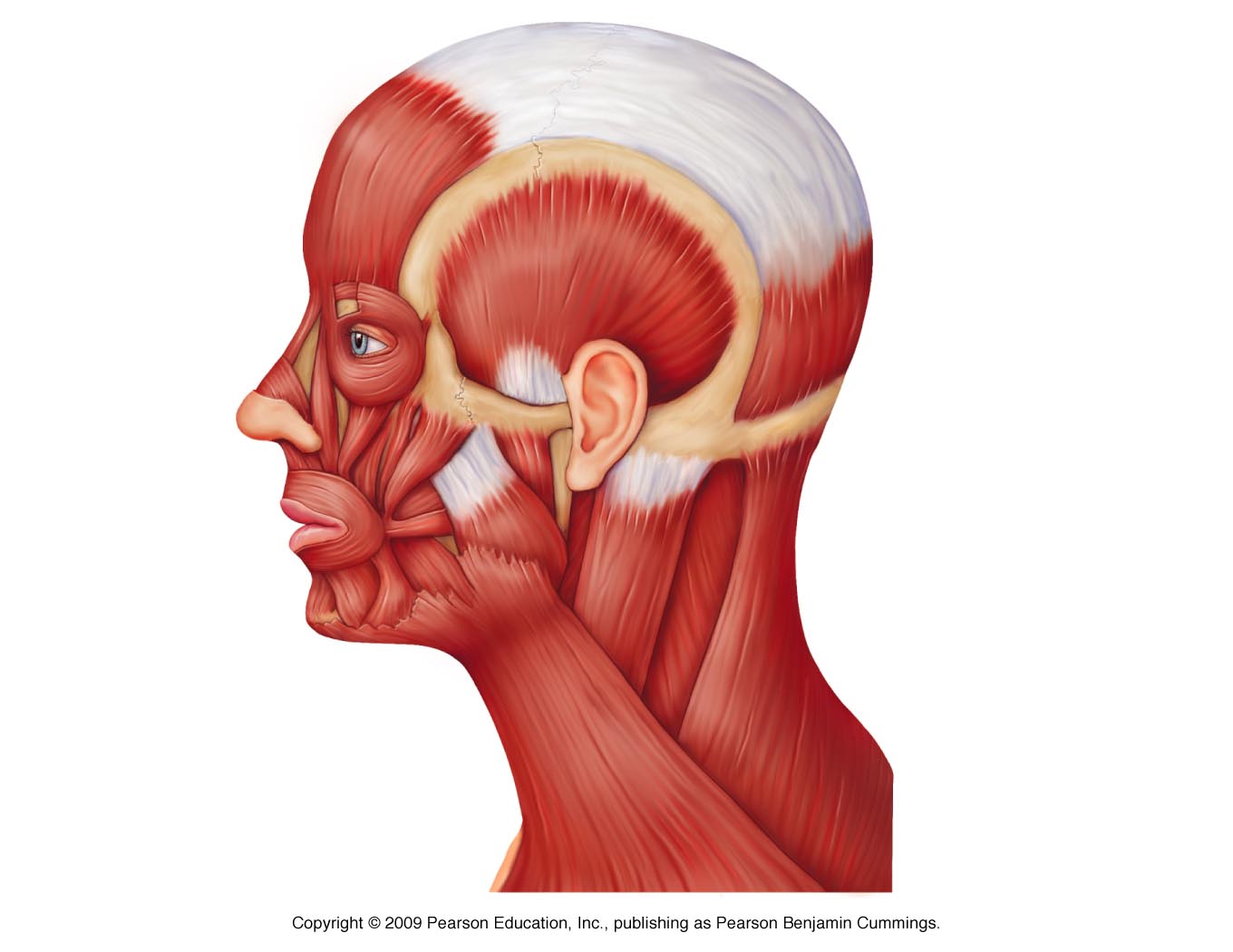

You’ve seen it before. That classic, slightly unsettling picture of facial muscles with the red-stripped fibers and the hollowed-out eyes. It’s a staple in every doctor’s office and biology classroom. But honestly, most of those diagrams are lying to you—or at least, they’re oversimplifying things to the point of being misleading.

