Music is weird. Usually, a songwriter owns their work forever, but Bob Dylan famously handed the keys to the kingdom over to Jimi Hendrix. When you hear all along the watchtower live, you aren't really hearing Dylan anymore. You're hearing the ghost of 1968. You're hearing a sonic explosion that Dylan himself eventually started imitating because he realized Jimi did it better.

It’s a strange phenomenon.

Dylan wrote it as a sparse, eerie folk tune for John Wesley Harding. It was quiet. It was apocalyptic in a "hushed tones around a campfire" kind of way. Then Hendrix got his hands on it at Olympic Studios in London, and suddenly the song had teeth. It had a snarl.

But the studio version is only half the story. To understand why this track still dominates classic rock radio and Spotify playlists, you have to look at the way it evolved on stage. From Jimi's pyrotechnic displays to Dave Matthews Band’s sprawling jams and Dylan’s own grit, the live evolution of this song is a masterclass in musical mutation.

The Hendrix Blueprint and the 1970 Revolution

If you want to talk about the definitive version, you have to start with Jimi at the Isle of Wight in 1970. It was just weeks before he died. He was exhausted. He was struggling with sound issues. Yet, when he launched into those opening chords, the atmosphere changed.

The live versions Hendrix played weren't just carbon copies of the record. He treated the solo sections like a conversation. On the original recording, there are four distinct solo sections: the slide part (played with a Zippo lighter, supposedly), the wah-wah section, the rhythmic chord solo, and the final melodic burn. Live? He’d stretch those out until they bled into the next song.

He made the guitar talk.

Most people don't realize that Jimi was actually nervous about his voice. He thought he couldn't sing Dylan’s lyrics justice. But live, his phrasing was impeccable. He spat out the lines about jokers and thieves like he was reporting from a war zone. When he played it at the Atlanta International Pop Festival in July 1970, the sheer volume was enough to shake the foundations of the stage. It wasn't just a song; it was a physical event.

Why Dylan Started Covering His Own Cover

Here is the funniest part of music history: Bob Dylan basically retired his own version of the song.

After Hendrix died, Dylan started performing the song live during his 1974 tour with The Band. But he didn't play the folk version. He played it like Jimi. He cranked the volume. He let the lead guitarists take center stage.

"I liked Jimi Hendrix’s record of this and ever since he died I’ve been doing it that way," Dylan once remarked. It’s a rare moment of humility from a man who is usually a bit of a cryptic enigma. He acknowledged that Hendrix found something in the lyrics—a sense of urgency—that Dylan hadn't quite captured in the studio.

If you listen to Dylan’s Before the Flood live album, the energy is frantic. It’s fast. It’s almost punk rock before punk existed. He’s been playing all along the watchtower live for decades now, and it has appeared in his setlists more than almost any other song—over 2,200 times. That is an insane amount of times to play one song.

He changes the arrangement constantly. Sometimes it’s a blues shuffle. Sometimes it’s a wall of distorted noise. In the late 90s, he’d often use it as a set closer, letting his touring guitarists like Charlie Sexton or Larry Campbell engage in dual-guitar warfare. It’s like Dylan is trying to reclaim the song from Jimi’s ghost, but he knows he’s fighting a losing battle.

The Dave Matthews Band and the Modern Jam

If you grew up in the 90s or 2000s, your version of this song might actually be the one played by Dave Matthews Band (DMB).

They turned it into a marathon.

While Hendrix kept it around four or five minutes, DMB would regularly push it to twelve or fifteen. They’d bring in guest musicians—everyone from Béla Fleck on banjo to Trey Anastasio from Phish. The DMB version is built on Stefan Lessard’s driving bass line and Carter Beauford’s relentless drumming.

It’s polarizing. Purists hate it. Fans live for it.

The "Central Park Concert" version from 2003 is often cited as a high-water mark for the band. It features a massive violin solo from Boyd Tinsley and an interpolation of "Stairway to Heaven." Is it overindulgent? Probably. But that’s the point of a live performance. It’s supposed to be a spectacle. They took the "watchtower" and turned it into a stadium anthem.

