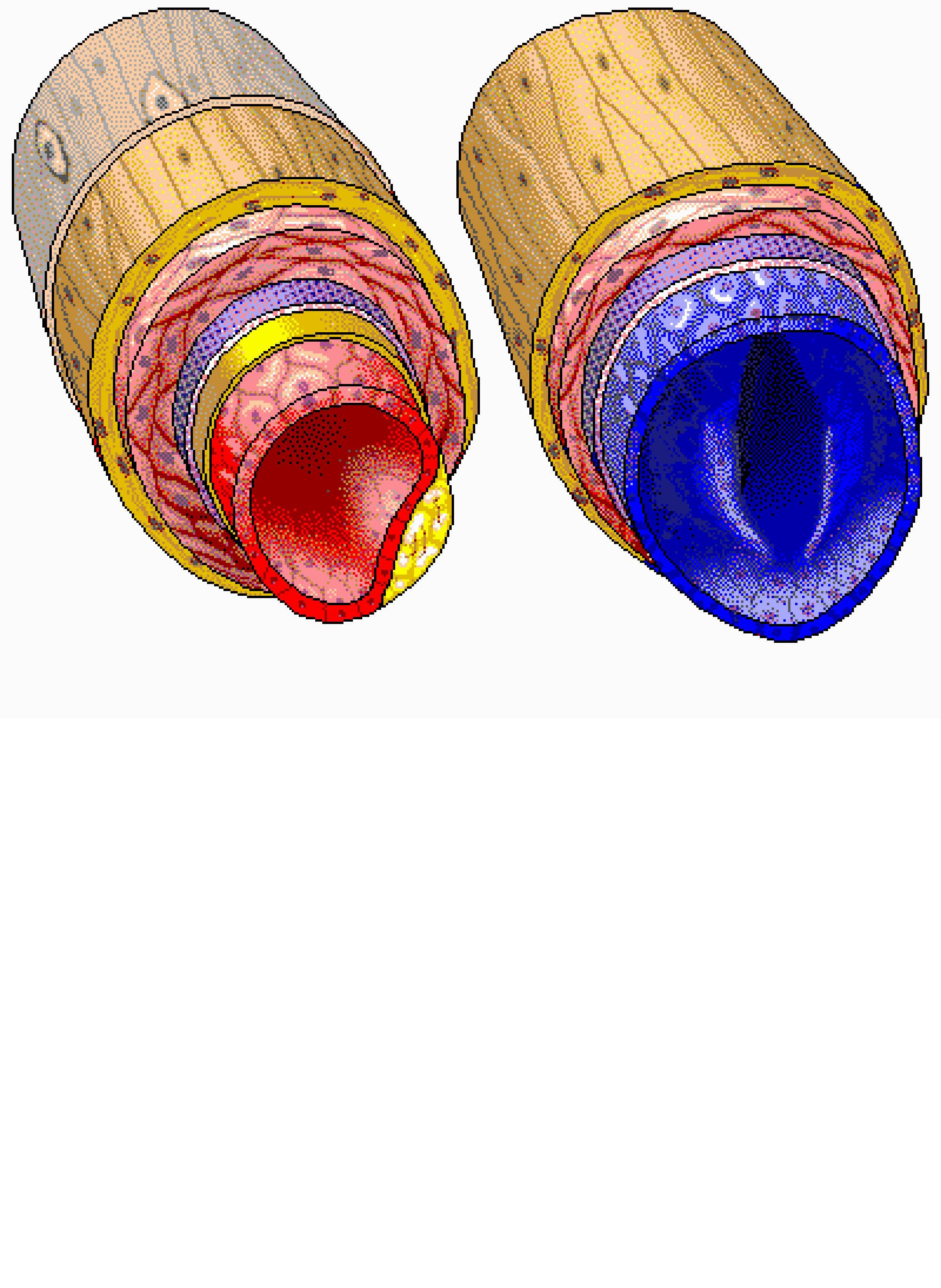

You've probably seen the diagrams in old biology textbooks. One is a bright red circle, the other is a floppy blue oval. It looks simple. But honestly, if you ever look at a real artery and vein cross section on a histology slide, it’s a mess of wavy lines, jagged edges, and weirdly thick walls. It’s not just about the color. It’s about how these things survive the constant, pounding pressure of your heartbeat without literally bursting open.

Think about your garden hose. Now think about a thin plastic grocery bag. That’s basically the structural difference we’re talking about here.

The Three Layers Everyone Forgets

If you slice through a blood vessel, you aren't just looking at a tube. You're looking at a sandwich. Both arteries and veins have three distinct layers, or "tunics."

The inner layer, the tunica intima, is basically a slick "slip-n-slide" for your blood cells. It’s lined with endothelial cells. If these get rough or damaged, you’re looking at clots. Then there’s the tunica media. This is the middle child, and in an artery, it’s the star of the show. It’s packed with smooth muscle and elastic fibers. Why? Because when your heart pumps, it’s like a hammer blow. The artery has to stretch out and then snap back. If it didn't have that thick muscle layer, it would just stay stretched out like a loose sock.

