April 1917 changed everything. Before that, the United States was basically a neutral bystander watching Europe tear itself apart. Then, the Zimmerman Telegram and unrestricted submarine warfare pushed Woodrow Wilson over the edge. Suddenly, the country had to figure out how to turn a tiny frontier constabulary into a massive global fighting force. American soldiers leaving for WW1 didn't just walk onto ships; they were part of a massive, messy, and deeply emotional upheaval that reshaped every town in the country.

Most people imagine a clean, sepia-toned movie scene. You know the one: handsome boys in crisp uniforms waving from trains while girls throw roses. It happened, sure. But the reality was way louder and more confusing. Imagine thousands of guys who had never left their county suddenly being shoved into "Cantonments"—massive, rapidly built wooden cities like Camp Funston in Kansas or Camp Devens in Massachusetts. These places were built so fast the wood was often still green.

The Sudden Goodbye: Drafting a Nation

The Selective Service Act of 1917 was a shock. It wasn't like the Civil War where you could pay someone to take your place. Rich, poor, urban, rural—everyone was in the mix. By the time the war ended, about 2.8 million men were drafted. When you talk about American soldiers leaving for WW1, you have to realize that for many, the "leaving" started at a local draft board office or a dusty railway platform in a town of 400 people.

It was fast. One week you’re milking cows or filing paperwork in a Manhattan office, the next you’re standing in your underwear in a cold room being poked by an Army doctor.

History books often skip the logistics of the departure. It wasn't just the soldiers leaving; it was the resources. The "Great Departure" meant the economy shifted overnight. Families didn't just lose a son; they lost the primary breadwinner or the strongest hand on the farm. If you look at the archives from the National World War I Museum and Memorial, you see letters where the tone isn't always "patriotic glory." Often, it’s just: "Who is going to fix the roof now that I'm gone?"

Life in the Cantonments

Before they could even see the Atlantic, these men had to become "Doughboys." Nobody really agrees on where that nickname came from—maybe the pipe clay used to clean belts, maybe the shape of their buttons—but it stuck.

👉 See also: The Gospel of Matthew: What Most People Get Wrong About the First Book of the New Testament

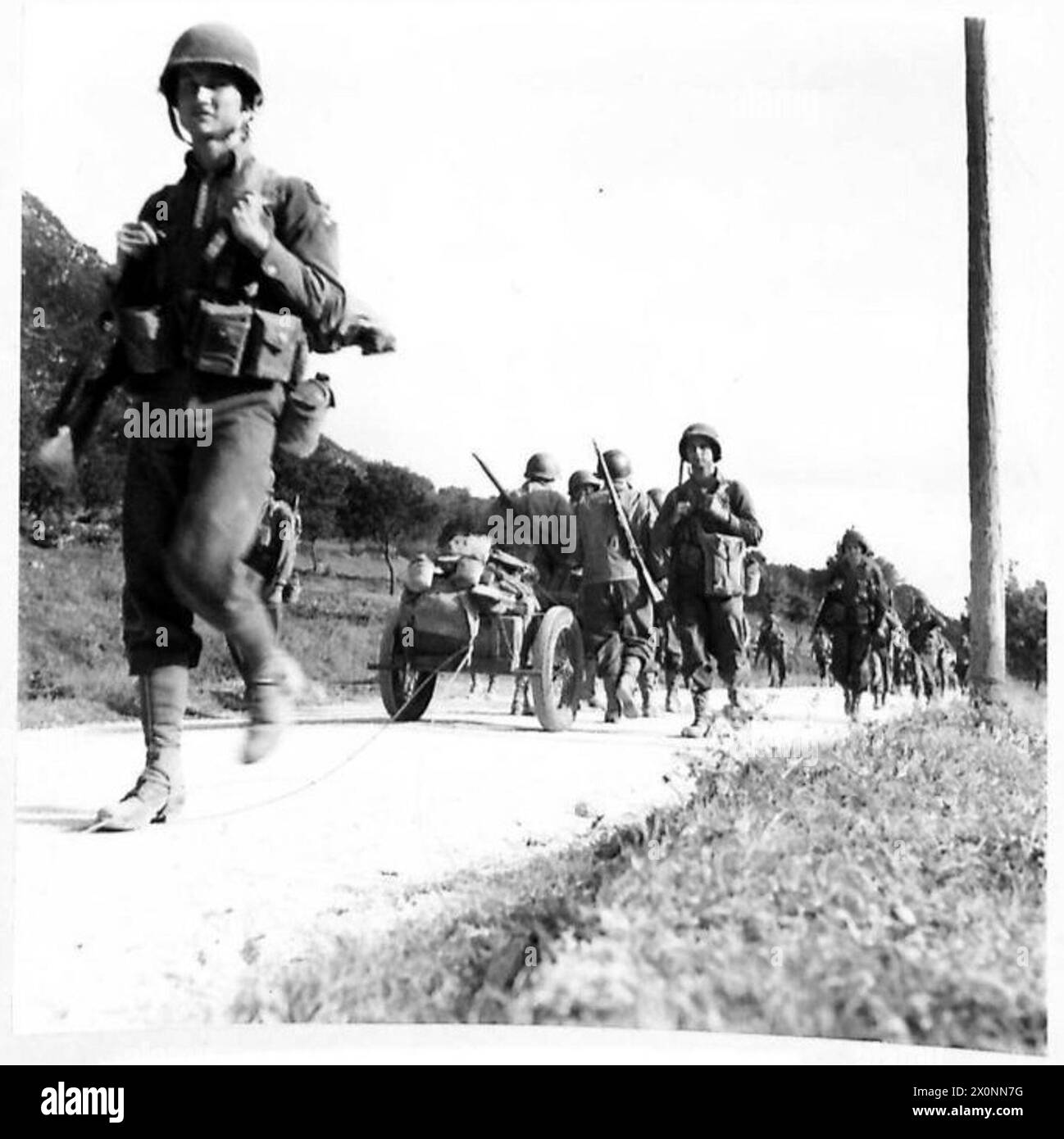

Training was a disaster at first. There weren't enough rifles. Seriously. In 1917, some American soldiers leaving for WW1 were actually drilling with wooden poles because the Springfield and Enfield rifles hadn't reached the camps yet. Imagine the psychological shift of being told you’re going to save the world, then being handed a broomstick and told to "march in a straight line."

