Ever tried to swallow a piece of dry toast and felt that weird, scratchy sensation right behind your breastbone? That's the moment most people start thinking about their internal plumbing. When you look at a picture of the esophagus and trachea, it basically looks like two garden hoses sitting side-by-side in your neck and chest. But honestly, it’s way more complicated than that. These two tubes are neighbors, sure, but they have completely different jobs, different textures, and a very specific "don't touch" policy when it comes to the substances they carry.

One carries your lunch. The other carries your life—air.

If you’re staring at a medical diagram or a high-res cross-section, you’ll notice they aren't just floating there. They’re tightly packed. The trachea, or windpipe, sits right in front. It’s the tough guy of the duo, reinforced with these rigid, C-shaped rings of cartilage. Behind it, almost hiding, is the esophagus. It’s floppy. It’s muscular. It stays collapsed until you actually swallow something. Understanding this layout isn't just for med students; it’s literally the difference between a normal dinner and a frantic call to emergency services because someone "swallowed down the wrong pipe."

The Anatomy of the Neighborhood

When you see a picture of the esophagus and trachea from a lateral (side) view, the first thing that jumps out is the proximity. They share a wall. This is called the tracheoesophageal party wall. It’s a thin layer of connective tissue, and while it’s usually sturdy, it’s also where things can go wrong, like in cases of tracheoesophageal fistulas where a hole develops between the two.

The trachea is built for one thing: keeping the airway open at all costs. Think of it like a vacuum cleaner hose. If it were soft and squishy, every time you took a deep breath, the pressure would suck the walls shut and you'd suffocate. To prevent that, the body uses those 16 to 20 cartilage rings. Interestingly, these rings aren't full circles. They are C-shaped, with the open part of the "C" facing backward.

Why? Because the esophagus needs room to expand.

When you bolt down a large bite of a burger, the esophagus has to stretch to accommodate that bolus of food. Since it sits directly behind the trachea, it actually pushes into that soft, back part of the windpipe. If the trachea had full circular rings of bone-hard cartilage, you’d probably choke or feel intense pain every time you ate something larger than a pea. The design is a compromise between structural integrity for breathing and flexibility for eating.

✨ Don't miss: The Truth Behind RFK Autism Destroys Families Claims and the Science of Neurodiversity

