Tennessee Williams didn't just write a play; he built a pressure cooker and invited us to watch it explode. Most people encounter A Streetcar Named Desire in a high school English class or through a grainy clip of Marlon Brando screaming "Stella!" in a soaked undershirt. But if that’s all you know, you’re missing the actual point. It’s a messy, sweaty, loud piece of theater that basically redefined what American drama could be.

It's 1947. The war is over. New Orleans is humming with this weird, electric energy of the New South, and then Blanche DuBois shows up on her sister’s doorstep with a trunk full of fake rhinestones and a lot of secrets. It’s uncomfortable. Honestly, it's supposed to be.

The Reality of Blanche DuBois vs. Stanley Kowalski

The heart of A Streetcar Named Desire is a collision between two people who literally cannot exist in the same room. On one side, you have Blanche. She’s the remnant of the "Old South"—all manners, lace, and delicate sensibilities that are actually just a mask for trauma and a drinking problem. On the other, you have Stanley. He’s the new world. He’s raw, blue-collar, and doesn't give a damn about "refined" conversation.

People often make the mistake of picking a side.

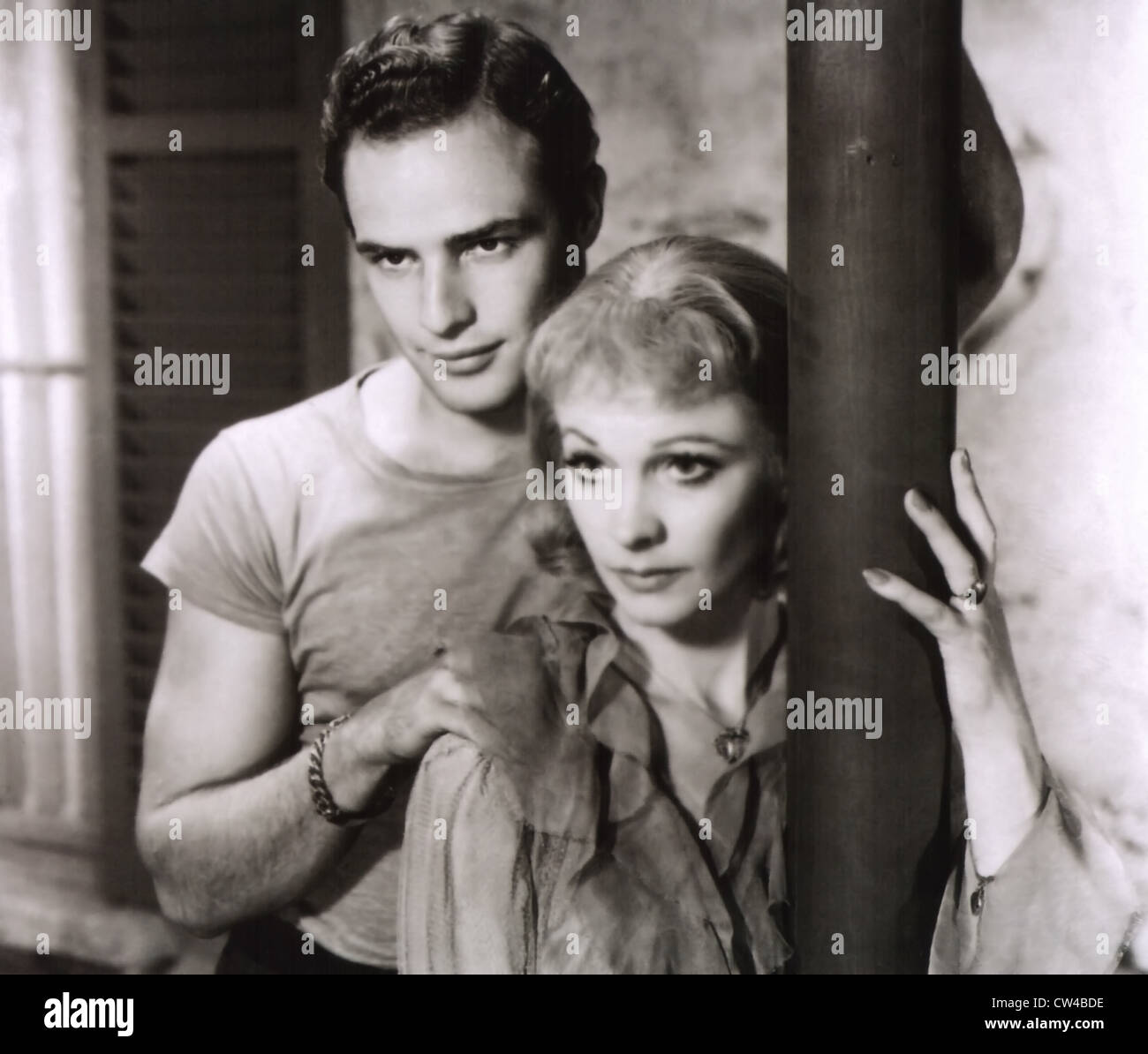

Early audiences sometimes cheered for Stanley because they found Blanche’s elitism annoying. That’s wild when you think about it now. Stanley is a domestic abuser. He’s a predator. But Brando played him with such animal magnetism in the 1951 film adaptation that he blurred the lines for a generation of viewers. Williams was brilliant at this; he made the "villain" charismatic and the "heroine" deeply flawed and sometimes even irritating.

Why the Setting Matters More Than You Think

New Orleans isn't just a backdrop here. It's a character. Specifically, the Elysian Fields neighborhood.

