If you’ve ever stared at an Ardennes Battle of the Bulge map and felt like your brain was short-circuiting, don’t worry. You're not alone. It looks like a toddler took a blue and red crayon to a map of Belgium and just went nuts. But that mess of lines represents the largest and bloodiest battle fought by the United States in World War II. It was a cold, miserable, and incredibly confusing six-week slog that changed the course of history.

December 16, 1944. That’s the date it all kicked off. Hitler was desperate. He thought he could split the Allied lines, capture the port of Antwerp, and force a peace treaty. He was wrong, obviously, but for a few weeks there, things looked pretty grim. The "bulge" in the map wasn't just a military term; it was a literal protrusion of German forces into Allied-held territory, creating a precarious situation that nearly derailed the Western Front.

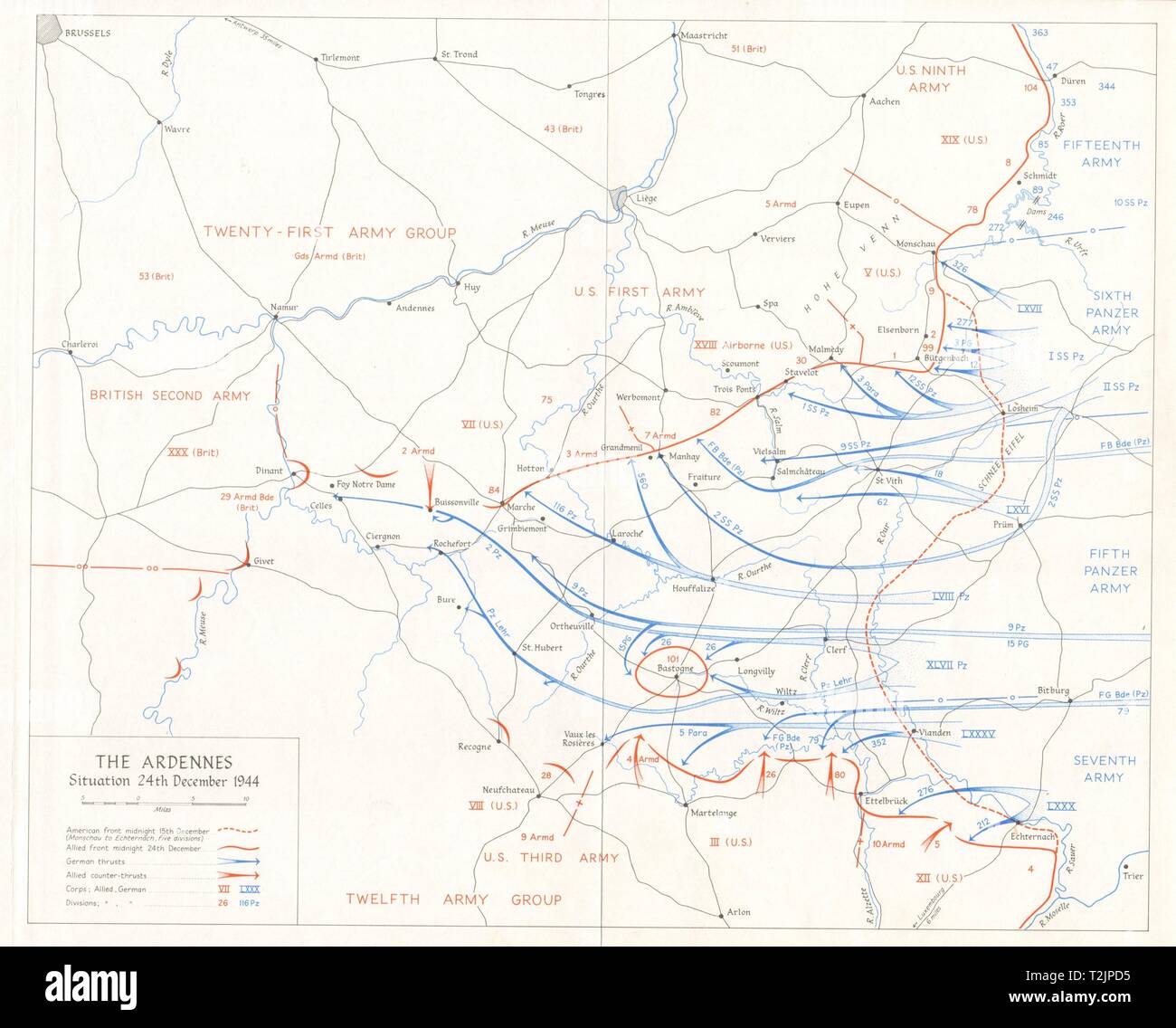

The Geography of a Nightmare

The Ardennes isn't exactly where you'd choose to fight a tank battle. It’s dense. It’s hilly. It’s full of narrow, winding roads that turn into mud pits the second a Tiger tank rolls over them. When you look at an Ardennes Battle of the Bulge map, you see these tiny villages like Bastogne, Houffalize, and St. Vith. These weren't major metropolises. They were crossroads.

In the Ardennes, if you controlled the crossroads, you controlled the war.

The Germans needed those roads to move their heavy panzers toward the Meuse River. The Allies, caught off guard and spread thin, had to hold those junctions at all costs. This led to the "island" defense strategy. Instead of a solid front line, you had these pockets of American GIs hunkered down in frozen foxholes, surrounded on all sides, refusing to budge. It’s why the map looks so fragmented. It wasn't two lines clashing; it was a series of brutal, isolated brawls in the snow.

Most people think the Ardennes was just one big forest. Honestly, it’s more of a plateau cut by deep river valleys. The Our River, the Ambleve, the Salm—these aren't just names on a page; they were lethal obstacles. Engineers on both sides spent half the battle blowing up bridges or trying to build new ones under fire. If you’re looking at a detailed topographic map, you’ll notice the elevation changes are brutal. Moving an army through there in a blizzard is basically a logistical suicide mission.

Why the "Bulge" Actually Bulged

So, why the shape? Why that weird, rounded protrusion that gives the battle its name?

💡 You might also like: Human DNA Found in Hot Dogs: What Really Happened and Why You Shouldn’t Panic

