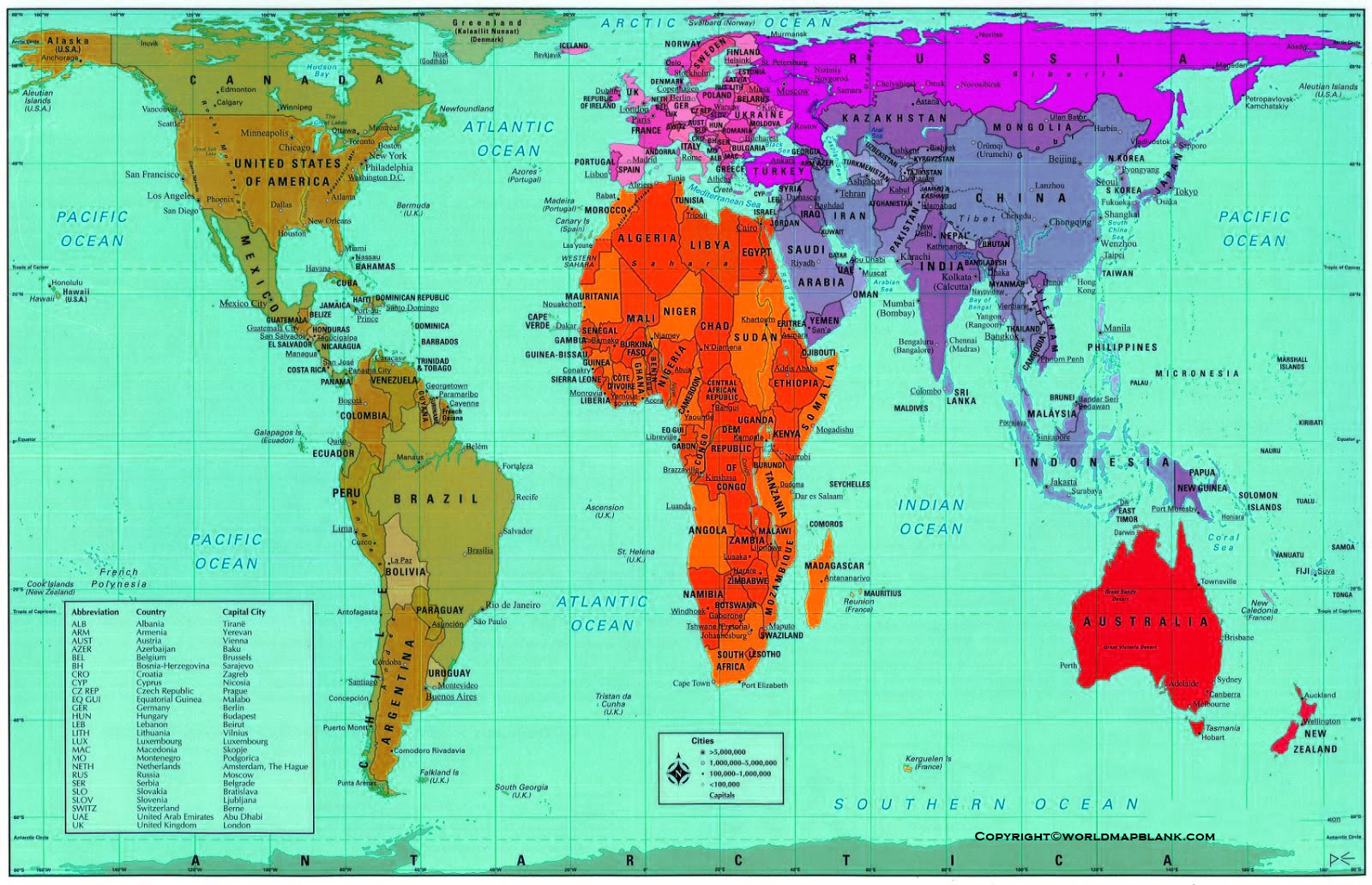

You’ve probably been lied to by a piece of paper your entire life. Look at the map on your wall, or the one you remember from third grade. See Greenland? It looks roughly the size of Africa. It’s huge. It’s imposing. It’s also a total lie. In reality, Africa is fourteen times larger than Greenland. You could fit the entire United States, China, India, and most of Europe inside Africa, and you’d still have room for a few smaller countries. This isn't just a minor "oops" from a cartographer; it's a fundamental mathematical problem that has shaped how we see the world for over 450 years.

Finding an accurate proportional world map is essentially the Holy Grail of geography. It’s hard. Like, "trying to flatten an orange peel without tearing it" hard. If you’ve ever tried to peel a Clementine and lay the skin flat on a table, you know the issue. It rips. It stretches. It bunches up. To make a map, you have to choose which way you’re going to cheat. You can keep the shapes right, or you can keep the sizes right, but you absolutely cannot do both on a flat surface.

The Mercator Problem

Gerardus Mercator was a smart guy. Back in 1569, he created a map that changed everything for sailors. His projection was a revolution because it allowed navigators to plot a course using straight lines. If you wanted to go from Lisbon to the West Indies, you drew a line, followed your compass, and you actually got there. That's a big deal when the alternative is dying at sea. But there’s a massive catch. To make those straight lines work, Mercator had to stretch the map more and more as you move away from the equator.

This is why everything near the poles looks bloated. It’s why Canada looks like a sprawling giant and Antarctica looks like an infinite white wasteland at the bottom of the page. Honestly, it’s kinda weird that we still use this for anything other than navigation. Yet, it’s the default for Google Maps and most school textbooks. We’ve been conditioned to see the Global North as massive and the Global South as tiny. It’s a distortion of reality that impacts how we perceive the importance of nations.