U2, Neil Young, and the Heavy Hitters

The song has become a sort of litmus test for rock royalty. If you’re a big-name guitarist, you eventually have to tackle the Watchtower.

U2 threw it into their Rattle and Hum era performances. Bono would often spray-paint "Rock and Roll" on the stage scenery while The Edge tried to mimic Hendrix's feedback. It was gritty and industrial.

Then you have Neil Young. When Neil plays it, especially with Booker T. & the M.G.'s or Crazy Horse, it becomes a distorted mess in the best way possible. Neil doesn't care about the "correct" notes. He cares about the feeling. His solos are jagged. They sound like a building collapsing.

- The Grateful Dead: They played it about 120 times, usually in the second set. Jerry Garcia’s tone was cleaner than Jimi’s, giving it a trippy, celestial vibe.

- Bear McCreary: For the Battlestar Galactica fans, the live orchestral versions of this song are haunting. It uses sitars and heavy percussion to make it sound ancient.

- Prince: His Super Bowl XLI halftime show featured a medley that included a nod to the song. Even in the rain, the purple one made it look easy.

The Technical Difficulty of Getting it Right

Why is it so hard to play live?

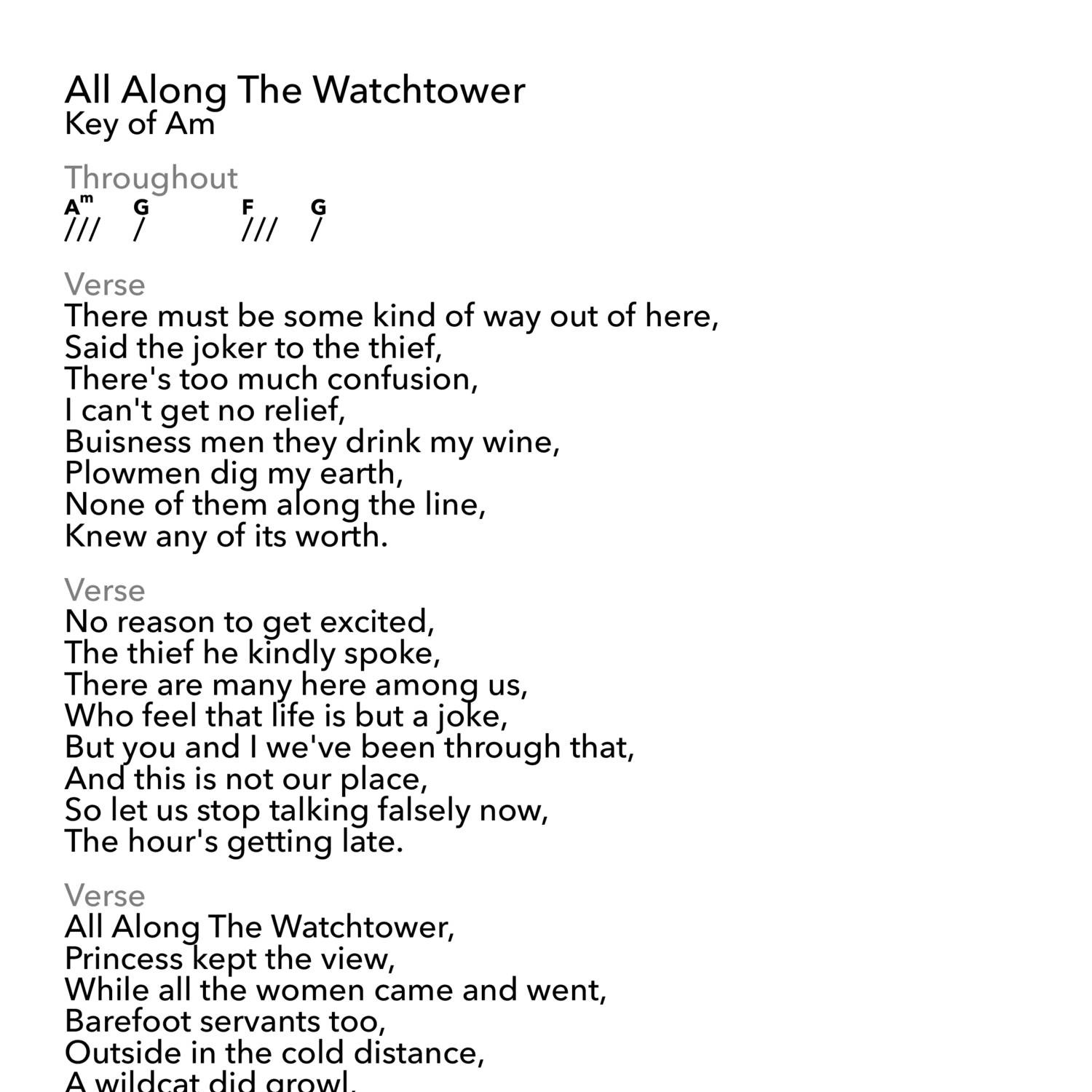

On paper, it’s just three chords: C#m, B, and A (if you're playing in the Hendrix key). That’s it. It’s a descending loop.

The difficulty isn't the chords; it's the pocket. If the drummer plays it too straight, it sounds like a boring bar band cover. If the guitarist doesn't understand how to use a wah-wah pedal or how to manipulate feedback, it feels empty.

You also have the lyrical structure. The song is written in reverse. The "story" starts at the end and ends at the beginning. "Two riders were approaching, the wind began to howl." That’s the start of a story, but it’s the final line of the song. Live performers have to maintain that tension for the entire duration without it becoming repetitive.

👉 See also: Sutton Foster Anything Goes: Why This Performance Still Matters

What to Look for in a Great Live Recording

If you’re diving into the archives of all along the watchtower live, don't just stick to the hits. Look for the "audience tapes" or the soundboard boots.

- Check the Tempo: The studio version is mid-tempo. The best live versions are usually slightly faster, pushing the energy until it feels like it might go off the rails.

