You’ve probably seen the footage. It usually starts with someone poking a pile of mulch with a stick, only for the ground to literally erupt. It doesn’t look like a normal earthworm moving. It looks like a panicked snake or a fish out of water. If you’ve stumbled across an asian jumping worms gif while scrolling through gardening forums or Reddit, you know exactly the frantic, thrashing motion I’m talking about. It’s unsettling. Honestly, it’s a little gross. But that viral clip isn’t just a "weird nature" moment; it’s a visual warning of a massive ecological shift happening right under our feet across North America.

These things are aggressive. They don't just crawl; they leap.

Most people grew up thinking earthworms were the "good guys" of the soil. We were taught they aerate the ground and help plants grow. That’s true for the European species we’re used to, but these newcomers—Amynthas agrestis, Amynthas tokioensis, and Metaphire hilgendorfi—play by a completely different set of rules. When you see an asian jumping worms gif, you aren't just seeing a bug with a bad attitude. You are seeing a high-speed nutrient vacuum that can strip the life out of a forest floor in a single season.

The unmistakable signature of the "Snake Worm"

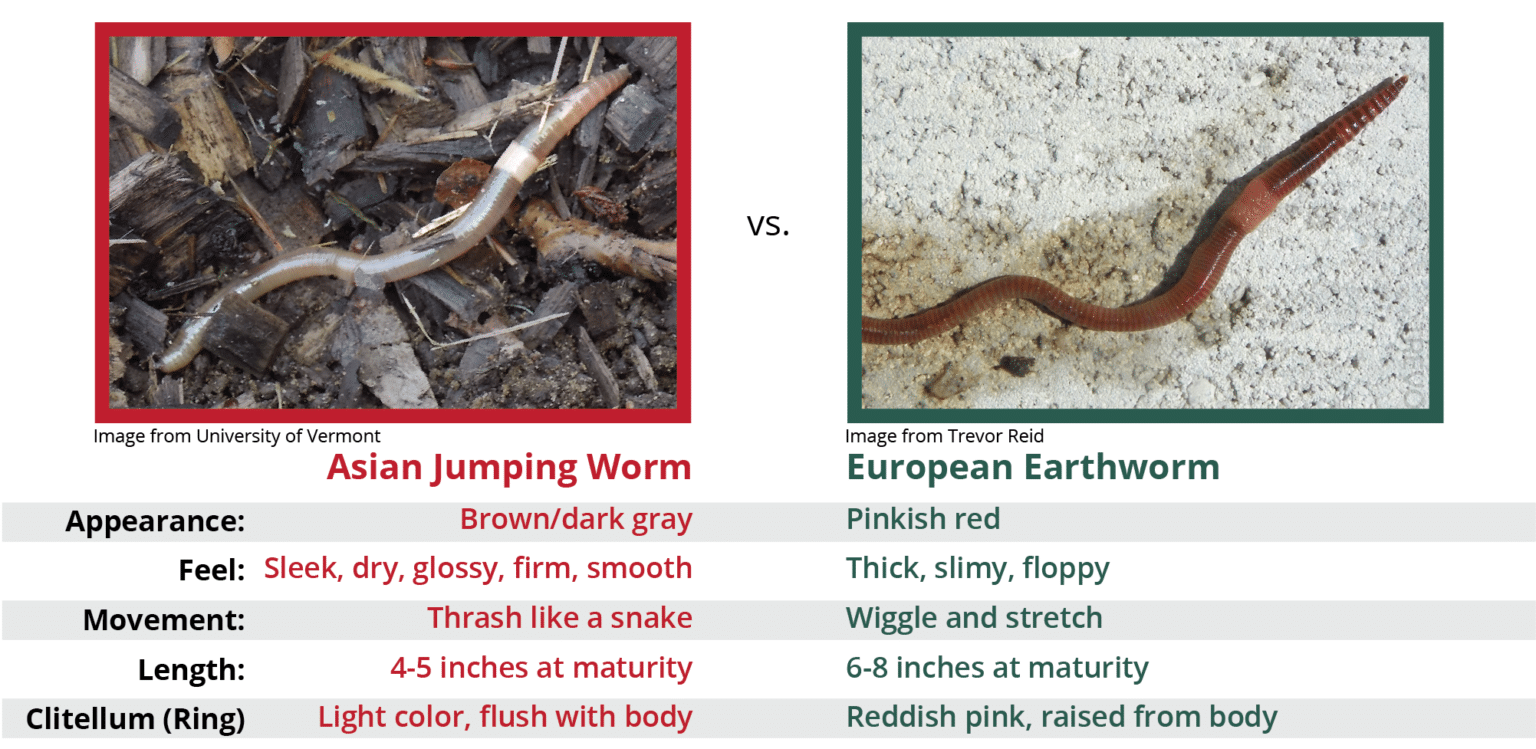

How do you know if what you’re looking at is actually a jumping worm? Look at the clitellum. That’s the band around the worm's body. On a standard nightcrawler, that band is thick, pinkish, and raised, sort of like a saddle. On a jumping worm, it’s milky white or light gray, completely flush with the body, and it circles the entire circumference like a ring. It’s also much closer to the head than on other species.

But really, the behavior is the dead giveaway.

If you touch a regular earthworm, it might wiggle or try to burrow deeper. If you touch an Amynthas worm, it will thrash violently from side to side. They’ve been known to actually jump off the ground or even shed their tails as a defense mechanism to escape predators. It’s this specific, high-energy movement that makes an asian jumping worms gif so shareable. It triggers a bit of that "uncanny valley" feeling because worms aren't supposed to move that fast. They are incredibly muscular for their size.

👉 See also: Sleeping With Your Neighbor: Why It Is More Complicated Than You Think

