It starts with that four-chord progression. It’s a chromatic descent, circling from E minor down to G, D, and C, but it doesn't feel like a standard rock song. It feels like a long sigh. Or maybe a funeral march for someone who is still technically breathing. When Layne Staley’s voice finally enters the frame of Alice in Chains Nutshell, he sounds tired. Not just "end of a long tour" tired, but soul-exhausted.

Most people know the version from the MTV Unplugged session in 1996. You know the one. The stage is littered with black candles. Layne is wearing pink sunglasses to hide his eyes, and his hair is a shock of pastel pink. He looks frail. When he sings that opening line—"We chase misprinted lies"—there is a collective hush that hasn't really left the room in thirty years. It’s arguably the most honest three minutes in the history of the Seattle grunge movement. It’s also a masterclass in how to say everything while barely raising your voice.

The Jar of Flies sessions and the birth of a masterpiece

To understand how we got here, you have to look at 1993. The band had just come off a massive tour for Dirt. They were burned out. They were also homeless, essentially, having been evicted from their residence while on the road. They moved into London Bridge Studio in Seattle with nothing written. Seriously, nothing. Producer Toby Wright has mentioned in interviews that the band just started jamming to see what would stick.

Alice in Chains Nutshell wasn't some overproduced radio hit. It was a mood that turned into a song. Jerry Cantrell, the primary architect of the band's sound, brought in those acoustic layers that defined the Jar of Flies EP. People usually associate Alice in Chains with the sludgy, metallic riffs of "Man in the Box," but this was different. It was stripped back. It was vulnerable. It was also incredibly fast; the entire EP was recorded and mixed in just seven days. That kind of pressure usually breaks a band, but for them, it acted as a vacuum that sucked out all the pretense.

The song is short. It doesn't have a bridge. It doesn't have a soaring, triumphant chorus. It just cycles. It’s a loop of despair that mirrors the cycle of addiction and public scrutiny the band was facing at the time.

Why the Unplugged performance is the definitive version

If the studio version is a painting, the Unplugged version is a photograph. It’s reality. By 1996, Alice in Chains hadn't performed live in two and a half years. The rumors were everywhere. People thought Layne was dead or dying. When they stepped onto that stage at the Majestic Theatre, the tension was thick enough to choke on.

Jerry Cantrell has talked about how nervous they were. He was actually dealing with a nasty case of food poisoning during the taping. He had a bucket off-stage just in case. But when they started Alice in Chains Nutshell, the illness and the nerves seemed to vanish into the atmosphere.

Layne’s delivery is hauntingly precise. He misses a lyric later in the set on "Sludge Factory," but on "Nutshell," he is perfect. The way he emphasizes the word "hollow" feels literal. It’s not just a singer performing a sad song; it’s a man documenting his own disappearance. Mike Inez wrote "Friends Don't Let Friends Get Friends Haircuts" on his bass as a dig at the Metallica members in the audience, which adds a weird, darkly humorous layer to such a heavy night, but the music itself remained untouchable.

The lyrics: Loneliness as a physical space

"No one to cry to / No place to call home."

It’s simple. It’s almost childlike in its directness. But that’s the secret sauce of Alice in Chains Nutshell. It avoids the flowery metaphors that a lot of 90s songwriters used to sound deep. It just tells you the truth: being a rock star doesn't stop you from feeling like a ghost.

The song tackles the loss of privacy. By the mid-90s, the Seattle scene was under a microscope. Every time Layne stumbled, it was a headline. The "misprinted lies" he sings about weren't just about the media, though. They were about the internal lies an addict tells themselves to keep going. The song is a declaration of independence, but a lonely one. "I can feel as I wish only to be all alone." It’s a boundary being drawn in the sand.