The outer layer is the tunica externa. It’s mostly collagen. It’s the anchor that keeps your blood vessels from sliding around inside your arm or leg like loose spaghetti.

Why the Artery Stays Round

When you look at an artery and vein cross section side-by-side, the artery almost always keeps its shape. It looks like a sturdy doughnut. This is because of the pressure. Arteries are high-pressure systems. Even when they’re empty, they have enough structural integrity—thanks to that beefy tunica media—to stay open.

Take the aorta. It’s the biggest artery you’ve got. Its cross section reveals an incredibly thick wall because it’s taking the full force of the left ventricle. If you compare that to a tiny arteriole, the proportions change, but the "roundness" usually stays.

📖 Related: Whooping Cough Symptoms: Why It’s Way More Than Just a Bad Cold

Veins? They’re the opposite.

In a cadaver or a lab slide, a vein usually looks like a collapsed, irregular slit. It’s floppy. Since veins are low-pressure return tracks, they don’t need those heavy-duty reinforced walls. They just need to get the blood back to the heart without too much friction. If you press on your skin, you're easily squishing your veins. You’d have to press much harder to collapse an artery.

The Secret Weapon: The Internal Elastic Membrane

Here is a detail most people miss. If you zoom in really close on an artery and vein cross section, you’ll see a squiggly, dark line in the artery that you won't see in the vein. That’s the internal elastic membrane.

It looks like a tiny piece of crumpled-up tinfoil.

This membrane allows the artery to expand. When the heart relaxes (diastole), this membrane recoils. This "elastic recoil" is actually what keeps your blood moving between heartbeats. Without it, your blood flow would be jerky—starting and stopping with every pulse. Veins don't have this. They don't need to bounce back because the blood inside them isn't pulsing; it's just sort of... flowing. Like a lazy river.

Valves: The Vein’s Only Advantage

Because veins are working against gravity—especially the ones in your legs—they have something arteries don't. Valves.

👉 See also: Why Do Women Fake Orgasms? The Uncomfortable Truth Most People Ignore

In a cross section, you might see these little flaps of tissue sticking out into the lumen (the open space in the middle). These are one-way doors. They let blood go up toward the heart but slam shut if the blood tries to leak back down. When these valves fail, you get varicose veins. The vein stretches out because blood is pooling, and eventually, the vessel looks twisted and gnarly under the skin.

Arteries don't have valves. They don't need them. The heart provides all the "push" they need.

Real World Consequences of Vessel Structure

Understanding this isn't just for passing a med school quiz. It explains why certain diseases happen where they do.

- Aneurysms: These mostly happen in arteries. Why? Because if that thick muscular wall weakens, the high pressure creates a "balloon" effect.

- Phlebitis: This is inflammation of the vein. Since vein walls are thin, they are much more susceptible to external injury or irritation from IV needles.

- Arteriosclerosis: This is the "hardening" of the arteries. The elastic fibers in the tunica media get replaced by stiff minerals. The artery loses its ability to "snap back," which makes the heart work way harder.

Distinguishing Them Under the Microscope

If you're ever looking at a slide and can't tell which is which, look at the lumen size relative to the wall thickness.

- Artery: Small, neat, circular lumen. Very thick, muscular wall.

- Vein: Large, floppy, irregular lumen. Very thin wall.

Usually, in the body, an artery and a vein run right next to each other, often accompanied by a nerve. This is called a neurovascular bundle. In these bundles, the vein will almost always look twice as large as the artery, but its walls will be a fraction of the thickness.

Actionable Insights for Vascular Health

You can't change the anatomy you were born with, but you can definitely influence how these cross sections look over time.

✨ Don't miss: That Weird Feeling in Knee No Pain: What Your Body Is Actually Trying to Tell You

Watch your "Pulse Pressure." This is the difference between your top and bottom blood pressure numbers. A wide gap often means your arteries are losing their elasticity (that internal elastic membrane we talked about). If your pulse pressure is consistently over 60, it's time to talk to a doctor about arterial stiffness.

Move your calves. Since veins have thin walls and rely on surrounding muscles to "squeeze" blood upward, sitting still is their worst enemy. The "muscle pump" in your legs is basically a secondary heart for your venous system.

Hydration matters for the Intima. That inner "slip-n-slide" layer works best when your blood isn't sludge. Dehydration makes blood more viscous, which puts more friction on the endothelial lining of both your arteries and veins.

Check your Vitamin C and Copper. These are the building blocks of collagen and elastin. Without them, the tunica externa and tunica media can't repair themselves properly.

By paying attention to the structural reality of these vessels, you're not just looking at a diagram. You're looking at the plumbing that keeps you alive. Keep the pressure low to protect the arteries, and keep moving to support the veins.