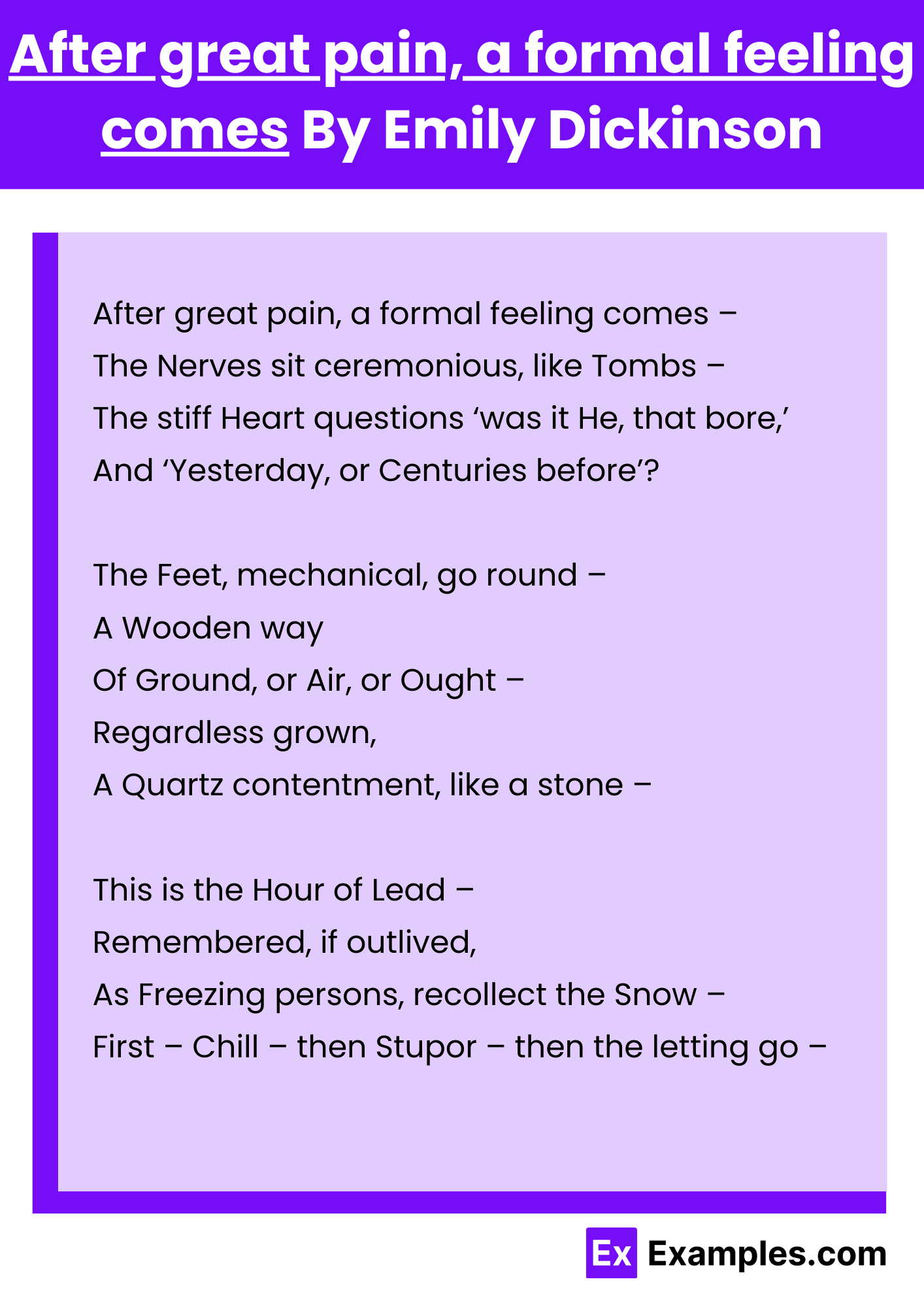

Pain is loud. Until it isn't. Most of us expect the "great pain" of loss to be a screaming, chaotic mess of tears and broken glass, but Emily Dickinson knew better. She wrote After great pain a formal feeling comes around 1862, right in the middle of the American Civil War, a time when death was everywhere. But she wasn't writing about the battlefield. She was writing about the weird, icy stillness that happens when your brain basically shuts down to protect itself.

It’s that "formal" part that trips people up. You’d think grief would be messy. Instead, Dickinson describes it as stiff. Stately. Like a funeral procession happening inside your own nerves.

Have you ever noticed how, after a massive shock, you suddenly find yourself doing the dishes with military precision? Or you're standing in line at the grocery store and you feel like a ghost inhabiting a mannequin? That’s the "formal feeling." It’s a psychological survival mechanism. Dickinson was a master of capturing these internal "landscapes" that most people are too scared to look at. Honestly, her ability to map out the anatomy of a breakdown is almost clinical, despite being written in 19th-century verse.

The Stiff Heart and the Wooden Way

The poem starts with that iconic line, After great pain a formal feeling comes, and then it moves straight into the physical sensation of being numb. She mentions "The Nerves sit ceremonious, like Tombs." Think about that for a second. Your nerves—the things that are supposed to make you feel—are sitting still like gravestones.

It’s heavy.

