows, you can force a sync by going to Date & Time settings and clicking "Sync now." But if you’re a pro, you’ll point your NTP settings to time.nist.gov or pool.ntp.org.

For the real nerds, there’s PTP (Precision Time Protocol). This is used in industrial settings and can keep clocks synced within nanoseconds. You probably don't need that to make sure you're not late for a Zoom call, but it's cool that it exists.

The future: Optical clocks

As if Cesium clocks weren't accurate enough, scientists are now working on optical clocks. These use atoms like Strontium or Ytterbium. Instead of microwaves, they use visible light, which vibrates much, much faster.

These clocks are so sensitive they can measure "time dilation." If you raise an optical clock by just a few centimeters, it will tick slightly faster because it’s further away from the Earth's gravity. It’s Einstein’s Theory of Relativity in action, right on a lab bench.

Eventually, the definition of the "second" will likely change to be based on one of these optical clocks. But for now, the Cesium-based atomic time clock online remains our best bet for keeping the world running.

Practical Steps for High-Precision Timing

If you actually need precision—maybe for amateur radio, high-stakes trading, or scientific logging—relying on a browser window isn't enough. Browsers add layers of processing that mess with the visual display.

- Use a dedicated NTP client: Software like Meinberg NTP for Windows is way better than the built-in Windows Time service. It runs in the background and continuously disciplines your system clock.

- Hardwire your connection: Wi-Fi jitter is the enemy of time. A physical Ethernet cable provides a much more stable "trip time" for those time packets.

- Check your offset: You can use command-line tools like

w32tm /query /statuson Windows to see exactly how many seconds your computer differs from the reference server. - Trust the source: Stick to official government or academic portals. While third-party "what time is it" sites are fine for checking the hour, they often have higher latency than a direct ping to a Stratum 1 server.

Accuracy is a rabbit hole. For most, knowing the time within a second is plenty. But knowing that there's a massive, vibrating atom in a lab somewhere keeping the entire digital world from collapsing into chaos? That’s just cool.