Mapping the Upper Gateway: The Larynx and Epiglottis

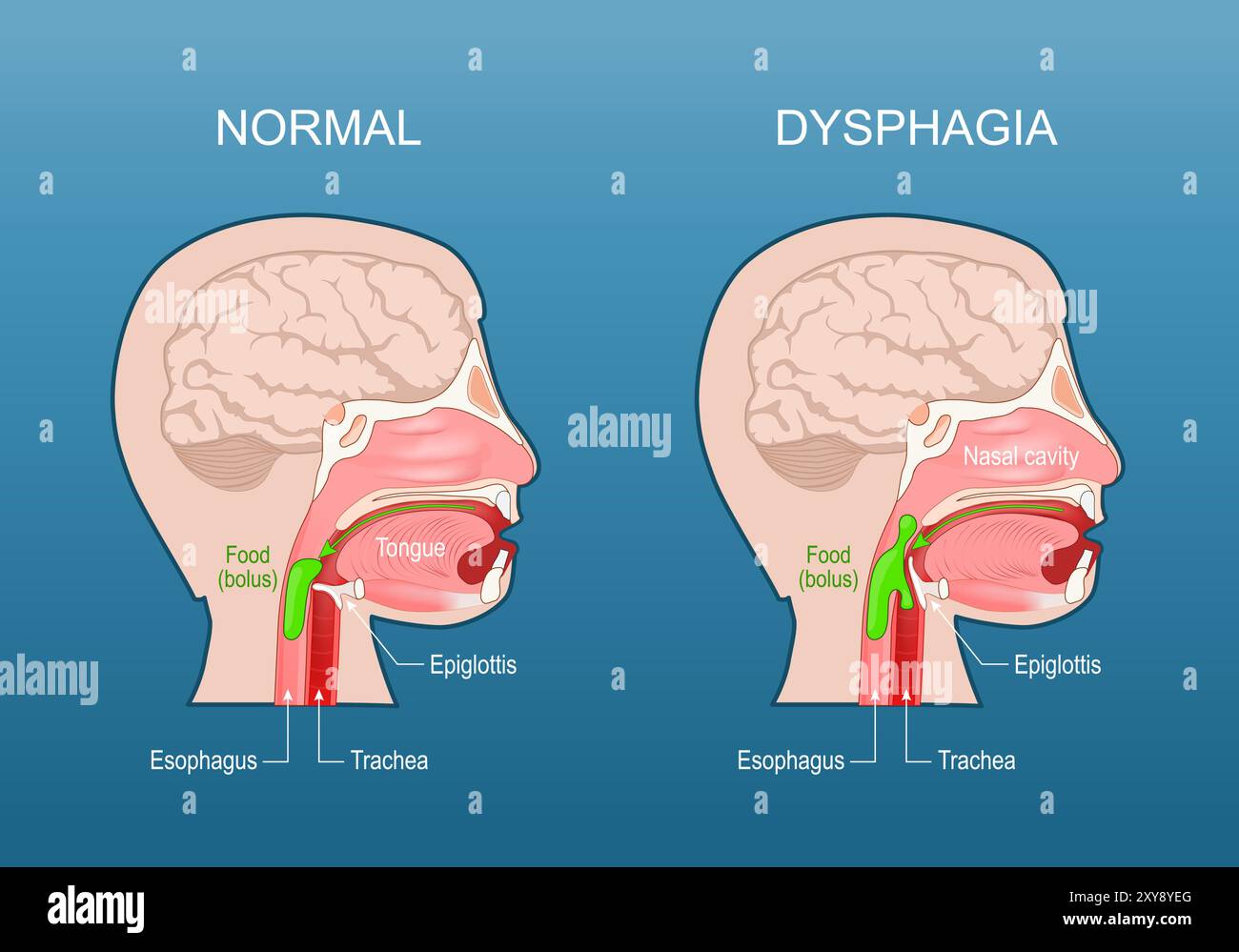

You can't really talk about a picture of the esophagus and trachea without mentioning the bouncer at the door: the epiglottis. This little leaf-shaped flap of cartilage is the most important traffic controller in your body.

Most of the time, the epiglottis stands upright. This allows air to flow freely into the larynx and down the trachea. But the second the swallowing reflex kicks in, the epiglottis flips down like a trapdoor. It seals off the trachea so that the wine or steak you're enjoying slides over the top and into the esophagus instead.

Sometimes the timing is off.

Maybe you laughed while drinking water. That "wrong pipe" sensation is literally the epiglottis failing to close fast enough, allowing liquid to hit the sensitive lining of the trachea. The result? A violent, reflexive cough. This is your body’s "eject" button. The trachea is lined with tiny hairs called cilia and mucus-producing cells. Their whole mission is to sweep out anything that isn't air.

What Real Medical Imaging Shows

If you move away from textbook illustrations and look at a picture of the esophagus and trachea through an endoscopy or a CT scan, the reality is much messier and more fascinating.

- On a CT scan (the "bird's eye view" from the feet up), the trachea looks like a clear, black circle because it’s full of air. The esophagus often looks like a small, flat slit right behind it, sometimes barely visible unless there's food or a bit of air trapped in it.

- During an endoscopy—where a camera goes down the throat—the esophagus looks like a pink, moist tunnel with circular folds of muscle. It’s dynamic. You can see it pulsing with peristalsis, the wave-like contractions that push food down to the stomach.

- A bronchoscopy, which looks down the trachea, shows a much different world. The walls are white and rigid because of the cartilage, and the "floor" of the tube is actually the soft tissue it shares with the esophagus.

Doctors like Dr. Jonathan Aviv, a renowned ENT and author, often point out that the health of one affects the other. For instance, chronic acid reflux (GERD) doesn't just stay in the esophagus. The acid can actually "spill over" the top and irritate the larynx and trachea, leading to a chronic cough or even "silent reflux" symptoms that mimic asthma.

