Frédérick Raynal probably didn’t realize he was about to change how we feel fear in front of a monitor. It was the early nineties. Most games were flat. You moved a sprite left, you moved it right, maybe you jumped over a pixelated pit. Then Infogrames released Alone in the Dark 1992, and suddenly, the walls felt like they were closing in.

It was janky. It was clunky. Honestly, by today's standards, Edward Carnby moves like he’s trying to navigate a bathtub filled with molasses. But back then? It was a revolution in geometry.

The Birth of Survival Horror (Before It Had a Name)

Most people give all the credit to Capcom. They think Resident Evil dropped out of the sky in 1996 as a fully formed genre. Not true. Shinji Mikami has been pretty open about the fact that without the French developers at Infogrames, the Spencer Mansion might never have existed. Alone in the Dark 1992 gave us the blueprint: fixed camera angles, a limited inventory, and that crushing sense of "I have three bullets and there are four things in the hallway."

It’s easy to look at the low-polygon models now and laugh. Carnby looks like a collection of sharpened pencils. But in 1992, seeing a 3D character move through a hand-painted, static background was mind-blowing. It created a cinematic perspective that 2D games just couldn't touch. You'd walk into a room, the camera would shift to a high corner, and you’d see a shadow move.

The fear wasn't about the graphics. It was about what you couldn't see.

Derceto Manor is the Real Main Character

The game takes place in Louisiana. Derceto Manor is this sprawling, Cthulhu-inspired death trap. You choose between Edward Carnby or Emily Hartwood. They’re both there to investigate the apparent suicide of Jeremy Hartwood, but the house has other plans.

What made Alone in the Dark 1992 so special—and frankly, what modern games often mess up—was the sheer variety of ways to die. You don't just get eaten by a zombie. You can fall through a weak floorboard. You can read a book that literally drives you insane and ends the game. You can get jumped by a bird-monster crashing through a window in the first thirty seconds if you don't push a heavy wardrobe in front of it.

Mechanics That Rewired Our Brains

The game forced you to think. It wasn't a shooter. It was a puzzle game where the penalty for a wrong answer was a gruesome death animation. You spent half your time shoving furniture against doors.

That’s a mechanic we don't see enough of anymore. The environment wasn't just a backdrop; it was a tool. You found a heavy pot? You used it to weight down a pressure plate. You found an old mirror? You used it to distract a statue that would otherwise kill you. It felt tactile in a way that contemporary games like Wolfenstein 3D didn't.

The Lovecraftian Soul of the Game

While the game takes its name from a generic-sounding horror trope, its heart belongs to H.P. Lovecraft. We’re talking Deep Ones, Cthulhu references, and the Necronomicon. It didn't just borrow the monsters; it borrowed the atmosphere of inevitable doom.

The writing was surprisingly dense. You’d find diaries and notes scattered around the house. Reading them wasn't just flavor text. It was survival. If you didn't read the note about the cigar, you wouldn't know how to deal with the supernatural smoke in the library. Information was a resource just as valuable as health kits.

Why the Graphics Worked (Even Though They Were Basic)

The tech was called "polygonal 3D." In 1992, this was cutting edge. By using 3D models on 2D backgrounds, the developers saved a massive amount of processing power. This allowed them to put incredible detail into the rooms—the rugs, the paintings, the creepy grandfather clocks—while the characters remained fluid.

📖 Related: Why Your Best Skating On Ice Game Isn't What You Think

Well, "fluid" is a strong word.

The movement used "tank controls." You press up to move forward, regardless of where the camera is. It’s a polarizing system. Some people hate it. They say it’s unintuitive. But in a horror context? It’s perfect. It makes you feel clumsy. It makes you panic when a monster is charging and you’re struggling to turn around. It adds a layer of physical anxiety that fits the narrative of a normal person trapped in a nightmare.

The Legacy of Frédérick Raynal

Raynal is a bit of a legend in the industry, though he doesn't get the same household-name recognition as Kojima or Miyamoto. He pushed for a game that wasn't just about killing. He wanted a game about escaping.