The German Sixth Panzer Army attacked in the north, the Fifth Panzer Army in the center, and the Seventh Army in the south. The center moved the fastest. General Hasso von Manteuffel—a name you’ll see in every serious history book—pushed his troops hard. They bypassed American strongpoints, flowing around them like water around a rock. This created the deep penetration that shows up as the "bulge" on the Ardennes Battle of the Bulge map.

The northern shoulder, near Elsenborn Ridge, held firm. That’s a crucial detail people often miss. If the Germans had broken through there, they would have had a straight shot to their objectives. But the 2nd and 99th Infantry Divisions fought like hell. Because the north and south "shoulders" stayed put while the center collapsed, the line stretched into that iconic, terrifying shape.

It was a nightmare for everyone involved.

Imagine being a private in the 106th Infantry Division. You’ve been in Europe for a week. Suddenly, the entire German army is in your backyard. You're low on ammo, you're freezing, and your map tells you the nearest friendly unit is five miles away through a forest full of guys who want to kill you. That was the reality. The "map" for a soldier on the ground was often just the fifty yards of woods they could see through the fog.

The Bastogne "Hole" in the Map

You can't talk about an Ardennes Battle of the Bulge map without pointing at that little circle in the middle: Bastogne. It was a vital hub where seven main roads met. If the Germans wanted to keep their momentum, they needed Bastogne.

The 101st Airborne got there first.

📖 Related: The Gospel of Matthew: What Most People Get Wrong About the First Book of the New Testament

They were surrounded. Completely. On the map, Bastogne looks like a little blue dot in a sea of red. General McAuliffe’s famous "Nuts!" response to the German surrender demand isn't just a cool quote; it’s a reflection of the sheer stubbornness required to hold that spot. Patton’s Third Army eventually punched a hole through the southern flank to relieve them, which shows up on maps as a thin blue line slicing through the red mass. It’s one of the most dramatic moments in military cartography.

The relief of Bastogne on December 26th changed the geometry of the battle. The "bulge" stopped growing and started shrinking. But "shrinking" meant more weeks of grinding, bloody combat in knee-deep snow. The Germans didn't just pack up and leave. They fought for every yard of frozen dirt as they were pushed back toward the Westwall.

Logistics: The Unseen Lines on the Map

Maps usually show troop movements, but they rarely show the fuel lines. This battle was won and lost on gasoline. The German plan relied on capturing Allied fuel depots. They didn't.