They also live in much higher densities than European worms. You won't find just one. You’ll find dozens, all tangled together just beneath the leaf litter. They don't go deep. While nightcrawlers might dive six feet down to survive the winter, jumping worms stay in the top few inches of soil. They live fast, eat everything, and die with the first frost, leaving behind millions of tiny, tea-seed-sized cocoons that are nearly impossible to spot.

Why your soil looks like coffee grounds

The most destructive part of their presence isn't their jumping; it's their poop. Biologists call it "castings."

Healthy soil has a specific structure. It’s held together by fungi and organic matter into a stable matrix that retains water. Jumping worms ruin this. They eat the organic "duff" layer—the decomposing leaves and twigs—at a rate that is frankly terrifying. They process it so quickly that the soil turns into loose, granular pellets that look exactly like dried coffee grounds.

Once the soil reaches this "coffee ground" state, it loses its ability to hold onto moisture or nutrients. Rain simply washes the topsoil away because there’s nothing holding it down anymore. Native plants, especially those in forests like trilliums or lady slippers, can’t germinate in this stuff. Their roots can’t find purchase. We are seeing entire forest understories vanish because the soil has been structurally compromised by these invaders. If you see a video or an asian jumping worms gif where the soil looks like it's boiling, that's the granular texture in action. It’s a sign of a dying ecosystem.

The "Great Worm Myth" and the history of invasion

It’s a bit of a shock to most people to learn that almost all earthworms in the northern United States are invasive. The glaciers that covered the region 10,000 years ago wiped out the native species. The "good" worms we have now came over with European settlers in the root balls of plants or as ship ballast.

✨ Don't miss: At Home French Manicure: Why Yours Looks Cheap and How to Fix It

The Asian species arrived much later, likely in the late 19th or early 20th century, but they didn't really start exploding across the Midwest and Northeast until the last few decades. Dr. Josef Görres at the University of Vermont has been one of the leading voices tracking this spread. He and other researchers have noted that these worms don't just displace other worms; they change the chemistry of the earth. They increase the rate of nitrogen cycling so much that the plants can't keep up, leading to nutrient leaching into local waterways.

