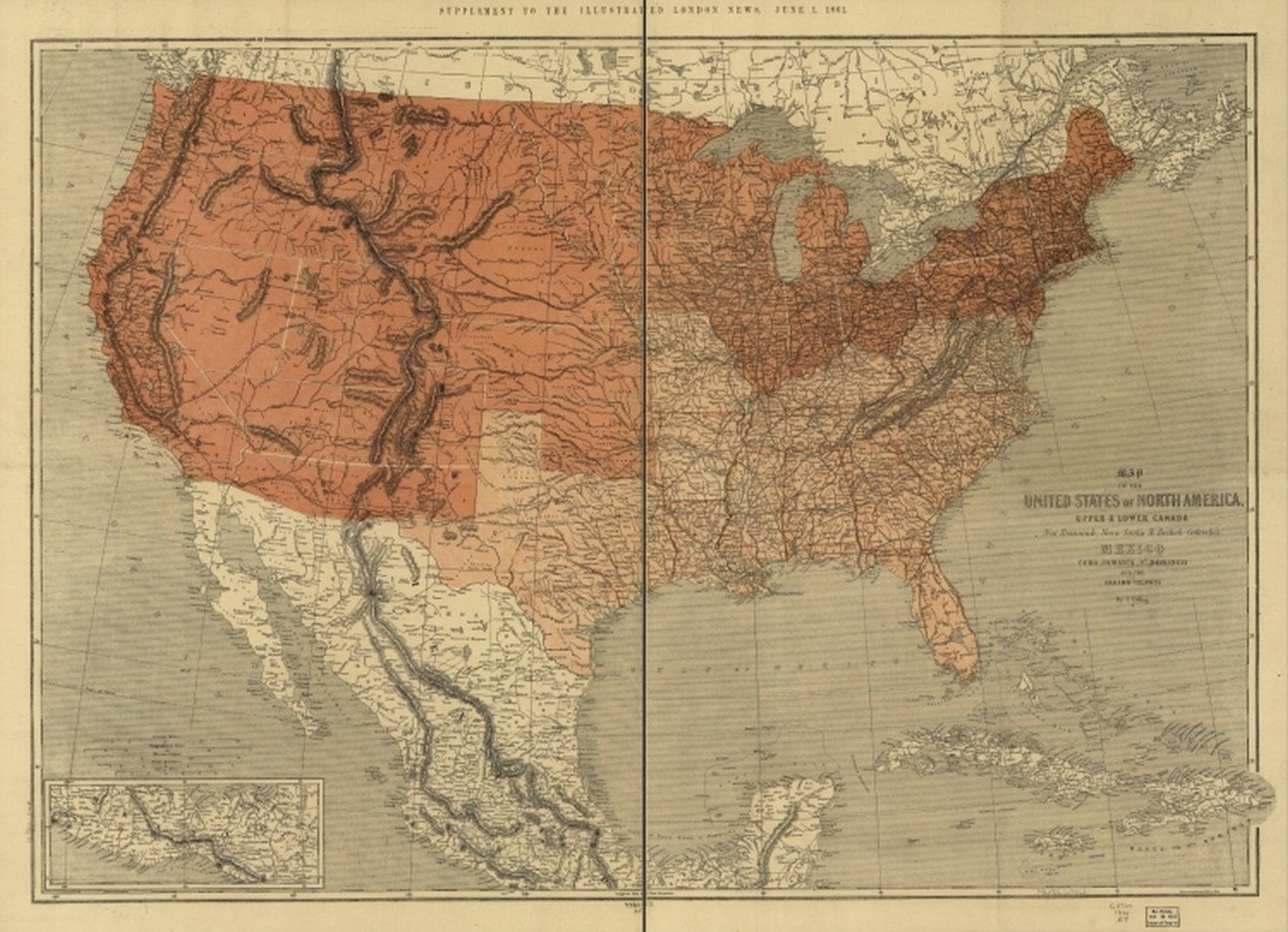

Look at an 1861 map of United States and you’ll see a country that is basically a ghost of itself. It’s haunting. You’ve got these jagged lines and "unorganized territories" that look nothing like the neat, rectangular states we memorize in grade school today. Honestly, if you want to understand why the American Civil War was so messy, you have to stop reading the dry textbooks and start staring at the cartography from that specific, desperate year.

Maps aren't just paper and ink. They're snapshots of power.

In 1861, the map was lying to people. Or, at least, it was trying to keep up with a reality that was shifting faster than the printers could handle. You had states like Kansas finally entering the Union in January, just as the Deep South was sprinting for the exit. It was a cartographic nightmare.

The messy reality of the 1861 map of United States

When you find an original 1861 map of United States, the first thing that hits you is the sheer emptiness of the West. It wasn't empty of people, obviously—Indigenous nations were there—but from a federal perspective, it was a massive "to-be-determined" zone. This mattered because the whole war was essentially a giant, bloody argument over who got to decide what happened in those blank spaces. Would they be slave-holding states or free soil?

The map was the scoreboard.

Take a look at the border states. That’s where the 1861 map gets really interesting and kinda confusing. Missouri, Kentucky, Maryland, and Delaware. On paper, they’re still there, shaded the same color as the North, but the reality on the ground was a fractured mess of guerrilla warfare and local militias. Cartographers like J.H. Colton or the folks at the Johnson’s Family Atlas had to figure out how to depict a nation that was literally tearing in half.

They usually stuck to the legalistic view. They showed the United States as one unit, often because the Northern-based publishers didn't want to give the Confederacy the dignity of a border.