- The Intro: The opening riff is iconic. Listen to how the performer handles the "stab" chords. Do they ring out, or are they muted?

- The Transitions: Some bands use the song to transition into other tracks. The Dead would often weave it in and out of "drums" and "space."

- The Vocal Delivery: Dylan’s growl vs. Jimi’s soul vs. Dave Matthews’ scatting. Each changes the meaning of the lyrics.

The Legacy of the Live Watchtower

There is no "final" version of this song. That’s the beauty of it. It’s a living document.

Every time a teenager picks up a Stratocaster and tries to figure out that opening solo, the song is reborn. Every time a legacy act plays it at a summer shed tour, it gains a new layer of history.

It has survived the transition from acoustic folk to psychedelic rock to 80s stadium rock to the jam band scene. It’s a piece of music that refuses to be dated. It’s timeless because it’s about something primal—fear, escape, and the feeling that something big is about to happen.

How to Experience the Best Versions Today

If you want to actually hear the evolution, skip the greatest hits albums for a second. Go to YouTube or a high-res streaming service and look for these specific captures:

- Hendrix at the Isle of Wight (1970): It’s messy, loud, and beautiful. It captures the chaos of the era perfectly.

- The Jimi Hendrix Experience at Winterland (1968): This is Jimi at his technical peak.

- Bob Dylan at Woodstock '94: It shows his "electric" elder statesman phase. He sounds like he’s having the time of his life.

- Dave Matthews Band - Live at Red Rocks 8.15.95: This is the band when they were hungry and trying to prove themselves.

The best way to appreciate the song is to listen to three different live versions back-to-back. You’ll start to see the patterns. You'll hear the way guitarists quote each other. You'll realize that the "watchtower" isn't a place—it's a sound.

Next time you're at a concert and you hear those three chords start to churn, pay attention to the crowd. Even people who don't know the lyrics know the feeling. It’s the sound of the wind beginning to howl.

Go find a high-quality bootleg of a 1970s show or a modern 4K concert film. Crank the volume. Pay attention to the bridge—that's where the real magic usually happens when the band stops thinking and just starts playing. Look for the nuance in the feedback. That's where the soul of the song lives now.