You’ve probably seen the meme. It’s a picture of a giant, rolled-up piece of paper with a caption saying it’s a 1:1 scale map of the world. It’s funny because it’s absurd. But if you actually stop and think about the logistics of an actual size world map, you run into some of the most fascinating headaches in mathematics, geography, and philosophy.

Honestly, the idea of a 1:1 map is a bit of a legendary trope in literature. Jorge Luis Borges wrote a famous one-paragraph story called On Exactitude in Science. In it, he describes an Empire where the Art of Cartography attained such "Perfection" that they built a map of the Empire that was the same size as the Empire itself. It coincided point for point. But subsequent generations—who weren't quite so obsessed with maps—realized the thing was useless. They left it to rot in the deserts.

There's a reason we don't do this.

👉 See also: The Nostalgic Allure of Wallpaper Mac OS X: Why We Keep Going Back

The Math Problem That Ruins Everything

The first hurdle isn't even the size; it's the shape. Earth is an oblate spheroid. It’s a squashed ball. If you want an actual size world map, you have to decide if you’re building a globe or a flat sheet. If it’s a globe, you’ve just built a second Earth. If it’s a flat map, you are in for a world of pain known as Gaussian curvature.

Carl Friedrich Gauss, a total genius from the 19th century, proved his Theorema Egregium. It basically says you can't flatten a sphere onto a plane without stretching or tearing it. You've tried to flatten an orange peel, right? It splits. So, a flat, actual size map would be a distorted, torn mess that doesn't actually represent the real world accurately anyway.

Even if you managed to print a 1:1 scale map on some magical, indestructible material, where would you put it? If you laid it over the Earth, you’d be covering the very things you’re trying to look at. You’d have a map of a forest sitting right on top of the forest. It's redundant.

The Gall-Peters and Mercator Mess

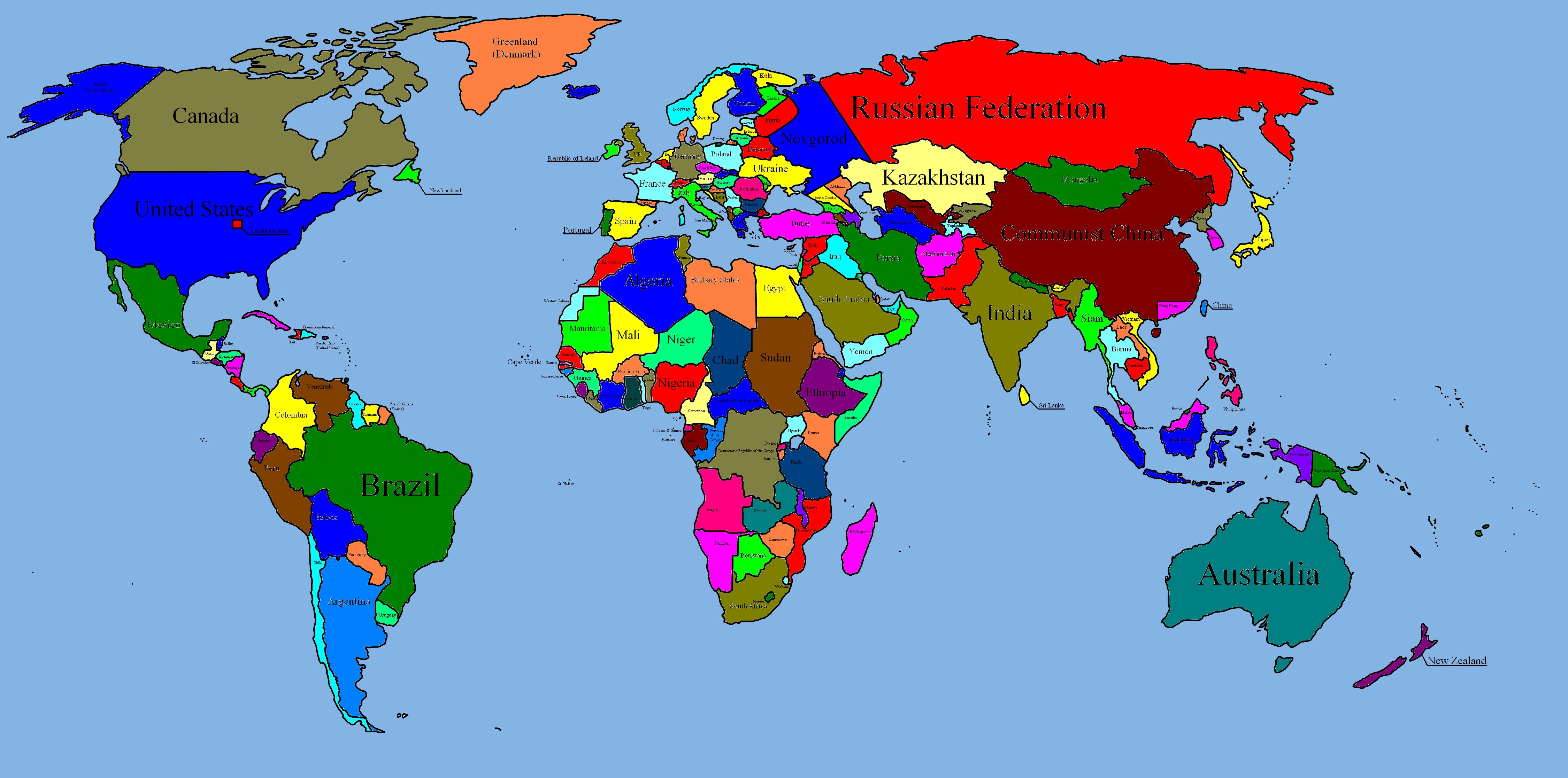

Most of us grew up with the Mercator projection. It’s the one where Greenland looks as big as Africa. It’s not. Africa is actually fourteen times larger than Greenland. This is the "Area vs. Shape" trade-off. Mercator kept the shapes right for sailors, but it blew up the sizes near the poles.