Why area matters more than you think

When we talk about an accurate proportional world map, we’re usually talking about "equal-area" projections. These are maps where one square inch in Brazil represents the exact same amount of land as one square inch in Siberia. Why does this matter? Well, think about climate change or population density. If you’re looking at a Mercator map to visualize where the world’s rainforests are, you’re getting a skewed perspective. The Congo Basin and the Amazon look much smaller than they actually are compared to the boreal forests of the North.

It’s about fairness, really.

📖 Related: Unlock iPhone Without Code: What Really Works (And What Is Just Clickbait)

Historians and geographers like Arno Peters argued in the 1970s that the Mercator map was inherently Eurocentric. By making Europe look larger and more central, it subtly reinforced colonial mindsets. While Peters wasn't the first to create an equal-area map—James Gall had done something similar in 1855—the "Gall-Peters" projection became a flashpoint for debate. It looks "stretched" and "ugly" to many because we’re so used to the Mercator distortion. Africa looks like a long, dripping teardrop. But guess what? That teardrop is much closer to the truth regarding its actual size.

The Contenders for the Crown

There isn't just one "correct" map. There are several, and each one has a specific job. If you’re looking for a truly accurate proportional world map, you have to decide what you’re willing to sacrifice.

The AuthaGraph: The New King?

In 2016, a Japanese architect named Hajime Narukawa won the Good Design Grand Award for something called the AuthaGraph. It’s wild. Narukawa figured out a way to divide the spherical surface of the Earth into 96 triangles, which he then projected onto a tetrahedron before flattening it into a rectangle.

It’s arguably the most accurate map we have.

It maintains the proportions of landmasses and oceans with incredible precision. But it looks... different. The continents are tilted at odd angles. The "up and down" we’re used to is gone. It’s a reminder that "North" is just a convention we agreed upon, not a physical law of the universe. The AuthaGraph is brilliant for seeing the world as a continuous surface, but it’s a nightmare if you’re trying to find your way home with a compass.

The Mollweide and the Eckert IV

If you want something that looks a bit more "map-like," you go for the Mollweide or the Eckert IV. These use an elliptical shape. They’re great for showing global distributions, like where the most CO2 is being emitted or how wealth is spread across the planet. They don't pretend the Earth is a rectangle. By curving the edges, they manage to keep the sizes accurate without making the continents look like they’ve been put in a taffy puller.

- Mollweide: Great for trade maps and global data.

- Eckert IV: Used frequently in National Geographic atlases because it balances shape and size well.

- Winkel Tripel: This is the one National Geographic adopted in 1998. It’s not a perfect equal-area map, but it "triples" the compromise between area, direction, and distance. It’s the "Goldilocks" of maps.

The Math of Flattening a Sphere

Let's get technical for a second. The Earth is an oblate spheroid. It’s fat at the middle because it’s spinning. When you try to project that onto a 2D plane, you’re dealing with Gaussian curvature. Carl Friedrich Gauss, a total genius, proved in his Theorema Egregium that you can’t flatten a sphere without distortion. It’s mathematically impossible.

$$K = \frac{1}{R^2}$$

In this formula, $K$ represents the Gaussian curvature. For a sphere with radius $R$, the curvature is constant and positive. A flat sheet of paper has a curvature of zero. Because these numbers aren't the same, you're always going to have to "tear" or "stretch" the geometry to make it fit. This is why every accurate proportional world map you see is actually just a very clever compromise.

People get really heated about this. There was a whole episode of The West Wing dedicated to the Gall-Peters projection. Cartographers (the people who make maps) often find the public's obsession with "the one true map" a bit exhausting because they know it’s all about the right tool for the right job. You wouldn't use a hammer to screw in a bolt, right? So you wouldn't use an equal-area map to navigate a ship.

How to actually use this information

Stop trusting the first map you see. If you’re a teacher, a student, or just someone who likes knowing things, start looking at different projections side-by-side. Use tools like "The True Size Of" website. It lets you drag countries around and watch them shrink or grow as they move across a Mercator projection. It’s a mind-blowing way to see how much we’ve been visually misled.

When you see a map in a news article or a textbook, ask yourself: what is this map trying to show me? If it’s a map about global population but it’s using a Mercator projection, it’s a bad map. It’s misleading you.

Actionable Steps for Better Mapping

- Check the Projection: Look at the bottom corner of any world map. If it doesn't say which projection it uses, be skeptical. For data visualization, look for "Equal-Area" or "Lambert."

- Use Digital Globes: If you need to see the world without any distortion, use a globe. Digital ones like Google Earth (which transitioned from a Mercator view to a 3D globe view for a reason) are the only way to see true proportions.

- Diversify Your Perspective: Hang an AuthaGraph or a Robinson projection on your wall instead of a standard Mercator. It’ll force your brain to stop seeing Europe and North America as the center of the physical world.

- Compare and Contrast: When looking at a country's size, look up its actual square mileage. Compare it to a country near the equator. For example, Brazil is actually larger than the contiguous United States, though many maps make it look smaller.

The world isn't what it looks like on paper. Embracing the "messiness" of an accurate proportional world map isn't just about geography; it's about seeing the world with a bit more humility and a lot more truth. We live on a beautiful, curved, complex rock. It’s time our maps started reflecting that reality instead of sticking to a 500-year-old shortcut.

To get a better handle on this, start by looking up the "Hobo-Dyer Projection." It’s a south-up map that is also equal-area. It will completely break your brain for about five minutes, but you’ll come out of it with a much better understanding of how arbitrary our standard maps really are. Keep exploring different projections like the Waterman Butterfly or the Dymaxion map by Buckminster Fuller. Each one offers a different "truth" about our planet. Change your map, change your mind.