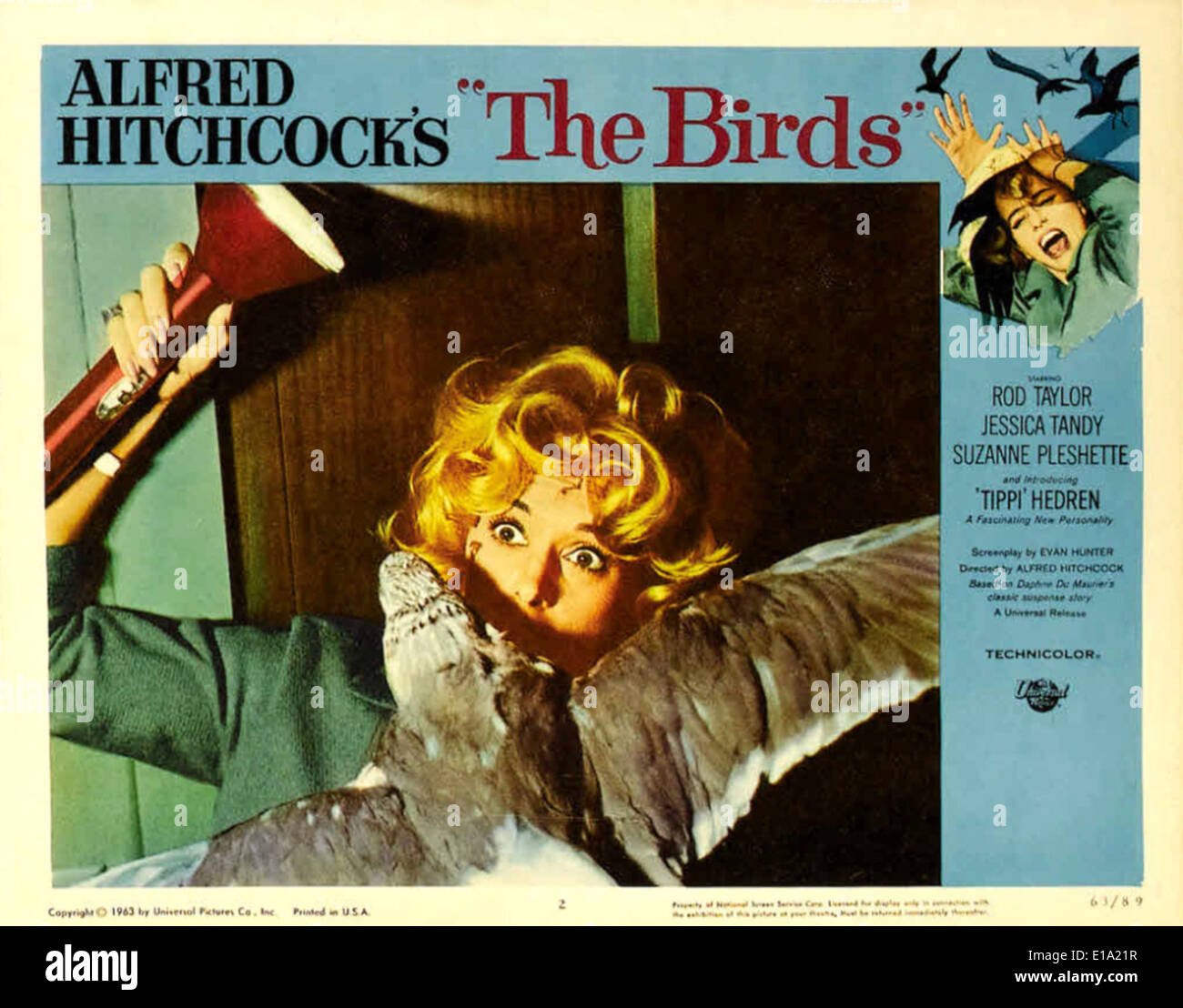

Ever looked at a crow sitting on a telephone wire and felt a tiny shiver? That’s his fault. Alfred Hitchcock. Specifically, the Alfred Hitchcock movie The Birds. It’s 1963. Audiences walk into a theater expecting a thriller, but they leave afraid of the sky.

The movie is weird. Honestly, it’s one of the strangest films in the Master of Suspense’s entire filmography because it refuses to explain itself. There is no radioactive spill. No ancient curse. No mad scientist. Just birds. Lots of them. And they are very, very angry.

The Bodega Bay Nightmare

Bodega Bay is a real place. It’s quiet. Or it was, until Hitchcock showed up with a truckload of trained ravens and a very stressed-out Tippi Hedren. The plot starts out like a lighthearted romantic comedy, which is a classic Hitch move. Melanie Daniels, a wealthy socialite, chases a lawyer named Mitch Brenner to his weekend home. She brings lovebirds. It’s cute.

