Ever wonder why "Bed Bath & Beyond" sticks in your head while "Sheets, Towels, and Other Stuff" just… doesn't? It’s not just the inventory. It’s the sound. Specifically, it’s that repetitive "B" sound hammering away at your subconscious. When we ask what does an alliteration do, we aren’t just talking about a dry poetic device from a 10th-grade English syllabus. We’re talking about a psychological hack that bridges the gap between seeing words and actually feeling them. It’s a rhythmic pulse.

Words have weight.

💡 You might also like: 4 to 9 is how many hours? The Answer Depends on Your Perspective

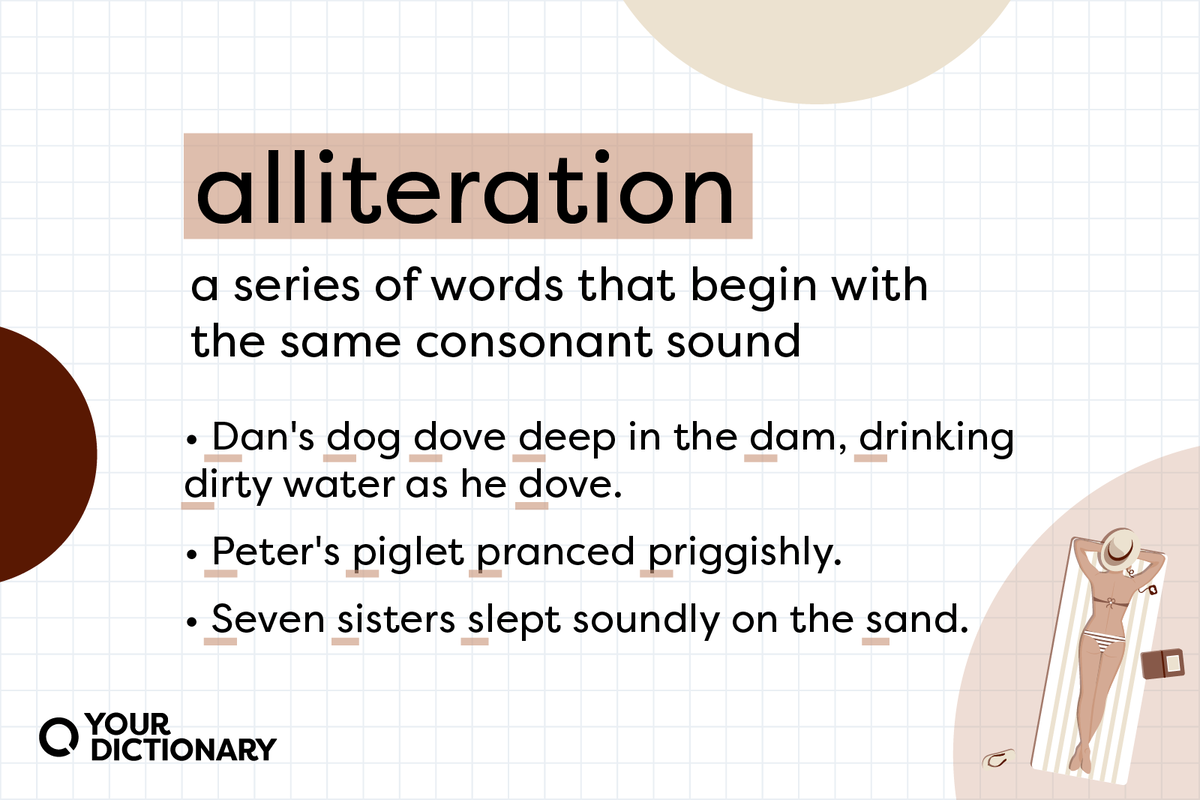

When you repeat the same initial consonant sound in a series of words, you’re creating a musical hook without needing a guitar. It’s a "brain tickle." Most people think alliteration is just for Dr. Seuss or tongue twisters about Peter Piper and his peppers. Honestly, though? It’s everywhere. It’s in the brands you buy, the way politicians try to convince you of a "New Normal," and the reasons why certain movie titles feel "right."

The Acoustic Glue: Why Our Brains Love Repetition

The primary thing an alliteration does is create memory. Our brains are hardwired to recognize patterns. According to cognitive psychologists, phonological loop processing helps us store verbal information more efficiently when there’s a recurring sound. Think of it as a mental filing system. If the sounds match, the brain files them together.

It’s mnemonic.

If I say "The slippery snake slithered," you don't just see a reptile; you hear the hiss. That "S" sound mimics the actual noise of the subject. This is called onomatopoeic alliteration, and it’s a powerhouse for sensory writing. It forces the reader to slow down. Or speed up. It controls the tempo of the internal monologue. If you use hard "P" or "K" sounds, the sentence feels percussive and aggressive. Switch to "L" or "W" sounds, and suddenly everything feels fluid and airy.

Breaking Down the "Linguistic Vibe"

What does an alliteration do to the mood of a piece? It acts as an emotional thermometer. Let’s look at some real-world vibes:

- The Power Punch: Think of the "M" in "Marvelous Mrs. Maisel" or the "D" in "Dunkin' Donuts." These hard, repeated starts provide a sense of confidence and establishment. They feel finished.