When people search for an actual size world map, they are often actually looking for a "True Size" map. They want to see how big countries really are compared to each other without the 16th-century navigational bias. Websites like The True Size Of allow you to drag China over the United States or move the UK over Madagascar. It’s eye-opening. You realize that Africa is absolutely massive—it can fit the US, China, India, and most of Europe inside its borders.

Why Scale Changes Everything

In cartography, "Large Scale" means a lot of detail (like a city map), and "Small Scale" means less detail (like a world map). It’s counterintuitive.

- 1:10,000 scale: One inch on the map is 10,000 inches in reality.

- 1:1 scale: One inch is one inch.

A 1:1 scale map of just a single human cell would be microscopic. A 1:1 scale map of the Grand Canyon would require millions of tons of paper. The logistics are a nightmare. Lewis Carroll—the Alice in Wonderland guy—also joked about this in his book Sylvie and Bruno Concluded. He mentioned a map with a scale of "a mile to the mile." The characters couldn't use it because the farmers complained it would cover the whole country and shut out the sunlight. So, they just used the country itself as its own map.

Digital Maps and the Illusion of Infinite Zoom

We kinda have an actual size world map now. It’s called Google Earth.

When you zoom in to the point where your house is on the screen, and you can see the individual tiles on your roof, you are looking at a high-resolution representation. But even then, it's not "actual size" on your monitor. It’s a projection of data. The data exists at a resolution of centimeters per pixel in some places, which is incredibly close to reality, but it’s still just a model.

The storage required for a truly 1:1 digital map with millimeter precision would be astronomical. We are talking about exabytes of data. And even then, the world changes. A 1:1 map becomes outdated the second a tree falls or a new sidewalk is poured.

The Coastline Paradox

Here is where things get really weird. If you want a truly accurate actual size world map, how do you measure the coastlines?

Benoit Mandelbrot, the father of fractal geometry, pointed out that the length of a coastline depends on the length of your ruler. If you use a kilometer-long ruler, you miss the bays. If you use a centimeter-long ruler, you measure around every rock and pebble. The smaller the ruler, the longer the coastline gets. Theoretically, if you measure at an atomic level, the coastline of Great Britain is infinitely long.

So, an actual size map is not just a physical impossibility; it’s a mathematical moving target. You can’t map what you can’t definitively measure.

👉 See also: How Long Were the Astronauts Stranded: The Starliner Saga and the 8-Month Wait Explained

Real-World Applications of Near-Actual Scale

We don't build 1:1 world maps, but we do build 1:1 maps of parts of things.

- Silicon Wafers: In chip manufacturing, the "map" used for lithography is essentially a 1:1 guide for where the transistors go.

- Medical Imaging: A high-res MRI can be thought of as a 1:1 map of a person's internal organs.

- Archaeology: Using LiDAR, researchers create 1:1 digital twins of ancient ruins hidden under jungle canopies.

These are useful because they are specific. A world map at that scale serves no purpose other than as a philosophical exercise or a very expensive piece of performance art.

What You Should Do Instead

If you’re fascinated by the scale of the world, don't look for a 1:1 map. You won't find one, and you wouldn't have anywhere to unroll it anyway.

Instead, look into Equal-Area Projections. The Mollweide projection or the Eckert IV projection are great if you want to see the "actual" size relationships of continents without the Mercator distortion. They look a bit "squashed" or "lobed," but they are much more honest about how much space countries actually take up on this planet.

Another great rabbit hole is the Dymaxion Map created by Buckminster Fuller. It projects the world onto an icosahedron (a 20-sided shape). When you unfold it, the landmasses are almost entirely undistorted in size and shape. It’s probably the closest thing we have to a "fair" map of the world.

The takeaway? All maps lie. They have to. To represent a 3D world on a 2D surface, you have to choose what to sacrifice: distance, direction, shape, or area. The only way to have an actual size world map that doesn't lie is to just walk outside and look at the ground. That’s the map. You’re standing on it.

Actionable Steps for Map Lovers:

- Check out the Gall-Peters projection to reset your brain’s understanding of the Global South’s size.

- Use Google Earth’s "Measure" tool to see the real distance between two points, which bypasses 2D map distortion.

- Read Borges' "On Exactitude in Science"—it takes 30 seconds and will make you feel like a philosophy professor.

- Buy a globe. Seriously. It’s the only way to see the world without the math of flat maps ruining the proportions.

Maps are just tools. Once you realize that every map is a compromise, you start seeing the world a lot more clearly.

---