Then a seagull hits her in the head.

From there, the tension doesn't just ramp up; it suffocates. You’ve got these massive set pieces, like the explosion at the gas station or the playground scene where the crows slowly gather on the climbing frame behind Melanie. It’s a masterclass in pacing. He doesn't show the attack immediately. He shows the anticipation of the attack. That’s why the Alfred Hitchcock movie The Birds works so well even in 2026. Jump scares are cheap. Waiting for a bird to blink? That’s true horror.

🔗 Read more: Anjelica Huston in The Addams Family: What You Didn't Know About Morticia

Why the Special Effects Were Revolutionary (and Dangerous)

People forget how hard this movie was to make. This was way before CGI. If you see a hundred birds on screen, a lot of them were real. Ub Iwerks, the guy who helped create Mickey Mouse, worked on the special effects. They used something called the "yellow screen" process. It was basically a precursor to blue screen technology but used sodium vapor lamps. It allowed Hitchcock to layer footage of real birds over the actors with incredible precision for the time.

But the reality on set was brutal.

Tippi Hedren literally went through hell. For the final attic scene, where Melanie is shredded by wings and beaks, Hitchcock told her they’d use mechanical birds. He lied. For five days, assistants threw live gulls, ravens, and crows at her. They were tied to her clothes with nylon threads. One almost took out her eye. She had a nervous breakdown. Production shut down for a week. When you see the terror on her face in that scene, you aren't watching acting. You're watching a person who is genuinely traumatized.

The Sound of Silence

Notice something missing? Music. There is no traditional orchestral score in the Alfred Hitchcock movie The Birds. None. No violins. No booming drums. Instead, Hitchcock used a Mixtur-Trautonium, an early electronic instrument, to create stylized bird sounds.

💡 You might also like: Isaiah Washington Movies and Shows: Why the Star Still Matters

Bernhard Herrmann, Hitchcock’s usual composer, acted as a "sound consultant." They wanted the birds to sound like a machine. Screeching. Flapping. Whirring. By stripping away the music, Hitchcock forced the audience to live in the raw, uncomfortable silence of the California coast. It makes the attacks feel more visceral. More "real." You can't hide behind a cinematic melody.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Ending

People hate the ending. Or they love it because they hate it. There is no "The End" title card. The car just crawls away into a landscape filled with thousands of waiting birds. The mystery is never solved. Why did they attack?

Some scholars, like Camille Paglia, argue the birds are a manifestation of female repressed rage or the chaotic nature of the "Mother" figure, represented by Mitch’s clingy mom, Lydia. Others think it’s just a nihilistic take on nature reclaiming the earth. Hitchcock himself liked the ambiguity. He wanted you to drive home looking out your sunroof, wondering if the crows in your neighborhood had reached their breaking point yet.

The Real-Life Inspiration: It Actually Happened

Think the story is totally made up? Nope. While the movie is based on a Daphne du Maurier short story, a real event in 1961 heavily influenced Hitchcock. In Capitola, California, thousands of Sooty Shearwaters started slamming into houses and cars. They were vomiting half-digested fish and dying in the streets.

📖 Related: Temuera Morrison as Boba Fett: Why Fans Are Still Divided Over the Daimyo of Tatooine

It turned out to be toxic algae—domoic acid poisoning—that disoriented the birds. But at the time, it looked like an uprising. Hitchcock called the local newspaper to ask for clippings about the event. He used the real-world terror of "nature gone wrong" to ground his supernatural premise in a terrifying reality.

Lessons for Modern Filmmakers and Fans

The Alfred Hitchcock movie The Birds teaches us that the most effective horror is often the most familiar. We see birds every day. They are part of the background noise of life. By turning the mundane into the murderous, Hitchcock ruined parks and beaches for an entire generation.

If you’re looking to truly appreciate this film, don't watch it on a tiny phone screen. Turn off the lights. Crank the volume. Listen to those mechanical bird shrieks.

How to Experience The Birds Today

- Watch the 4K Restoration: The colors in the 1960s Technicolor are vivid, making the red blood and the blue California sky pop in a way that feels hyper-real.

- Read the Original Story: Daphne du Maurier’s novella is much darker and set in post-war Britain. It provides a fascinating contrast to Hitchcock’s glamorous American version.

- Visit Bodega Bay: You can still see the schoolhouse and the church from the film. Just... maybe don't bring any birdseed.

- Listen to the Sound Design: Pay attention to the moments of total silence. It’s a technique modern directors like Robert Eggers or Ari Aster use to build dread.

Nature isn't always our friend. Sometimes, it's just waiting for us to look away. Hitchcock knew that. And now, every time you see a crow staring at you from a fence post, you know it too.