The technical soul of the song

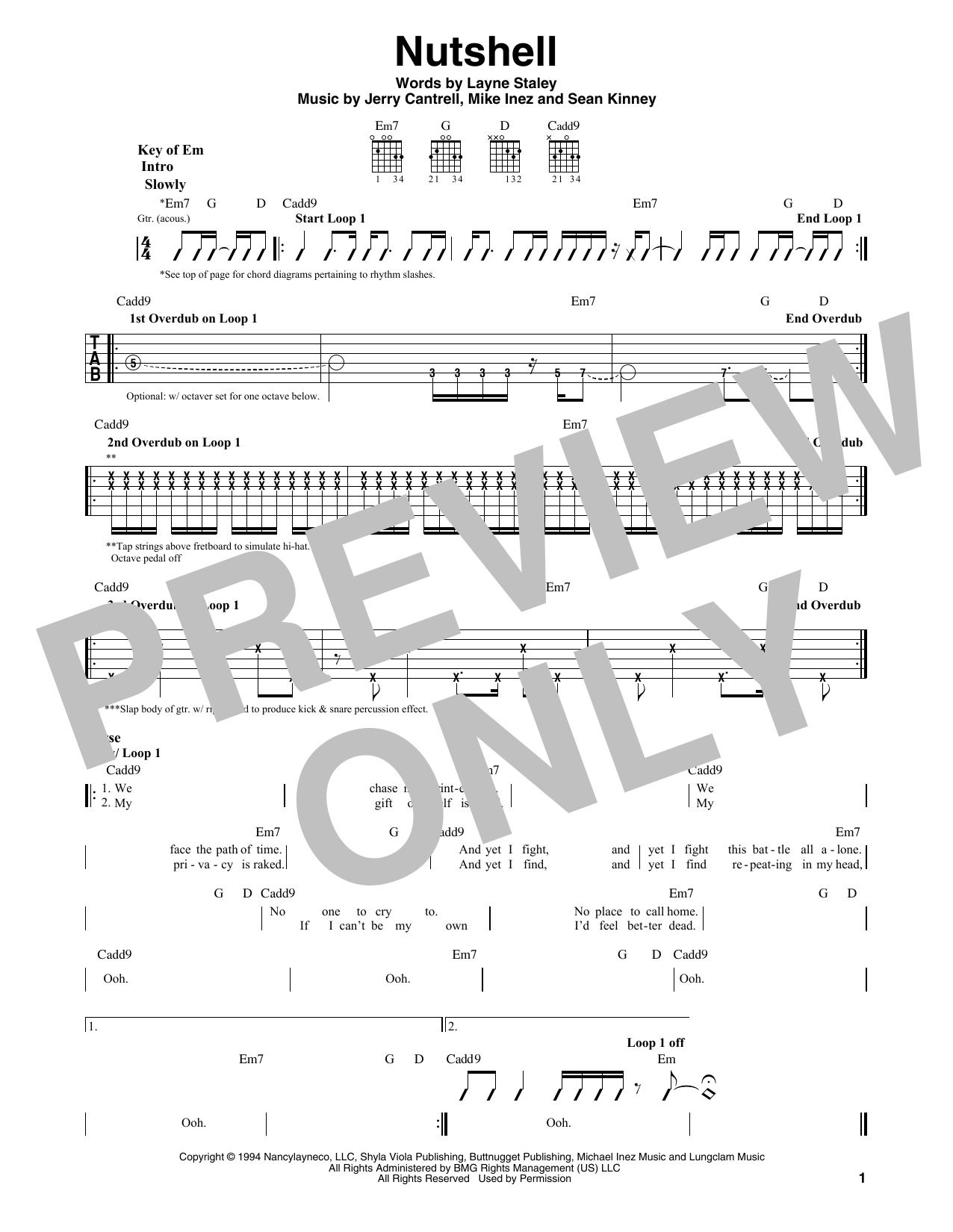

Musically, the song is a bit of a trick. It uses an Em7 - G - D - Cadd9 progression. In any other context, those are "happy" chords used in folk music or campfire songs. But Jerry Cantrell plays them with a specific weight. He uses a lot of open strings, letting the notes ring out and bleed into each other.

💡 You might also like: This Is Our God: Why the 2008 Hillsong Album Still Hits Different

And then there’s the solo.

It’s not a shredder solo. It’s a melody that follows the vocal line. Cantrell’s guitar work on Alice in Chains Nutshell is often cited by guitarists as one of the most emotional pieces of playing ever recorded. He uses a wah-pedal not to make "funky" noises, but to make the guitar sound like it’s weeping. It’s subtle. It’s tasteful. It’s devastating.

The bass line by Mike Inez is also a sleeper hit here. He doesn't just follow the root notes. He plays these little melodic fills that bridge the gap between the acoustic guitar and Layne’s voice. It gives the song a foundation that feels like it’s shifting under your feet. Sean Kinney’s drumming is equally restrained. He isn't hitting hard; he’s just keeping time for a world that’s slowing down.

A legacy that refuses to fade

You see it on TikTok. You see it on YouTube. Teenagers who weren't even born when Layne Staley died in 2002 are discovering Alice in Chains Nutshell and having the same visceral reaction people had in 1994. Why? Because loneliness hasn't gone out of style. If anything, the isolation of the digital age has made the song more relevant.

It has been covered by everyone. Shinedown, Staind, Ryan Adams, even country artists. But nobody quite captures the original’s specific blend of resignation and beauty. It’s a "lightning in a bottle" track. You can’t recreate the specific pain that was in that room in 1993 or the specific fragility of that stage in 1996.

There’s a common misconception that the song is "pro-drug" or "glorifying misery." Honestly, it’s the opposite. It’s a warning. It’s a vivid depiction of where that road leads. It leads to a nutshell. A small, cramped, lonely space where you are "all alone."

How to truly appreciate the track today

If you want to hear it the right way, don't play it on your phone speakers while you're doing the dishes. That's a waste.

- Find the Unplugged vinyl or a high-res stream. You need to hear the space between the notes. The room tone of the Majestic Theatre is part of the instrument.

- Watch the video. Specifically, watch Layne’s hands. He’s fidgeting. He’s present but also miles away. Seeing the band's chemistry—the way they look at him with a mix of love and concern—changes how you hear the harmonies.

- Listen to the bass. Most people focus on the vocals, but Mike Inez’s tone on this track is one of the best acoustic bass sounds ever captured.

Moving forward with the music

The best way to honor the legacy of Alice in Chains Nutshell is to recognize its humanity. It’s a reminder that it is okay to not be okay, but it’s also a call to look at the people around you who might be "chasing misprinted lies" of their own.

If you're a musician, study the phrasing. If you're a fan, just let it wash over you. The song doesn't ask for much. It just asks you to listen. It remains a cornerstone of the "Seattle Sound" not because it was loud, but because it was the quietest moment in a very loud decade.

👉 See also: No Exit Jean-Paul Sartre PDF: Why You Should Stop Searching and Start Reading

For those looking to dive deeper into the history of the band, reading Alice in Chains: The Untold Story by David de Sola offers a grounded, factual look at the sessions that birthed this track without the sensationalism often found in grunge retrospectives. Also, check out the isolated vocal tracks available online; hearing Layne and Jerry’s harmonies without the instruments reveals the intricate, haunting work that went into their "vocal telepathy."

The song ends with a final, fading guitar note. It doesn't resolve. It just stops. And that is exactly how it should be.