At places like Stavelot, the Americans burned their own fuel supplies rather than let the Germans have them. When you see those red arrows on an Ardennes Battle of the Bulge map suddenly stalling out or veering off course, it’s often because a tank commander realized he was running on fumes. Joachim Peiper’s Kampfgruppe, the tip of the German spear in the north, ran out of gas and had to abandon dozens of perfectly good tanks and walk back to Germany.

Think about that. One of the most feared units in the SS, defeated by an empty gas tank.

The weather also played a massive role that no static map can truly capture. For the first week, a thick "Hitler Weather" fog kept Allied planes grounded. The map was a two-dimensional fight. Once the skies cleared around December 23rd, the map became three-dimensional. P-47 Thunderbolts started screaming down from the clouds, turning those congested German road columns into scrap metal. The movement of the front lines accelerated almost immediately once the sun came out.

👉 See also: God Willing and the Creek Don't Rise: The True Story Behind the Phrase Most People Get Wrong

How to Read a Battle Map Without Going Insane

If you're looking at a map of this battle for a school project or just because you’re a history nerd, here’s how to actually digest it.

- Look at the roads, not just the units. The road network dictates everything. If a unit isn't on a road, they're probably stuck in a ravine.

- Check the dates. A map from December 18th looks radically different from one on Christmas Day. The situation was fluid.

- Identify the "Shoulders." Look at the top (Monschau/Elsenborn) and the bottom (Echternach). As long as those held, the Germans were essentially funneled into a trap.

- Notice the rivers. Any line that follows a jagged path is likely a river. These were the natural defensive lines where the Americans finally stopped the bleeding.

The scale is also deceptive. The Ardennes is a big place, but the actual fighting happened in cramped spaces. A "regimental front" that should have covered a mile might have been stretched over five miles. There were massive gaps in the lines. That’s why German saboteurs, like those in Operation Greif, were able to slip through wearing American uniforms and flip road signs around. They used the map as a weapon.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Map

A common mistake is thinking the "Bulge" was a planned shape. It wasn't. It was an accident of resistance. The Germans wanted a breakthrough, not a bulge. A bulge means you’re surrounded on three sides. It’s a terrible place to be. By early January 1945, the German position was a disaster waiting to happen.

Another misconception? That the battle ended when Bastogne was relieved.

In reality, some of the heaviest fighting happened in January as the Allies "squeezed" the bulge from both sides. The map shows the line slowly flattening back out, but it doesn't show the thousands of men who died in those final weeks. It was a war of attrition at that point. The Germans were throwing 16-year-olds and old men into the line. The Americans were exhausted.

Actionable Steps for Exploring the Ardennes Legacy

If you really want to understand the Ardennes Battle of the Bulge map, you have to go beyond just looking at a screen. You need to see how the terrain dictated the tactics.

- Use Google Earth Pro: Don't just look at a 2D map. Turn on the 3D terrain feature for the area around Houffalize and Bastogne. You’ll immediately see why the Germans couldn't just "drive around" the American defenses. The ravines are steep and the forests are impenetrable.

- Visit the Bastogne War Museum: If you're ever in Belgium, this is the gold standard. They have interactive maps that overlay troop movements onto the modern landscape. It makes the "lines on paper" feel very real.

- Study the 1:50,000 Scale: If you can find reprints of the original tactical maps used by officers in 1944, grab them. The level of detail—down to individual farmhouses—shows you how intimate the combat was.

- Trace a Specific Unit: Instead of trying to understand the whole 80-mile front, pick one unit, like the 28th Infantry Division (the "Bloody Bucket"). Follow their specific retreat and stand. It turns the chaotic map into a coherent story of survival.

- Look for the "Ghost" Lines: Many maps today show the Siegfried Line (Westwall) bunkers. Seeing where the German offensive started from helps you realize how much ground they actually gained—and how much they eventually lost.

The Battle of the Bulge wasn't won by a brilliant general moving pins on a board in a warm room. It was won by guys in wet boots who refused to give up a nameless hill or a muddy intersection. When you look at an Ardennes Battle of the Bulge map, see past the arrows and the symbols. See the ridges, the rivers, and the roads that forced thousands of men into a meat grinder in the coldest winter in decades. That’s the only way the map starts to make sense.

The "Bulge" eventually vanished, but the scars on the landscape—and the maps we use to remember them—are still there. Understanding the geography is the first step to understanding why the soldiers who fought there called it "green hell," even when it was covered in white snow.