You’ve felt it. That hot, prickly heat behind your eyes when someone does something truly heinous and gets away with it. It’s not just "being mad." It’s something deeper, more primal. We call it a righteous thirst for vengeance, and honestly, society spends a lot of time telling us to suppress it. We’re told to "be the bigger person" or "let it go." But if you look at the biology and the history of human behavior, you realize that this drive isn't just some character flaw. It’s a mechanism.

Evolution doesn't keep things around that don't serve a purpose. If the desire for retribution was just a "bad" emotion, it would have been weeded out of our gene pool thousands of years ago. Instead, it’s a universal human experience.

The biology of the righteous thirst for vengeance

When we see a wrong committed—especially a violation of social fairness—our brains react in a way that’s almost identical to physical pain. Dr. Tania Singer, a world-renowned neuroscientist, has conducted extensive research on how empathy and fairness activate specific parts of the brain like the anterior insula. When you witness an injustice, your brain screams.

It wants balance.

A 2004 study published in Science by Dominique de Quervain and colleagues used PET scans to see what happens when people punish those who have acted unfairly. The results were wild. The striatum—the part of the brain responsible for processing rewards and pleasure—lit up like a Christmas tree. Basically, our brains are hardwired to find satisfaction in seeing "bad" people get what’s coming to them. It’s a dopaminergic hit.

This isn't about being a "bad person." It's about "altruistic punishment."

Think about it. In a small tribe 50,000 years ago, if one person stole everyone’s food and nobody did anything, the whole tribe would die. The thirst for vengeance acted as a deterrent. It was the original legal system before we had courthouses and gavels. If you knew that stealing my goat would result in a righteous, focused attempt to get even, you probably wouldn't steal the goat. It’s a social stabilizer.

Why we confuse justice with revenge

We like to pretend there’s a massive wall between "justice" and "vengeance." There isn't. Justice is just vengeance with a suit and tie on. It’s the institutionalized version of that same primal urge.

The legal philosopher Robert Nozick once argued that there are distinctions, sure. Vengeance is personal; justice is impersonal. Vengeance is often excessive, while justice seeks a specific scale of "an eye for an eye." But the root is the same: the belief that a moral debt has been incurred and it must be paid.