It’s a biological wildfire.

And we are the ones spreading it. The primary way these worms move into new gardens is through mulch, compost, and shared perennials. A well-meaning neighbor gives you a hosta from their yard, and tucked into that soil are three or four cocoons. By mid-summer, your entire backyard is thrashing.

Can you actually get rid of them?

Here is the hard truth: there is no "magic spray" for jumping worms. Because they are so similar to beneficial worms, most chemical pesticides that would kill them would also wipe out the rest of your soil's microbiome.

However, we are seeing some success with a few "low-tech" methods.

🔗 Read more: Popeyes Louisiana Kitchen Menu: Why You’re Probably Ordering Wrong

- Solarization: This is probably the most effective way to clear an area before planting. You lay down clear plastic over your garden beds during the hottest part of the summer. The goal is to get the soil temperature above 104°F (40°C) for at least three days. This kills the cocoons.

- Saponins: Some gardeners use organic fertilizers derived from tea seed meal. These contain saponins, which are natural soaps that irritate the worms' skin and force them to the surface, where they can be collected and destroyed.

- The "Mustard Pour": If you want to see if you have them, mix a gallon of water with a 1/3 cup of ground yellow mustard seed. Pour it over a square foot of soil. It’s not a permanent fix, but the mustard irritates the worms and brings them to the surface for ID. Watching them react to this is basically like seeing an asian jumping worms gif in real-time.

- Manual Removal: It’s tedious, but it works for small plots. Catch them, put them in a plastic bag, and let them sit in the sun. Or drown them in vinegar or rubbing alcohol. Just don’t throw them back into the woods.

Biological hope on the horizon?

Researchers are looking into fungal pathogens that might specifically target Amynthas species. Beauveria bassiana is a fungus that already exists in many soils and has shown some promise in laboratory settings for controlling jumping worm populations. But we aren't at the stage of a commercial product yet. Nature usually finds a balance eventually, but "eventually" in ecological terms can mean decades or centuries. In the meantime, the burden falls on us to stop the spread.

What you should do right now

If you’ve seen that asian jumping worms gif and realized your garden has those same symptoms, don't panic, but do take it seriously.

First, stop trading plants with soil. If you're moving perennials, wash the roots completely clean of soil before giving them away or moving them to a new part of your property. This "bare-root" method is the only way to ensure you aren't transporting cocoons.

Second, be very careful about where you buy mulch. Buy from reputable suppliers who heat-treat their compost to high temperatures. If the compost hasn't reached the "thermophilic" stage (where it gets hot enough to steam), it’s a potential Trojan horse for jumping worm eggs.

Third, report your sightings. Most state universities and DNRs have tracking maps (like EDDMapS) to help scientists understand how fast these invaders are moving. Your "gross worm video" is actually valuable data.

Ultimately, we have to change how we think about the ground. Soil isn't just "dirt"; it's a living organ. When something like the Asian jumping worm moves in, it’s like a parasite affecting that organ. It's not the end of gardening, but it is the end of gardening as we used to know it. We have to be more intentional, more sterile in our transfers, and more observant of the small movements beneath the leaves.

Practical Checklist for Gardeners

- Inspect your mulch: Look for the "coffee ground" texture before you spread it.

- The 104-degree rule: If you suspect cocoons in your compost, solarize it under clear plastic in the sun.

- Bag and bake: If you find the worms, put them in a sealed bag and leave them in the sun to die.

- Clean your boots: If you hike in an infested forest, scrub your treads before walking into your own yard. Cocoons travel in the mud on your soles.

- Bare-root only: Never move soil from one site to another if you can avoid it.

The more we share the reality behind the asian jumping worms gif, the better chance we have of slowing them down. It’s about protecting the long-term health of the woods and the birds that rely on those forest floor insects. Keep your eyes on the dirt.