It starts with a pair of sneakers. Specifically, the "LeBron 20s" that Jin Wang thinks will magically solve his social status at a generic suburban high school. If you've sat through all the American Born Chinese episodes, you know that the show isn't actually about the shoes. It isn't even really about the high school. It’s a weird, vibrating collision between a 16-year-old’s awkward social life and a literal war between gods in the Heavenly Realm.

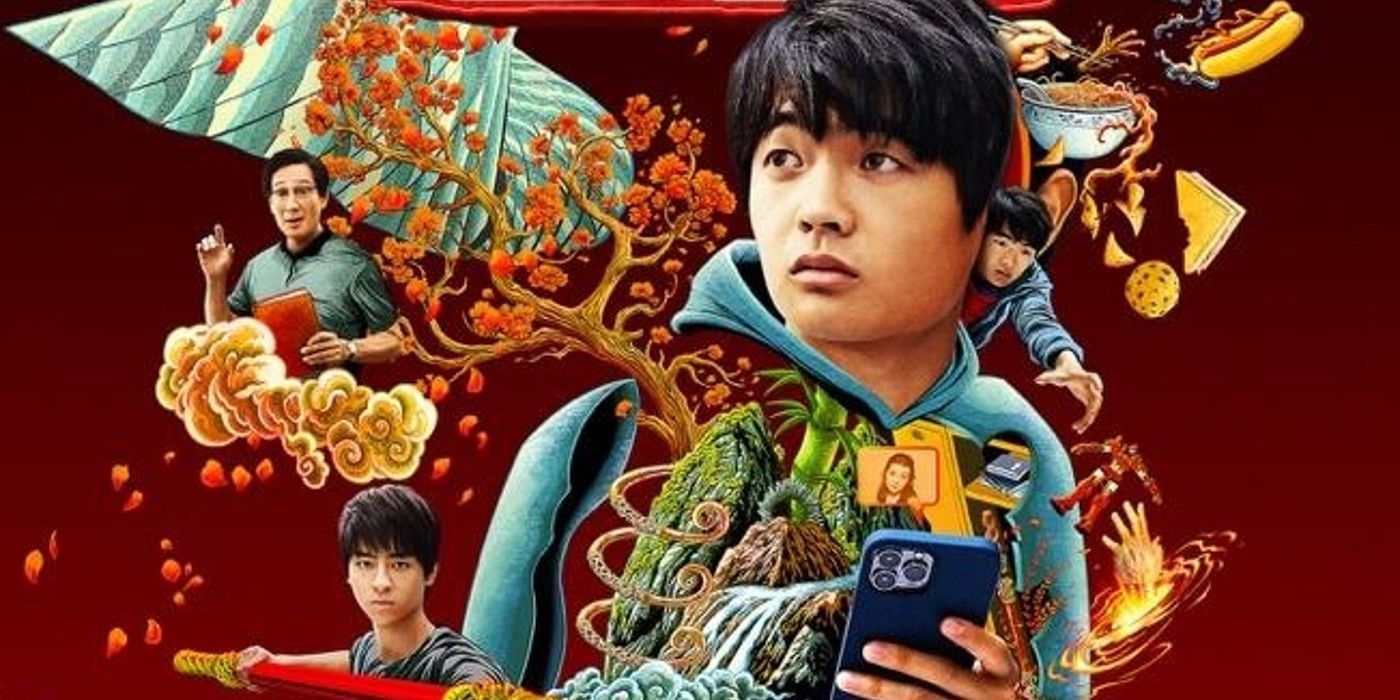

Disney+ dropped the entire eight-episode run at once. Some people binged it in a night; others took their time to digest the weirdly specific cultural trauma baked into the script. Honestly, it’s a lot to process. You’ve got Gene Luen Yang’s legendary graphic novel being remixed by Kelvin Yu, with Michelle Yeoh and Ke Huy Quan fresh off their Oscar wins. It’s a heavy-hitter lineup for a show that, on the surface, looks like a Disney Channel original with a massive VFX budget.

The pacing is frantic. One minute we’re watching Jin deal with a racist meme at school, and the next, a monkey-king-turned-god is crashing through a cafeteria ceiling. It’s jarring. It’s also exactly what being a second-generation immigrant feels like—living in two completely different universes that keep smashing into each other at the worst possible times.

The Breakdown of American Born Chinese Episodes

The season is tight. Eight chapters. No filler.

Episode 1, "What Guy Are You," sets the stakes. Jin Wang is just trying to be "normal," which in his world means being invisible enough to fit in but cool enough to get on the soccer team. Enter Wei-Chen. He’s the new kid, but he’s not just "from China." He’s the son of Sun Wukong, the Monkey King. The episode establishes the central tension: Jin wants to run away from his heritage, while Wei-Chen is literally on a quest fueled by it.

As we move into Episode 2, "A Chameleon," the show starts to flex its mythological muscles. We see the introduction of Guanyin, played by Michelle Yeoh. She’s the Goddess of Mercy, but she’s also a suburban auntie who enjoys IKEA furniture. It’s a brilliant bit of characterization. The show treats the divine and the mundane with the same level of casualness.

Why Episode 4 Is the Secret Heart of the Show

If you ask most fans which of the American Born Chinese episodes stands out, they’ll point to "Make a Splash." It’s a flashback. We leave the high school drama behind and go full wuxia. It tells the backstory of Sun Wukong and Niu Mowang (the Bull Demon).