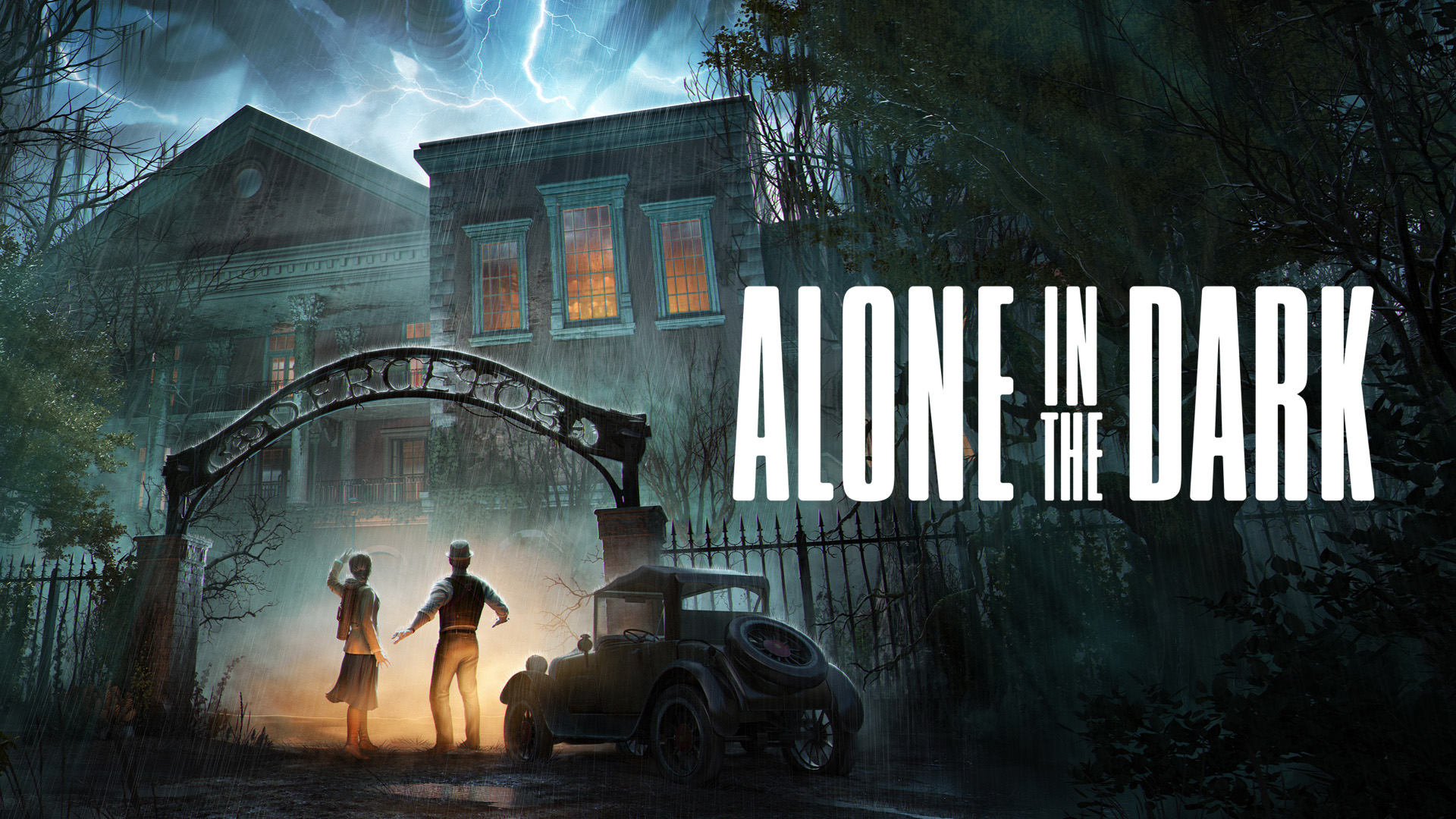

After the first game, there were sequels, sure. Alone in the Dark 2 and 3 went a bit more "action-heavy," and honestly, they lost some of that eerie magic. Then came the 2008 reboot, which was... ambitious, let's say. And the recent 2024 reimagining with David Harbour and Jodie Comer. They all try to capture that Derceto vibe, but there’s something about the 1992 original that feels more "pure."

It was a small team. They were experimenting. There were no focus groups telling them to make the combat easier or the puzzles more obvious.

Common Misconceptions About the 1992 Version

It’s just a Resident Evil clone.

Absolutely backwards. Resident Evil is an Alone in the Dark clone. Capcom’s original pitch was a remake of their own game Sweet Home, but once they saw what Raynal had done with 3D space, they pivoted.The game is impossible without a guide.

It’s hard, but it’s fair. Most deaths are a result of rushing. If you take your time, search every corner, and actually read the documents, the logic holds up.It only works on DOS.

While it was a PC staple, it actually saw a release on the 3DO (which looked slightly better) and even Mac. Today, you can grab it on GOG or Steam for a couple of bucks, and it runs fine on modern hardware through DOSBox.👉 See also: South Park: The Fractured But Whole is Still the Best Superhero Satire Ever Made

How to Play It Today Without Losing Your Mind

If you're going to dive back into Alone in the Dark 1992, you need to adjust your expectations. Don't play it like a modern third-person shooter. Play it like an interactive ghost story.

- Save often. In different slots. You can soft-lock yourself or just die instantly from a trap you didn't see coming.

- Check the floor. Traps are everywhere.

- Don't fight everything. Sometimes the best strategy is just to run to the next room and shut the door.

- Examine everything in your inventory. Items can be opened, read, or combined.

The game is a piece of history. It’s the bridge between the text adventures of the 80s and the cinematic horror of the 2000s. It’s short, too. You can beat it in about two to three hours once you know what you’re doing.

Moving Forward with the Franchise

If you’ve played the original and want more, don't just jump to the sequels. Look at the games it inspired.

Check out Silent Hill for the psychological evolution of these ideas. Look at Signalis for a modern take on the limited inventory and fixed-camera dread. But always come back to the source. The 1992 classic is where the darkness first started feeling lonely.

To get the most out of your retro gaming experience, try playing the original DOS version with the sound turned up and the lights turned down. Ignore the remake's flashy graphics for a night. Experience the clunky, polygonal tension that defined a generation. Search for the "Alone in the Dark Anthology" on digital storefronts to get the complete original trilogy, as the first game's context is best understood alongside its immediate, more action-oriented successors. Check the community patches on PCGamingWiki to ensure the frame rate doesn't break the physics on modern CPUs. Once you finish the game, look up the "making of" interviews with Frédérick Raynal to see the sketches of the original monsters; the hand-drawn concept art is often scarier than the polygons themselves. For those interested in the evolution of the genre, compare the mansion layout of Derceto to Resident Evil's Spencer Mansion to see exactly which rooms and puzzles were "borrowed." This provides a masterclass in level design history.