In Greek mythology, the Elysian Fields were the final resting place of the heroic and the virtuous. In Williams' play, it’s a cramped, two-room apartment where people are literally on top of each other. The irony is thick. You have the "Streetcar" named Desire that transfers to one called Cemeteries. It’s not subtle. Life, sex, and death are all tied together in this one transit line.

💡 You might also like: How to Watch The Wolf and the Lion Without Getting Lost in the Wild

If you’ve ever been to the French Quarter in the summer, you know that heat. It’s heavy. It makes people irritable. In the play, that humidity acts like a physical weight, forcing the characters into a state of psychological breakdown. Blanche is constantly bathing. She’s trying to "wash off" her past, her sins, and the grime of the city. Stanley just sweats. He’s comfortable in the dirt.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Ending

The ending of A Streetcar Named Desire is one of the most devastating moments in literature, but it’s often misinterpreted as a simple "madness" arc. When Blanche says she has "always depended on the kindness of strangers," she isn't just being poetic. She’s admitting defeat.

She has spent her whole life trying to find a "gentleman" to save her from the reality of her fading youth and her lost estate, Belle Reve. But the world she lives in doesn't have room for gentlemen anymore. It has Stanleys.

The tragedy isn't just that Blanche "goes crazy." The tragedy is that her sister, Stella, chooses Stanley over her. Stella knows, deep down, that Blanche is telling the truth about Stanley’s assault. But she can't accept it. To accept it would mean losing her husband and her new life. So, she sends her sister away to a mental institution. It’s a betrayal of blood for the sake of survival. It's brutal.

The Censorship Battle of 1951

You can't talk about this play without talking about the movie. Elia Kazan directed both the original Broadway run and the film. But the film had to deal with the Hays Code—the strict censorship rules of the time.

In the play, Blanche’s late husband, Allan Grey, died by suicide after she discovered him with another man. In the 1950s, you couldn't say "homosexuality" on screen. The movie had to dance around it, making it sound like he was just "weak" or "unmanly."

📖 Related: Is Lincoln Lawyer Coming Back? Mickey Haller's Next Move Explained

Even more significant was the ending. In the original play, Stanley gets away with everything. Life goes on. The "New World" wins by crushing the old one. But the censors wouldn't allow a "bad man" to go unpunished. So, in the movie, they added a shot of Stella saying she’s never going back to him. It changed the entire meaning of the story just to satisfy a moral code that didn't exist in Williams' gritty reality.

Tennessee Williams and the Art of the Southern Gothic

Williams was writing from a place of deep personal pain. His sister, Rose, underwent a prefrontal lobotomy that left her incapacitated for the rest of her life. Many scholars, including those at the The Tennessee Williams Annual Review, point out that Blanche’s "shattered" mind is a direct reflection of Rose.

This isn't just fiction; it's an exorcism of family ghosts.

The Southern Gothic genre thrives on this stuff. It’s about the decay of the South, the skeletons in the closet, and the tension between what we pretend to be and who we actually are. A Streetcar Named Desire is the peak of this style. It uses expressionistic elements—like the "Varsouviana" polka music that plays in Blanche's head—to show the audience her internal collapse.

How to Approach the Text Today

If you’re reading or watching it now, look for the power dynamics. It’s not just a "sad story." It’s a study of:

- Social Class: The tension between the declining aristocracy and the rising industrial working class.

- Gender Roles: How Stella and Blanche are forced to navigate a world where they have zero economic power without a man.

- Truth vs. Illusion: Blanche famously says, "I don't want realism. I want magic!" This is the core of her character. She lies not to deceive others, but to make the world bearable for herself.

There is a reason this play is still staged every single year in theaters from London to Tokyo. It taps into a universal fear: the fear that our past will catch up with us and that the world we understand is being replaced by something we can't control.

👉 See also: Tim Dillon: I'm Your Mother Explained (Simply)

Actionable Insights for Theater Lovers and Students

If you want to truly appreciate the depth of A Streetcar Named Desire, don't just read the SparkNotes. Do these three things:

1. Watch the 1951 film, but read the play's ending first.

Compare the two. Notice how the lack of a "punishment" for Stanley in the play makes the story feel much more dangerous and modern. The play’s ambiguity is where the genius lies.

2. Listen to the stage directions.

Tennessee Williams was famous for writing lyrical, almost novel-like stage directions. He describes the "blue piano" and the "lurid reflections" on the walls. These aren't just instructions for actors; they are part of the storytelling. If you’re reading the script, don't skip the italics.

3. Research the "Belle Reve" backstory.

The name translates to "Beautiful Dream." Understanding that Blanche lost her home because of the "epic fornications" of her ancestors gives her character a layer of generational trauma. She isn't just "crazy"; she is the literal end of a bloodline that spent all its capital on vice.

The brilliance of this work is that it doesn't give you an easy out. You leave the theater or close the book feeling a bit greasy, a bit sad, and very aware of the shadows in the corner of the room. That’s the "magic" Blanche was talking about, even if it turned out to be a nightmare.

To understand the modern American theater landscape, you have to start here. You have to understand the scream, the sweat, and the sound of that streetcar rattling through the Quarter. A Streetcar Named Desire isn't just a classic—it’s a warning about what happens when we lose our illusions and have nothing left to replace them.

The next time you see a production, pay attention to the lighting. Blanche hates bright lights because they show the truth of her aging face. We all have our "paper lanterns" that we use to hide the ugly parts of our lives. Williams just had the guts to rip them off.