📖 Related: Why Grand Funk’s Bad Time is Secretly the Best Pop Song of the 1970s

The production design here is insane. It looks like a high-end Chinese period drama, dripping with gold and clouds. It explains the rift between the two friends—one who wants to change the system from the inside and one who wants to burn it down. It’s a classic "Prestige TV" move to break the format mid-season, and it works because it gives the stakes actual weight. Without this episode, the finale wouldn't land. You need to see the brotherhood break to care about the kids trying to fix it.

Dealing with the "Beyond Help" Controversy

We have to talk about Freddy Wong. Ke Huy Quan plays Jamie Yao, an actor who played a stereotypical character named Freddy Wong in a 90s sitcom called "Beyond Help."

Throughout the American Born Chinese episodes, we see clips of this fake show. It’s painful to watch. The exaggerated accent, the pratfalls, the "What’s he doing here?" catchphrase. Some critics felt it was too on-the-nose. But for anyone who grew up watching Long Duk Dong or similar caricatures, it’s deeply cathartic.

In Episode 7, "Beyond Help," Jamie Yao gives a monologue that basically serves as the mission statement for the entire series. He talks about wanting to be the hero, not the punchline. It’s a meta-moment. Ke Huy Quan is essentially speaking about his own career hiatus and the industry's historical treatment of Asian men. It’s heavy stuff for a "family" show.

The Cultural Architecture of the Series

This isn't just a retelling of Journey to the West. It’s a critique of it.

- The Monkey King (Daniel Wu): He’s a dad now. He’s worried. He’s strict. He’s every immigrant parent who doesn't know how to talk to his kid.

- The Fourth Scroll: The MacGuffin of the season. It represents a power that can stop the uprising in Heaven, but it’s revealed to be something much more internal and human than a magical piece of paper.

- The Soccer Team: A microcosm of social hierarchy. Jin’s struggle to belong there mirrors the Monkey King’s struggle to be respected by the Jade Emperor.

The show uses these parallels constantly. When Jin betrays Wei-Chen to stay "cool," it mirrors the cosmic betrayals happening in the clouds. It’s smart writing. It assumes the audience is capable of tracking two disparate storylines that eventually merge into a singular fight for identity.

👉 See also: Why La Mera Mera Radio is Actually Dominating Local Airwaves Right Now

Action and Choreography: Does it Hold Up?

Let’s be real. If the fights are bad, the show fails.

Peng Zhang, who worked on Shang-Chi, handled the stunts. The fight in the school hallway in the pilot is a standout. It uses the environment—lockers, backpacks, linoleum floors—to create a rhythmic, Jackie Chan-style sequence. It’s not just punching; it’s storytelling through movement.

By the time we get to the finale, Episode 8, "The Fourth Scroll," the scale explodes. We’re talking a high school gate becoming a portal to another dimension. The VFX can occasionally look a little "TV-budget," especially when things get heavy on the CGI clouds, but the physical acting usually carries it. Seeing Michelle Yeoh fight with a rolled-up poster or a grocery bag is a reminder that she’s the GOAT for a reason.

Common Misconceptions About the Ending

A lot of people finished the eighth episode and felt confused. Wait, that’s it? The ending is a massive cliffhanger. Jin’s parents are gone. Princess Iron Fan is looming. Wei-Chen is back in the celestial realm. It was clearly designed for a Season 2 that Disney eventually canceled. This has left the American Born Chinese episodes in a weird limbo. It’s a complete emotional arc for Jin, but an incomplete narrative arc for the world-building.

Despite the cancellation, the show remains a "must-watch" for its technical ambition alone. It’s rare to see a studio spend this much money on a story that is so unapologetically specific to the Chinese-American experience. It doesn't stop to explain every reference. It assumes you know what a jianbing is or why certain honorifics matter.

How to Watch for the Best Experience

Don't just have this on in the background while you're scrolling on your phone. You'll miss the subtitles, sure, but you'll also miss the visual language.

✨ Don't miss: Why Love Island Season 7 Episode 23 Still Feels Like a Fever Dream

- Watch the original "Beyond Help" clips closely. They evolve. The way they are framed changes as Jin's perception of himself changes.

- Pay attention to the color palette. The human world is washed out, slightly beige and boring. The Heavenly Realm is oversaturated. When the two begin to bleed together in the later episodes, the colors start to mix.

- Track the "Fourth Scroll" clues. The show leaves breadcrumbs about what the scroll actually is as early as the third episode. It’s not a plot hole; it’s a payoff.

The series is currently streaming on Disney+ and occasionally appears on Hulu depending on your bundle. Even though we might never get a second season, the eight episodes we have are a masterclass in adaptation. They took a "unfilmable" graphic novel and turned it into something that feels modern, urgent, and deeply personal.

If you're looking for a show that balances high-octane wuxia action with the crushing reality of trying to find a seat at the lunch table, this is it. It’s messy, it’s loud, and it’s heart-wrenching. Just like being a teenager.

The real value of these episodes isn't in the resolution of the "Great War" in heaven. It’s in the moment Jin Wang finally looks in the mirror and stops wishing he was someone else. That’s the real hero’s journey. Everything else—the flying, the magic staves, the goddesses—is just window dressing for the hardest battle of all: liking yourself.

For those wanting to dive deeper into the lore, checking out the original 16th-century novel Journey to the West provides an entirely different layer of appreciation for the creative liberties the show takes. You'll see how they flipped the script on characters like the Dragon King or the Jade Emperor, making them feel like bureaucratic middle managers rather than distant deities. It’s a clever spin on ancient mythology that makes the show feel fresh even if you’ve heard these stories a thousand times before.

The takeaway is simple. Watch it for the action, stay for the characters, and don't be surprised if you find yourself feeling a little more seen by the end of it.