It was also crowded. This led to one of the darkest parts of the departure story: the 1918 flu. Because the Army moved people from every corner of the country into cramped barracks, it created a petri dish. Many soldiers who "left" for the war never even made it to the docks in Hoboken or Newport News; they died in a wooden bunk in New Jersey or Kansas.

The Hoboken Gateway and the Voyage Over

If you were a soldier on the East Coast, your final memory of America was probably Hoboken, New Jersey. This was the "Port of Embarkation." General John J. Pershing famously promised "Heaven, Hell, or Hoboken by Christmas." It became the funnel for the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF).

The sheer scale was insane.

- Over 2 million men passed through.

- The Leviathan, a seized German liner (formerly the Vaterland), could carry 14,000 troops at a time.

- Men were packed into "standee" bunks stacked five or six high.

- The smell was a mix of coal smoke, salt air, and thousands of unwashed bodies.

The Secret Departures

While we love the images of parades, a lot of American soldiers leaving for WW1 actually left under the cover of darkness. Why? U-boats. The German Navy was hunting for troop transports. To keep things safe, many ships slipped out of New York Harbor at 2:00 AM with all lights extinguished.

✨ Don't miss: God Willing and the Creek Don't Rise: The True Story Behind the Phrase Most People Get Wrong

Soldiers weren't allowed to tell their families exactly when they were sailing. You’d get a final postcard that said "Safe Arrival" that was mailed only after they reached Brest or Saint-Nazaire in France. This created a weird, suspended state of grief for the families left behind. Was he at sea? Was he already in a trench? Nobody knew for weeks.

Racial Tensions and the Departure

We can't talk about this without mentioning that the Army was strictly segregated. For Black soldiers, like those in the famous 369th Infantry Regiment (the Harlem Hellfighters), leaving for the war was even more complex. They were fighting for a "democracy" that didn't fully recognize their own rights at home.

When the 369th left, they weren't even allowed to participate in the "Rainbow Division" farewell parade because "black is not a color in the rainbow." They had their own send-off later, marching down Fifth Avenue to the sound of James Reese Europe’s jazz band. For these men, leaving America was a chance to prove their worth on a global stage, even if their own country was hesitant to give them a seat at the table.

The Psychological Weight of the "Big Trip"

For a kid from a small town in 1917, crossing the Atlantic was like going to Mars. Most people never traveled more than 50 miles from their birthplace. Suddenly, they were on a massive steel ship, seeing the horizon for the first time.

The diary of a soldier named Edward Lukens mentions the "monotony and the majesty" of the ocean. You’re terrified of a submarine hitting you, but you’re also bored out of your mind eating "slum" (a watery beef stew) and trying not to get seasick.

🔗 Read more: Kiko Japanese Restaurant Plantation: Why This Local Spot Still Wins the Sushi Game

What People Get Wrong About the Send-off

There’s this myth that everyone was 100% gung-ho. While patriotism was high, there was also a lot of desertion and draft evasion. In some rural areas, particularly in the South and the Ozarks, federal agents had to go in and find men who simply refused to leave. The "unanimous" support for the war is a bit of a historical polish.

Also, the uniforms. People think they looked sharp. In reality, the early wool uniforms were itchy, poorly fitted, and hot. Many soldiers looked more like they were wearing potato sacks than military tunics when they first boarded those trains.

Actionable Ways to Trace This History

If you have a relative who was one of those American soldiers leaving for WW1, don't just guess what happened to them. The paper trail is actually pretty incredible if you know where to look.

- Check the Transport Service Passenger Lists: The National Archives has digitized lists of almost every soldier who boarded a ship. It will tell you the name of the ship (like the SS Baltic or RMS Olympic), the date they left, and exactly which pier they sailed from.

- Look for "Bird's Eye" Camp Maps: Most soldiers trained at one of 32 major cantonments. You can find high-res maps of these camps online. If your Great-Grandpa was at Camp Logan, you can see exactly where his barracks stood.

- Read the "Stars and Stripes" Archives: The military newspaper started in France but covered the arrival of new troops. It gives a great "boots on the ground" feel for what those first days in Europe were like after the long boat ride.

- Visit Hoboken's Historical Markers: If you're ever in the NYC area, walk the Hoboken waterfront. There are markers near the PATH station that show where the piers were. Standing there makes the scale of 2 million men leaving feel much more real.

The departure wasn't just a military movement. It was a cultural pivot point. When those ships pulled away from the docks in New Jersey and Virginia, the old, isolated America stayed on the shore. The country that returned 18 months later was a global superpower, whether it was ready for that responsibility or not.

The soldiers who left were mostly just kids who wanted to see "Paree" and get the job done. They carried the weight of a changing world in their canvas haversacks. Knowing the grit and the chaos of their departure makes their service feel a lot more human than any bronze statue ever could.