The human face is a chaotic masterpiece. It’s the only place in your entire body where muscles don’t just bone-to-bone; they actually stitch themselves directly into your skin. That’s why you can wink, sneer, or look genuinely surprised when you realize your "healthy" smoothie has 60 grams of sugar. If those muscles only moved bones, your face would be as expressive as a mannequin.

Understanding the layout isn't just for surgeons. It’s for anyone who’s ever wondered why their forehead wrinkles a certain way or why "tech neck" is making their jawline look soft.

The Graphic Reality of the Picture of Facial Muscles

When you look at a standard picture of facial muscles, you’re usually seeing about 40 to 50 individual muscles. The exact number is actually debated among anatomists because some of these muscle groups are so deeply intertwined it’s hard to tell where one ends and another begins. It’s not like the bicep, which is a discrete, easy-to-find hunk of meat. Facial muscles are thin, flat, and often incredibly delicate.

Take the orbicularis oculi. That’s the ring of muscle around your eye. In most diagrams, it looks like a simple circle. In reality, it’s a sophisticated shutter system. It has different parts—one for gentle blinking and another for "scrunching" your eyes shut against the wind. When you see a high-res image of this, you’ll notice the fibers radiating outward. This is exactly why crow’s feet form perpendicular to those fibers over time. It’s basic physics.

The Smile Mechanics You Won’t See in a 2D Drawing

Most people think "smiling" is just one movement. It's not. It's a tug-of-war. You have the zygomaticus major, which is the "big" smile muscle that pulls the corners of your mouth up and out. But then there’s the risorius, a tiny, often-ignored muscle that pulls the corners laterally.

If you’ve ever seen a "fake" smile where the mouth moves but the eyes don’t, you’re seeing a failure of muscle coordination. A Duchenne smile—the real deal—requires the orbicularis oculi to contract simultaneously with the zygomaticus major. You can't really fake that easily because the eye muscles are harder to control voluntarily for most folks.

🔗 Read more: Creatine Explained: What Most People Get Wrong About the World's Most Popular Supplement

Why 3D Mapping is Replacing the Static Picture of Facial Muscles

Static images are becoming obsolete in high-end medical training. Researchers like those at the Mayo Clinic or specialists in maxillofacial surgery now use dynamic 3D mapping. Why? Because a flat picture of facial muscles fails to show depth.

The face is layered. You have superficial muscles right under the skin and deep muscles tucked behind them. The buccinator, for example, is deep in your cheek. Its job isn't even about expression, mostly; it keeps your food between your teeth while you chew so you don't bite your own cheek. If you’re looking at a basic diagram, the buccinator is often buried under the masseter, which is the powerhouse muscle responsible for clenching your jaw.

Fun fact: The masseter is, pound for pound, the strongest muscle in the human body. Not the glutes. Not the quads. The jaw. You can exert over 200 pounds of force on your molars. Think about that next time you’re stressed and grinding your teeth at 3:00 AM.

The SMAS Layer: The Secret to Modern Facelifts

If you’ve ever looked into plastic surgery or "tweakments," you’ve likely heard of the SMAS (Superficial Musculoaponeurotic System). You won't find this labeled on a cheap picture of facial muscles you find on a stock photo site.

The SMAS is a fibrous envelope that connects your facial muscles to each other. It’s like a structural web. When surgeons perform a "deep plane" facelift, they aren't just pulling the skin. They are repositioning this SMAS layer. If you just pull the skin, you get that "windblown" look that everyone wants to avoid. By moving the muscle-connective tissue as a unit, the result looks like a person, not a taut drum.

Gravity, Aging, and Muscle Memory

There is a common myth that facial exercises—often called "face yoga"—can act like a natural facelift. The logic seems sound: if you work out your quads, your legs get tighter. So if you work out your face, your skin should lift, right?

💡 You might also like: Blackhead Removal Tools: What You’re Probably Doing Wrong and How to Fix It

Well, it's complicated.