Why the "Hog-and-Hominy" lines mattered

In 1861, mapping wasn't just about geography; it was about resources. The Union's War Department was obsessed with the details of the 1860 Census. They started overlaying that data onto maps. One of the most famous examples—and one that Abraham Lincoln supposedly obsessed over—was the map of slavery's distribution.

💡 You might also like: Wire brush for cleaning: What most people get wrong about choosing the right bristles

It was created by the U.S. Coast Survey.

It showed the density of the enslaved population. This wasn't just a political tool; it was a tactical one. By looking at an 1861 map of United States that included this demographic data, Lincoln could see exactly where the rebellion was strongest and where it was thin. He could see that in the mountainous regions of Western Virginia and Eastern Tennessee, the "slave density" was low.

That map literally helped create the state of West Virginia. It’s one of the few times in history where a map didn't just record a change—it caused one.

The cartographers who risked it all

Mapping in 1861 was a high-stakes game. You had guys like Orlando Poe and other topographical engineers who were essentially the "Google Maps" of their day, but with way more lead flying at them. They had to sketch out terrain in real-time.

A lot of the commercial maps you find from 1861 are actually based on older plates. Publishers were cheap. They’d take an 1859 plate, scratch in "West Virginia" (later in the war) or update a railroad line, and call it new. But the 1861 editions are special because they capture the "Status Quo Ante Bellum"—the way things were right before the fire.

The railroads are the most telling part.

If you trace the iron lines on an 1861 map of United States, you see the North’s massive advantage. It’s a spiderweb of connectivity. The South? It’s a few disjointed lines mostly designed to move cotton to ports. You can almost see the Union victory written in the infrastructure before the first shot was even fired at Fort Sumter.

📖 Related: Images of Thanksgiving Holiday: What Most People Get Wrong

Common misconceptions about 1861 cartography

People often think every map from 1861 shows the Confederate States of America as a separate country. They didn't. Most Northern publishers refused. If you find a map from 1861 that clearly delineates the "C.S.A." as a sovereign nation, you’ve likely found a rare Southern-printed map or a European one.

British and French mapmakers were much more "neutral." They were happy to draw a line between the North and South because they were hedging their bets on who would win. They wanted that Southern cotton, after all.

How to spot a fake or a reproduction

If you’re looking to buy an original 1861 map of United States, you have to be careful. The market is flooded with "aged" reprints. Real 1861 paper has a specific feel—it’s thin, almost like a high-quality vellum, and the ink usually has a bit of a "bite" into the page.

Check the folds.

Original maps were often folded into small pocket guides for travelers or soldiers. Look for wear along those fold lines. If the "aging" is perfectly uniform across the whole page, it’s probably a modern tea-stained reproduction. Also, look at the coloring. In 1861, color was often applied by hand using stencils. It’s not perfect. You’ll see little overlaps and "mistakes" that a digital printer would never make.

The value of the 1861 Coast Survey maps

The most valuable maps from this era aren't usually the pretty ones you hang in a study. They’re the functional ones. The U.S. Coast Survey maps of 1861 are incredibly detailed. They were used for naval blockades. They show every inlet, every sandbar, and every fort.

These maps were the high-tech tech of 1861.

👉 See also: Why Everyone Is Still Obsessing Over Maybelline SuperStay Skin Tint

Holding one feels different. You’re holding the actual data that admirals used to choke off the Southern economy. It’s visceral.

What an 1861 map of United States teaches us today

We tend to think of the past as settled. We look at a modern map and see solid lines. But the 1861 map reminds us that everything is fluid.

The "Territory of New Mexico" on an 1861 map was massive. It included what is now Arizona. The "Washington Territory" reached all the way over to modern-day Idaho and Montana. It was a world in flux.

When you study these maps, you realize the United States wasn't a finished project. It was an experiment that was failing. Seeing the "unorganized" bits of the country helps you understand the sheer scale of the chaos. It wasn't just a war between two sides; it was a fight over the future of an entire continent that hadn't even been fully drawn yet.

Actionable steps for collectors and history buffs

If you're serious about diving into 1861 cartography, don't just look at the big national maps. The real gold is in the county maps.

- Visit the Library of Congress Digital Collection. They have high-resolution scans of the 1861 "Civil War Maps" that allow you to zoom in until you can see individual farmhouses. It's a massive, free resource that most people ignore.

- Search for "Pocket Maps." These were the 19th-century version of a GPS. They usually come in a small leather or cloth case. They’re more durable than wall maps and often have more interesting annotations from the people who actually used them.

- Check the Railroads. If you want to verify a map's date, look at the rail lines in Illinois and Ohio. By 1861, these were exploding in growth. Compare them to an 1858 map; if they're identical, the publisher was lazy and you're looking at old data.

- Look for the "Confederate" mark. As mentioned, these are rare. If you find a map actually printed in Richmond or Charleston in 1861, get it appraised immediately. The Confederate printing industry struggled with paper shortages almost immediately, making their output scarce and highly collectible.

- Study the "Vignettes." Many 1861 maps have little illustrations in the corners—steamships, "heroic" imagery, or statistical charts. These tell you more about the cultural mindset of the time than the geography does. They show you what the people of 1861 valued.

Maps are just stories we tell about where we are. In 1861, that story was a tragedy, but the maps themselves are beautiful, complex, and surprisingly honest if you know how to read between the lines. They show a nation that was lost, trying to find its way back to being a single, cohesive unit.