- The Soothing Slur: In poetry, like Robert Frost’s "Saying 'Snow,'" the repetition of softer consonants creates a hushed atmosphere. It pulls the reader into a quiet space.

- The Comedic Click: Alliteration is often funny because it’s inherently "extra." "The bumbling, bickering brothers" sounds more ridiculous than "The clumsy siblings who fought." The repetition highlights the absurdity.

Sometimes, writers use it to link two opposing ideas. By giving them the same starting sound, you trick the brain into thinking they belong together. It creates a false sense of logic that is incredibly persuasive in marketing and speechwriting.

Not Just for Poets: Alliteration in the Real World

Look at "PayPal," "Coca-Cola," "Krispy Kreme," and "Best Buy." These aren't accidents. Marketing teams spend millions of dollars because they know that alliteration increases "fluency." Fluency is the ease with which we process information. When something is easy to process, we tend to trust it more. We think it’s truer. It’s a weird glitch in human psychology, but it’s real.

In 1940, Winston Churchill didn't just talk about struggle; he talked about "blood, toil, tears, and sweat." While not all those words start with the same letter, the "T" sounds in "toil" and "tears" provide that rhythmic anchor. It made the hardship sound noble rather than just miserable.

The Fine Line Between "Catchy" and "Cringe"

Here is where most people get it wrong. They think if two words starting with "B" are good, then ten words starting with "B" must be amazing.

No. Stop.

Overdoing it makes you sound like a cartoon character. When alliteration becomes too obvious, it loses its power. It starts to feel like a gimmick. The goal is "stealth alliteration." You want the reader to feel the rhythm without necessarily noticing the technique. Subtle pairs like "tried and true" or "fast and furious" work because they feel natural. If you write "The basically brilliant baker bought big bananas," it's annoying. It draws too much attention to the writer's effort and takes the reader out of the story.

Why It Works for SEO and Digital Content

If you're writing for the web in 2026, you're fighting for attention spans that are basically non-existent. What does an alliteration do for a digital headline? It stops the scroll. A rhythmic headline is easier to scan. It feels "snappy." When a user sees a title that has a nice ring to it, they are statistically more likely to click because the brain anticipates a satisfying reading experience.

It's about "Echoic Memory." This is the very brief mental echo we hear after a sound is made. Alliteration exploits this by re-triggering the echo before it fades. It keeps the phrase alive in the mind for a few milliseconds longer than a standard phrase. In the world of "Google Discover," where you have half a second to make an impression, those milliseconds are everything.

How to Use Alliteration Without Looking Like a Bot

If you want to actually improve your writing, you have to be intentional. Don't just throw matching letters together.

First, identify the "heart" of your sentence. What's the main action? If you're writing about a fast car, use "F," "S," or "T" sounds. "The tires tore through the track." The "T" sound is sharp. It sounds like rubber hitting asphalt.

Second, vary the placement. It doesn't always have to be the very next word. "The cat sat quietly on the couch" is alliteration even with "sat quietly" in the middle. This is called "internal alliteration" or "loose alliteration." It’s much more sophisticated. It creates a "callback" effect rather than a "hammer" effect.

Third, watch your "plosives." Words starting with B, P, T, D, K, and G are plosives. They involve a burst of air. Using them in alliteration creates a lot of energy. Use them when you want to sound authoritative or excited. If you want to sound relaxed, stick to "fricatives" like F, S, V, and Z.

Common Misconceptions: Alliteration vs. Consonance vs. Assonance

People mix these up constantly.

Alliteration is specifically about the start of the word (or the stressed syllable). "The lush lawn" is alliteration.

Consonance is the repetition of consonant sounds anywhere in the words. "The block knocked back." That "ck" sound is everywhere. It’s crunchy. It creates a different kind of texture.

Assonance is the repetition of vowel sounds. "The rain in Spain stays mainly in the plain." This creates a melodic, rhyming quality within a sentence.

When people ask what does an alliteration do, they are usually looking for the psychological impact of the start of the word, which is the most aggressive form of sound-matching. It’s the "first impression" of the word.

Actionable Steps for Better Writing

- Read Out Loud: This is the only way to catch bad alliteration. If you stumble over the words or feel like a tongue-twister is forming, you’ve gone too far. If it flows like a song, you’ve nailed it.

- Audit Your Headlines: Look at your last three social media posts or articles. Could a quick "sound-match" make them more memorable? Instead of "Great Tips for Gardeners," try "Green Guidelines for Gardeners." It's stickier.

- Use It for Emphasis: Save alliteration for the most important point of your paragraph. Use it to "bold" the idea with sound.

- Avoid Accidental Alliteration: Sometimes we repeat sounds by mistake, and it sounds clunky. "He had his hat." It's repetitive but not in a cool way. It just sounds stuttery. If it doesn't serve a purpose, change a word.

Ultimately, alliteration is a tool for connection. It’s a way to make your prose feel less like a series of instructions and more like a human voice. It provides a pulse to the page. When used with a bit of restraint and a lot of intent, it transforms "information" into "influence."

Start by looking at your favorite song lyrics. You'll see it everywhere. Rappers are the modern masters of this—they know that the "What" of the story matters less than the "How" of the sound. Once you start hearing the patterns, you can't un-hear them. And once you start writing them, people won't be able to stop reading you.