Because facial muscles are attached to the skin, overworking them can actually increase wrinkles. Think about the frontalis, the large muscle on your forehead. Its only job is to lift your eyebrows. Every time it contracts, it bunches the skin above it. A lifetime of lifting your eyebrows results in those deep horizontal forehead lines. Doing "reps" of eyebrow raises is just fast-tracking those wrinkles.

However, some tension is good. Muscles like the procerus (between your eyebrows) and the corrugator supercilii (the "frown" muscles) often hold chronic tension from stress. This is why people get Botox. Botox doesn't fix the skin; it temporarily paralyzes the muscle so it stops bunching the skin. It's literally a chemical way to "ignore" the muscle fibers you see in that anatomy picture.

The Platysma: The "Grief" Muscle

The platysma is a massive, thin sheet of muscle that runs from your jawline down to your collarbones. In a standard picture of facial muscles, it looks like a bib. It’s often called the muscle of grief because it pulls the corners of the mouth down and tightens the neck when you’re distressed.

Modern "tech neck" is wreaking havoc on the platysma. When we stare down at phones, we shorten this muscle. Over time, this contributes to "turkey neck" and a loss of jawline definition. Looking at a diagram of the platysma makes it clear: it’s a giant tension sheet. If it’s tight, everything above it gets pulled down.

Beyond the Basics: Muscles You Didn’t Know You Had

Most people can name the jaw or the forehead. But have you heard of the depressor septi nasi? It’s a tiny little thing right under your nose. For some people, when they talk or smile, the tip of their nose pulls downward. That’s this muscle at work. Surgeons sometimes snip it or Botox it just to keep the nose "perky."

📖 Related: 2025 Radioactive Shrimp Recall: What Really Happened With Your Frozen Seafood

Then there’s the mentalis. It’s the muscle on your chin. If you’ve ever seen someone about to cry and their chin gets all "pebbly" or dimpled like an orange peel, that’s the mentalis contracting. It’s an incredibly expressive little muscle that most people don't even realize they're using.

Variation is the Rule, Not the Exception

Here is the thing about every picture of facial muscles you’ll ever see: it represents a "standard" human. But humans are rarely standard.

Some people are born without certain muscles. The risorius (the grinning muscle) is actually missing in a significant chunk of the population. Some people have "split" muscles that allow them to dimple their cheeks. Dimples aren't a special "beauty feature" in terms of extra parts; they are actually caused by a bifid (split) zygomaticus major muscle. The skin gets caught in the gap between the two muscle bundles. It’s technically an anatomical variation, but we’ve decided it’s cute.

How to Use This Knowledge Practically

If you’re staring at a picture of facial muscles trying to figure out your own face, don't just look at the red bits. Look at the directions the fibers run.

- Massage Direction: If you’re using a Gua Sha or just your fingers, always move in the direction of the muscle fibers or upward against gravity. For the cheeks, move toward the ears. For the forehead, move toward the hairline.

- Postural Awareness: Realize that your jaw muscles (masseter) are connected via fascia to your neck and shoulders. If your jaw is tight, your neck will be too.

- Sun Protection: Since facial muscles are so thin, the skin above them needs to stay elastic to handle the constant movement. UV damage breaks down collagen, meaning your skin can't "snap back" after the muscle moves it.

- Eye Care: Be extremely gentle around the orbicularis oculi. The skin there is the thinnest on the body, and the muscle underneath is constantly active (we blink about 15,000 times a day).

Actually, the best way to understand your facial anatomy isn't by looking at a book. It’s by making the most ridiculous faces you can in a mirror. Watch how your skin bunches. Feel where the tension sits. That’s your personal anatomy lesson, far more accurate than any static 2D print could ever be.

To take this further, start by identifying your "tension spots." Place your fingers on your jaw hinges and clench your teeth; you'll feel the masseter bulge. That is the muscle most people need to "release" to reduce facial puffiness and headaches. Next, try to lift only one eyebrow. If you can't, you're seeing your neural pathways and muscle isolation (or lack thereof) in real-time. This awareness is the first step in managing everything from aging to chronic jaw pain without jumping straight to expensive clinical interventions.