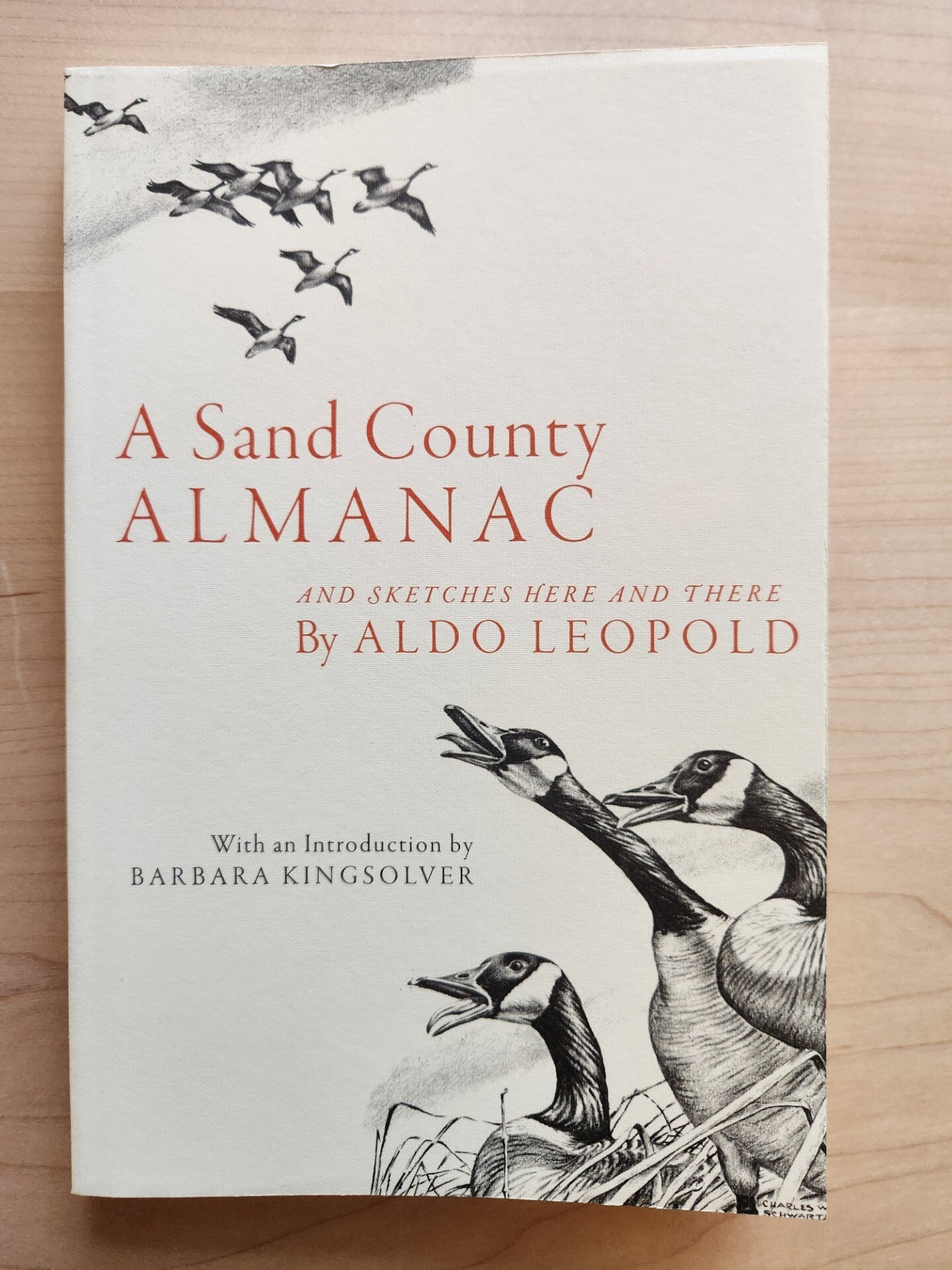

If you pick up a copy of Aldo Leopold’s A Sand County Almanac, you might expect a dry textbook on forestry or a dense manual on soil nitrates. Instead, you get a ghost story. It’s the story of a man watching the world fade away in real-time and trying to figure out if we can save it without losing our souls in the process.

Leopold wasn’t some hippie shouting from a soapbox. He was a hunter. He was a professor at the University of Wisconsin. He was a guy who bought a "worthless" piece of land in Sauk County, Wisconsin—literally a sand farm that had been worked to death—and moved his family into a renovated chicken coop to see if they could bring the dirt back to life.

Honestly, the book is a slow burn. It starts with "January Thaw," where Leopold tracks a skunk through the snow. It sounds simple, right? But he’s actually teaching you how to see. Most of us walk through the woods and see "trees." Leopold walks through the woods and sees a 200-year-old oak tree that just fell, and as he saws through the rings, he recounts the history of the state: the year the last passenger pigeon was seen, the year of the great drought, the year the settlers arrived. He turns a cross-cut saw into a time machine.

The Land Ethic: It’s Not What You Think

People toss around the term Land Ethic like it’s a slogan on a tote bag. But for Leopold, it was a radical shift in how humans view themselves. Basically, we’ve always seen ourselves as the conquerors of the land. We own it. We use it. We dump stuff on it.

Leopold argued that we need to stop being conquerors and start being "plain members and citizens" of the biotic community.