🔗 Read more: Medicine Ball Set With Rack: What Your Home Gym Is Actually Missing

Misconceptions People Have About These Tubes

A lot of people think the esophagus is just a gravity-fed slide. It’s not. You can actually eat while standing on your head (not recommended, but possible) because the muscles are that strong. The trachea, however, is a passive pipe. It doesn't "pump" air; your diaphragm and chest muscles do that work.

Another big one? The idea that they are the same size.

Actually, the trachea is usually wider, about an inch in diameter in most adults. The esophagus is roughly the same length—about 25 centimeters—but its width varies wildly depending on whether you’re resting or swallowing a Thanksgiving feast.

When the Two Pipes Get "Crossed"

There are specific medical conditions that only make sense when you see a picture of the esophagus and trachea together. One is "aspiration." This happens when the separation fails. In elderly patients or those with neurological issues, the coordination between the epiglottis and the esophagus weakens. Food "aspirates" into the trachea, which can lead to aspiration pneumonia. This is why speech-language pathologists (SLPs) are so obsessed with the "swallow study"—they are literally watching a live X-ray (fluoroscopy) to see if liquid is heading for the "front pipe" instead of the "back pipe."

Then there's the "Esophageal Twitch" or spasms. Sometimes the esophagus decides to cramp up. Because it's so close to the heart and the trachea, this pain is often mistaken for a heart attack. It’s a crushing sensation right in the middle of the chest. It’s only by looking at the specific anatomy that doctors can differentiate between a cardiac event and an esophageal one.

Practical Insights for Better Health

So, what do you do with this knowledge? Understanding the layout of your throat can actually change how you live.

💡 You might also like: Trump Says Don't Take Tylenol: Why This Medical Advice Is Stirring Controversy

Don't talk with your mouth full. This isn't just about manners. Talking requires air to move up through the trachea. Eating requires the epiglottis to stay down. When you try to do both, you’re essentially forcing the epiglottis to stay open while food is present. It’s a recipe for choking.

Watch your posture while eating. If you're hunched over your phone, you're compressing the space where the esophagus and trachea reside. This can make swallowing less efficient and increase the likelihood of acid reflux, as the stomach is squeezed and its contents are pushed up against the lower esophageal sphincter.

Hydration matters for both. The trachea needs a thin layer of mucus to trap dust. If you're dehydrated, that mucus gets thick and sticky, leading to that "need to clear my throat" feeling. The esophagus needs saliva to help lubricate the bolus of food for a smooth trip down.

Recognize the "Lump in the Throat." This is a real thing called "globus pharyngeus." Often, it’s not a physical blockage but a tension in the muscles of the esophagus or irritation from acid. Knowing that the esophagus is a muscular tube that reacts to stress can help you realize that the "lump" might just be your body's way of saying you're overwhelmed.

Key Takeaways for the Next Time You See a Diagram

- Front vs. Back: The trachea is always in the front (ventral); the esophagus is in the back (dorsal).

- Structure: Trachea = hard/cartilage; Esophagus = soft/muscular.

- The Shared Wall: They are physically connected, which is why issues in one (like a massive tumor or severe inflammation) can sometimes press on and affect the other.

- The Epiglottis is King: This tiny flap is the only thing standing between a peaceful meal and a medical emergency.

If you’re experiencing persistent trouble swallowing, a chronic cough that won't quit, or a feeling of "fullness" in your chest, it’s usually time to see a gastroenterologist or an ENT. They use tools like the "barium swallow" where you drink a chalky liquid that shows up on X-rays, providing a clear picture of the esophagus and trachea in motion. This allows them to see exactly where the "traffic jam" is happening.

Take care of these two tubes. They are the primary gateways for everything your body needs to survive. Without a clear trachea, you can't breathe; without a functional esophagus, you can't fuel. Keeping them healthy is mostly about eating mindfully, staying hydrated, and not ignoring the signals—like heartburn or a nagging cough—that something in the neighborhood might be wrong.