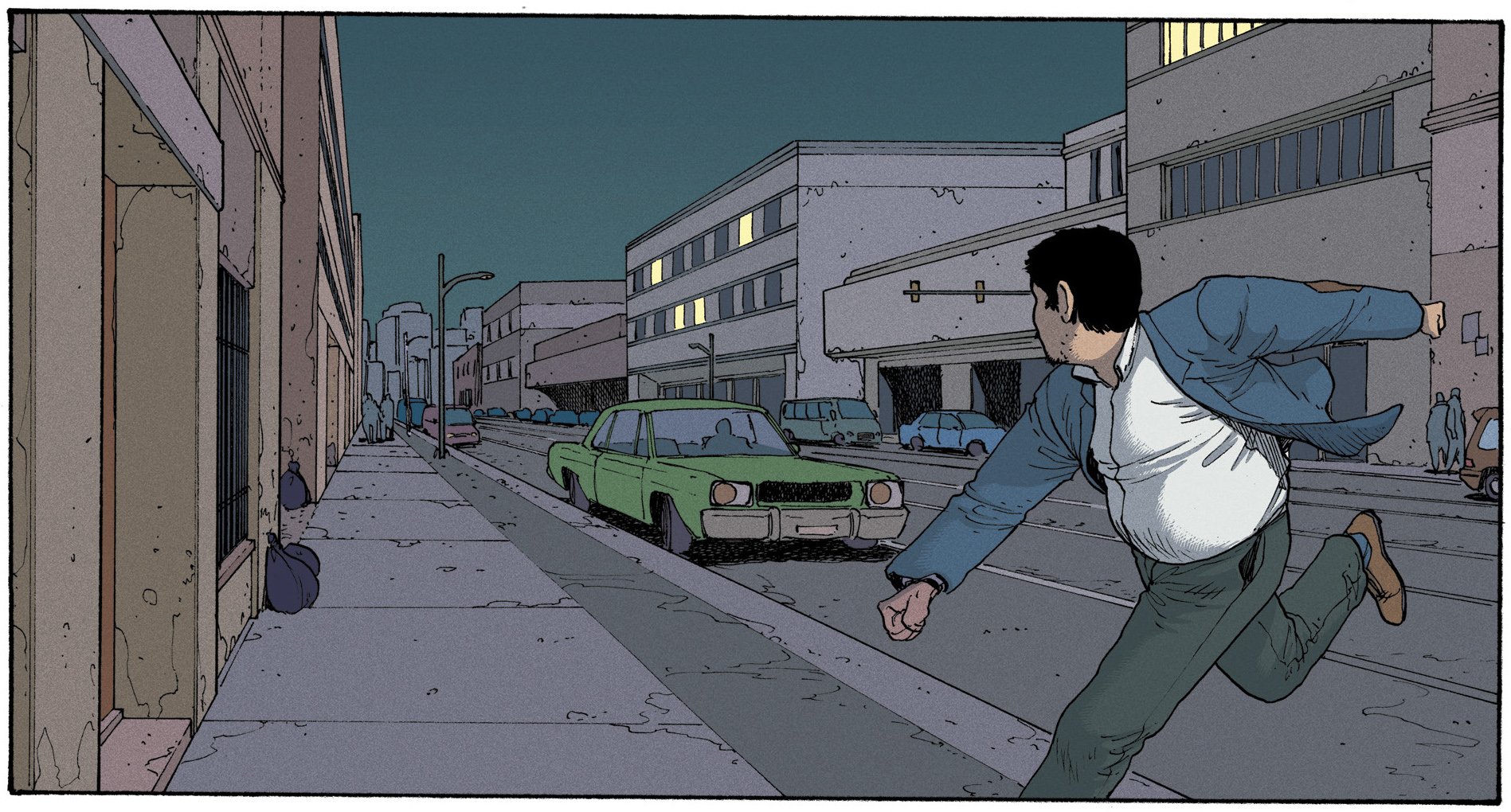

Sometimes the system fails. We see it in the news every single day. When the official channels of justice break down, that's when the righteous thirst for vengeance shifts from a background hum to a roar. People start looking for ways to settle the score themselves because the "social contract" has been breached. If the state won't protect the innocent or punish the guilty, the individual feels a moral imperative to do it.

✨ Don't miss: Garden State Tolls Calculator: How to Actually Budget for Your Next Jersey Shore Drive

The psychological cost of letting it go

There is a popular narrative in modern self-help that "forgiveness is for you, not for them." That's a nice sentiment. It really is. But for some people, forced forgiveness feels like a second assault.

Psychologist Dr. Kevin Carlsmith has spent years studying the "paradox of revenge." His research suggests that while we think revenge will make us feel better, it sometimes keeps the wound open longer because we stay focused on the offender. However—and this is a big "however"—there is also evidence that "victim empowerment" is a real thing.

When a person who has been victimized regains a sense of agency, their mental health improves. Sometimes, that agency comes through seeing the perpetrator held accountable. If "letting it go" means "accepting that the world is unfair and I am a doormat," then letting it go is actually psychologically damaging. It leads to learned helplessness.

Real world examples of the drive for retribution

Look at the story of Marianne Bachmeier. In 1981, in a West German courtroom, she pulled out a pistol and shot the man who had murdered her seven-year-old daughter. She didn't wait for the verdict. She didn't trust the system. The public reaction at the time was fascinating—there was a massive wave of sympathy for her. People recognized her righteous thirst for vengeance as a natural, almost holy, response to an unthinkable crime.

Or consider the "Nakam" group after World War II. These were Jewish Avengers—literally, that’s what they called themselves—who sought to kill Nazis who had escaped the Nuremberg trials. They weren't looking for "closure." They were looking for a literal rebalancing of the scales.

👉 See also: Why Everyone Is Obsessed With the Cropped Black Fur Jacket Right Now

The danger of the feedback loop

We have to talk about the dark side, though. Vengeance is like a drug. The first hit feels like justice, but it’s rarely enough.

In many cultures, "blood feuds" have lasted for centuries. The Hatfields and the McCoys. The Highland clans of Scotland. The problem with a righteous thirst for vengeance is that the other side usually thinks their retaliation is righteous too. Everyone is the hero of their own story. Everyone thinks they are the ones "settling the score," which means the score is never actually settled. It’s just a math problem that never reaches zero.

This is why we created the legal system. We realized that as humans, we are terrible at being objective about our own pain. We need a third party to step in and say, "Okay, this is enough."

How to handle the thirst without losing your soul

If you are sitting there right now, vibrating with the need to get even, you need to categorize what you're feeling. Is this a desire for restoration or destruction?

Restoration is about making things right. It’s about getting your money back, getting an apology, or ensuring the person can never hurt anyone else again. Destruction is just about causing pain.

- Check the "Debt": Is the person you're mad at actually capable of "paying" the debt? If you’re waiting for a narcissist to apologize, you’re waiting for a dead man to speak. They don't have the currency you're looking for.

- The "Wait" Rule: The brain's reward center (the striatum) wants immediate satisfaction. The prefrontal cortex (the logic center) wants long-term safety. If you still feel the same thirst for vengeance after 30 days of no contact, it’s likely a deep-seated moral issue rather than a temporary temper tantrum.

- Sublimation: This sounds like some Freud nonsense, but it works. Take that energy and turn it into something that makes the offender’s actions irrelevant. Success is the "best" revenge not because it hurts them, but because it proves they didn't have the power to break you.

- Legal and Social Channels: Exhaust these first. Even if they feel slow and inadequate. Documentation is your best friend. A well-placed, factual HR report or a civil lawsuit is a form of vengeance that doesn't end with you in a jail cell.

Moving forward with a clear head

Understand that feeling a righteous thirst for vengeance doesn't make you a monster. It makes you a human with a functioning sense of morality. You are reacting to a breach in the way the world is supposed to work.

🔗 Read more: Lusso Self-Tanning Mousse Travel Size: Why Your Vacation Glow Usually Fails

The goal isn't necessarily to "forgive and forget." The goal is to reach a point where the person who wronged you no longer occupies the primary real estate in your brain.

Actionable steps for when the rage hits

- Write the "Grievance List": Write down exactly what was taken from you. Not just "money" or "time," but "respect," "safety," or "trust."

- Identify the "Anti-Goal": What would "losing" look like here? Usually, losing looks like you becoming a bitter, stagnant version of yourself because you're obsessed with the other person.

- Create a "Vengeance Alternative": If you can't get legal justice, find a way to help someone else who is in the position you were in. It’s a way of "punishing" the injustice itself rather than the specific individual.

- Limit the Audience: Don't vent your thirst for vengeance on social media. It creates a record that can be used against you and often makes you look like the aggressor. Keep your circle tight.

The thirst for vengeance is a fire. It can keep you warm and give you the energy to fight for yourself, or it can burn your house down. The trick is knowing when to stoke the flames and when to let the embers die out so you can finally get some sleep.