Think about that for a second. It means the soil, the water, the plants, and the animals have a right to exist, regardless of whether they make us money. He famously wrote that a thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise.

It’s a simple rule. Hard to follow, though.

In 2026, we’re still struggling with this. We talk about carbon credits and ESG scores, but those are just ways of accounting. Leopold wasn't interested in accounting. He wanted a change of heart. He knew that you can’t protect what you don't love, and you can't love what you don't understand.

Thinking Like a Mountain

There’s a chapter in A Sand County Almanac called "Thinking Like a Mountain" that every student of ecology eventually has to reckon with. It’s arguably the most famous part of the book.

Leopold describes a moment from his youth when he was working for the U.S. Forest Service. Back then, the policy was simple: wolves are bad because they kill deer. If you kill all the wolves, you get more deer, and that makes the hunters happy.

✨ Don't miss: Why T. Pepin’s Hospitality Centre Still Dominates the Tampa Event Scene

So, he and his buddies saw a wolf crossing a river and opened fire. They reached the wolf just in time to watch a "fierce green fire" dying in her eyes.

He realized something that day.

When the wolves are gone, the deer population explodes. The deer eat every green shoot on the mountain until there’s nothing left. Then the deer starve. The mountain, which feared the wolf, now fears the deer even more because the deer destroy the very foundation of the ecosystem.

It’s a lesson in unintended consequences. We think we can "fix" nature by removing the parts we don't like, but nature is a web, not a machine. You pull one thread, and the whole thing starts to unravel.

The Problem with "Good" Conservation

Leopold was surprisingly cynical about "official" conservation. He saw the government spending millions on projects that didn't work because they were focused on the wrong things.

- He hated that we only value nature when it’s "useful."

- He worried that outdoor recreation was becoming a "gadget-heavy" industry rather than a spiritual experience.

- He saw the loss of "wilderness" as a permanent scar on the human psyche.

He wasn't against progress. He was against progress that lacked a conscience.

The Shack and the Sand Farm

The "Almanac" part of the book follows the months of the year at his weekend retreat, "The Shack." This wasn't some luxury cabin with Wi-Fi. It was a place where he planted thousands of pine trees by hand.

He watched the woodcock do its "sky dance" in April.

He listened to the "choral" of the birds at 4:00 AM in July.

He tracked the movements of a single chickadee, #65243, to see how it survived the winter.

This level of detail is what makes A Sand County Almanac feel human. It’s not a manifesto written from an ivory tower; it’s a field journal from a guy who got his boots muddy. He proves that restoration is possible. That dead sand farm in Wisconsin eventually became a thriving forest again. It took decades of work, but it happened.

🔗 Read more: Human DNA Found in Hot Dogs: What Really Happened and Why You Shouldn’t Panic

Why 2026 Needs Leopold More Than Ever

We live in a world of screens and "smart" everything. Most people can recognize a hundred corporate logos but can't identify three species of native trees in their own backyard.

Leopold warned us about this. He called it the "spiritual danger" of not owning a farm. He said there are two dangers in not owning a farm: one is the belief that breakfast comes from the grocery store, and the other is that heat comes from the furnace.

If you don't know where your food or your warmth comes from, you stop caring about the health of the earth that provides them. You become a passenger instead of a crew member.

A Sand County Almanac asks us to look at the world differently. It’s not just "resources." It’s a community.

Misconceptions About Leopold

People often mistake Leopold for a preservationist—someone who wants to lock up nature and keep people out. He wasn't that. He was a conservationist who believed in the "wise use" of land. He hunted. He fished. He cut down trees.

The difference was how he did it.

He believed that if you take from the land, you have a moral obligation to give back. You can't just be a taker.

Actionable Insights: How to Apply the Land Ethic Today

You don't need to buy a 40-acre sand farm to follow Leopold’s lead. You can start where you are.

1. Learn the names of your neighbors.

Not just the people in the house next door. Find out what kind of birds live in your trees. Identify the weeds growing in the cracks of the sidewalk. Once you know their names, you start to notice when they’re gone.

💡 You might also like: The Gospel of Matthew: What Most People Get Wrong About the First Book of the New Testament

2. Practice "perceptive" recreation.

The next time you go for a hike, leave the headphones at home. Don't worry about your "pace" or your "steps." Look for tracks. Listen for the wind in different types of trees—Leopold noted that pines "sigh" while oaks "rattle."

3. Reduce your "trophy" mentality.

Whether it’s hunting, fishing, or even just taking photos for Instagram, stop trying to "conquer" the outdoors. Try to be a part of it instead.

4. Support local restoration.

Look for groups in your area that are planting native species or cleaning up watersheds. Leopold showed us that even the most damaged land can be healed if someone cares enough to try.

5. Read the book. Seriously. It’s short. You can read it in a weekend. But the ideas in it will probably stick with you for the rest of your life.

Aldo Leopold died in 1948 while helping a neighbor fight a grass fire. He never saw A Sand County Almanac published; it came out a year later. He didn't live to see the modern environmental movement he helped inspire. But his voice is louder now than it was then.

The "fierce green fire" is still out there. We just have to be quiet enough to see it.

Next Steps for the Inspired Reader

To truly understand the impact of Leopold's work, visit the Aldo Leopold Foundation website to see photos of the original Shack and learn about ongoing restoration projects. Alternatively, pick up a field guide to the birds or trees in your specific region and commit to identifying one new species every week for a month. Observation is the first step toward ethics.