Dickinson uses these bizarre, jarring metaphors to show how grief turns a person into an object. The "Stiff Heart" wonders if it was really it that bore the pain, and if it was even that long ago. Time becomes a blur. Yesterday feels like a century ago; an hour ago feels like it never happened. When you're in the thick of it, the "formal feeling" acts as a kind of emotional anesthesia. You move through the world "mechanically," a word she specifically chooses to describe the way we walk when we’re grieving—a "Wooden way" of "Regardless grown."

Basically, you’re on autopilot. You’re walking on air, but not in a good way. It’s more like walking on a floor that isn't there, or "Ground, or Air, or Ought." You just don't care where your feet land.

This is the Hour of Lead

One of the most famous parts of the poem is the "Hour of Lead." If you’ve ever felt like your limbs weighed a thousand pounds after a breakup or a death, you know exactly what she’s talking about. It’s a specific kind of exhaustion. It isn't just being tired; it’s a heavy, metallic pressure.

Psychologically, this aligns with what modern therapists call "depersonalization" or "dissociation." When the "great pain" is too much for the psyche to process at once, the mind creates a buffer. This isn't a sign of weakness. It’s actually the brain’s way of keeping you from literal system failure. Dickinson describes the progression of this feeling: "First—Chill—then Stupor—then the letting go."

It’s a chilling trajectory.

- The Chill: The initial shock where the world turns cold.

- The Stupor: The "formal feeling" takes over and you become a zombie.

- The Letting Go: This is the most debated part. Does it mean death? Or does it mean the numbness finally breaks and the "real" grieving—the messy, crying part—finally starts?

Most scholars, like Cynthia Griffin Wolff, suggest that the "letting go" is the final surrender to the numbness. It’s the moment the survivor stops fighting the cold and just... sinks. It’s like freezing to death in the snow. If you fight the cold, you're still alive. Once you stop feeling the cold and start feeling warm and sleepy, that's when you're in real trouble.

Why Dickinson’s "Formal Feeling" Matters in 2026

You might wonder why a poem from 160 years ago is still trending on TikTok or being cited in grief support groups. It's because we still don't have better words for it. In a world that's constantly telling us to "heal out loud" or "process your trauma," Dickinson gives us permission to just be numb.

Sometimes, you can't process. Sometimes, the "great pain" is so massive that the only way to survive the next ten minutes is to become "formal."

There’s a huge misconception that if you aren't crying, you aren't grieving. That’s nonsense. Dickinson’s poem is a defense of the quiet mourner. It’s for the person who looks "fine" at the funeral but feels like their soul is made of lead and quartz. She mentions "Quartz contentment," which is a brilliant, terrifying phrase. Quartz is hard, cold, and translucent. It’s a "contentment" that comes from being incapable of feeling anything else. It's not happiness; it's just the absence of the ability to hurt anymore.

Misconceptions About the Poem

A lot of people read After great pain a formal feeling comes and think it’s a poem about recovery. It really isn't. It’s a poem about the middle of the storm, the eye of the hurricane where everything is deceptively still.

Another common mistake is thinking the "Pain" she refers to has to be a death. While Dickinson dealt with plenty of loss (her father, her friends, her favorite dog), the poem is vague enough to apply to any catastrophic internal shift. It could be the end of a career, a spiritual crisis, or even a localized depression. The "great pain" is the catalyst; the "formal feeling" is the result.

Actionable Insights for Navigating the "Formal Feeling"

If you find yourself in the "Hour of Lead," it’s easy to feel like you’re losing your mind because you feel nothing. Here is how to handle that phase without spiraling:

Acknowledge the Numbness as Protection

Stop trying to force yourself to feel "the right way." If you are in the "formal" stage, your brain is doing you a favor. It’s a circuit breaker. Let it be. Trying to force a "breakthrough" when you're in the "Stupor" phase can actually lead to more severe dissociation.

The "Wooden Way" Strategy

When you’re moving mechanically, lean into routine. Dickinson’s "mechanical" feet kept moving. If all you can do is the laundry and walking the dog without feeling a spark of joy or sadness, do those things. The routine provides the "formal" structure that keeps you from collapsing entirely.

📖 Related: Finding Restaurants for Thanksgiving Without Losing Your Mind (Or Your Deposit)

Identify the "Chill"

Watch for the physical signs. Dickinson was hyper-aware of the body. Cold hands, a heavy chest, a feeling of being "out of body"—these are physiological markers of the "Hour of Lead." Recognizing them as symptoms of a "formal feeling" rather than a permanent change in your personality can help reduce the anxiety of the experience.

Wait for the "Letting Go" Carefully

The transition out of numbness is often more painful than the numbness itself. As the "formal feeling" fades, the "great pain" usually returns in a more manageable, but still intense, form. Ensure you have a support system—a friend, a therapist, or even a creative outlet—for when the "Quartz contentment" starts to crack.

The "formal feeling" isn't a destination. It’s a transit lounge. You aren't meant to live there forever, but you also can’t rush the departure. Dickinson’s poem serves as a map for a place no one wants to visit, but everyone eventually does. By naming the "stiff Heart" and the "Hour of Lead," she makes the isolation of grief feel a little less lonely. You’re not a robot; you’re just "ceremonious." And eventually, the lead will lighten, even if it feels like it never will.