You’re probably here because you’ve got a weird lump in your throat, or maybe you’re just a student trying to figure out why humans choke so easily compared to other animals. It’s a design flaw. Seriously. If you look at a picture of esophagus and trachea side-by-side, the first thing you notice is how dangerously close they are. They share a wall. They're roommates that don't always get along.

Most people think of the throat as one big pipe. It isn't. You actually have two distinct tubes running down your neck, and they have completely different jobs, textures, and structural engineering.

The trachea is the tough guy. It's built like a vacuum cleaner hose with these rigid, C-shaped rings of cartilage. You can actually feel them if you run your fingers down the front of your neck. It has to stay open. If the trachea collapses, you stop breathing, and things get very bad very quickly. On the flip side, the esophagus is a floppy, muscular tube that stays collapsed until you actually swallow something. It’s more like a sock than a pipe.

The Anatomy Reality: What You're Actually Seeing

When you look at a high-quality medical picture of esophagus and trachea, the most striking part is the "stripping" on the trachea. Those cartilage rings aren't complete circles. They are C-shaped. Why? Because the open part of the "C" faces the back, right where it touches the esophagus. This is a brilliant bit of biological space-saving. When you bolt down a huge piece of dry pizza, the esophagus needs room to expand. Since the back of the trachea is soft tissue rather than hard bone or cartilage, the esophagus can bulge forward into that space momentarily as the food moves down.

It’s tight in there.

The trachea (windpipe) sits anteriorly—that’s medical speak for "in front." The esophagus sits posteriorly, or "behind." If you were to look at a cross-section, like a slice of deli meat, you’d see the trachea as a sturdy arch and the esophagus as a flattened slit tucked right behind it.

The Epiglottis: The Traffic Cop

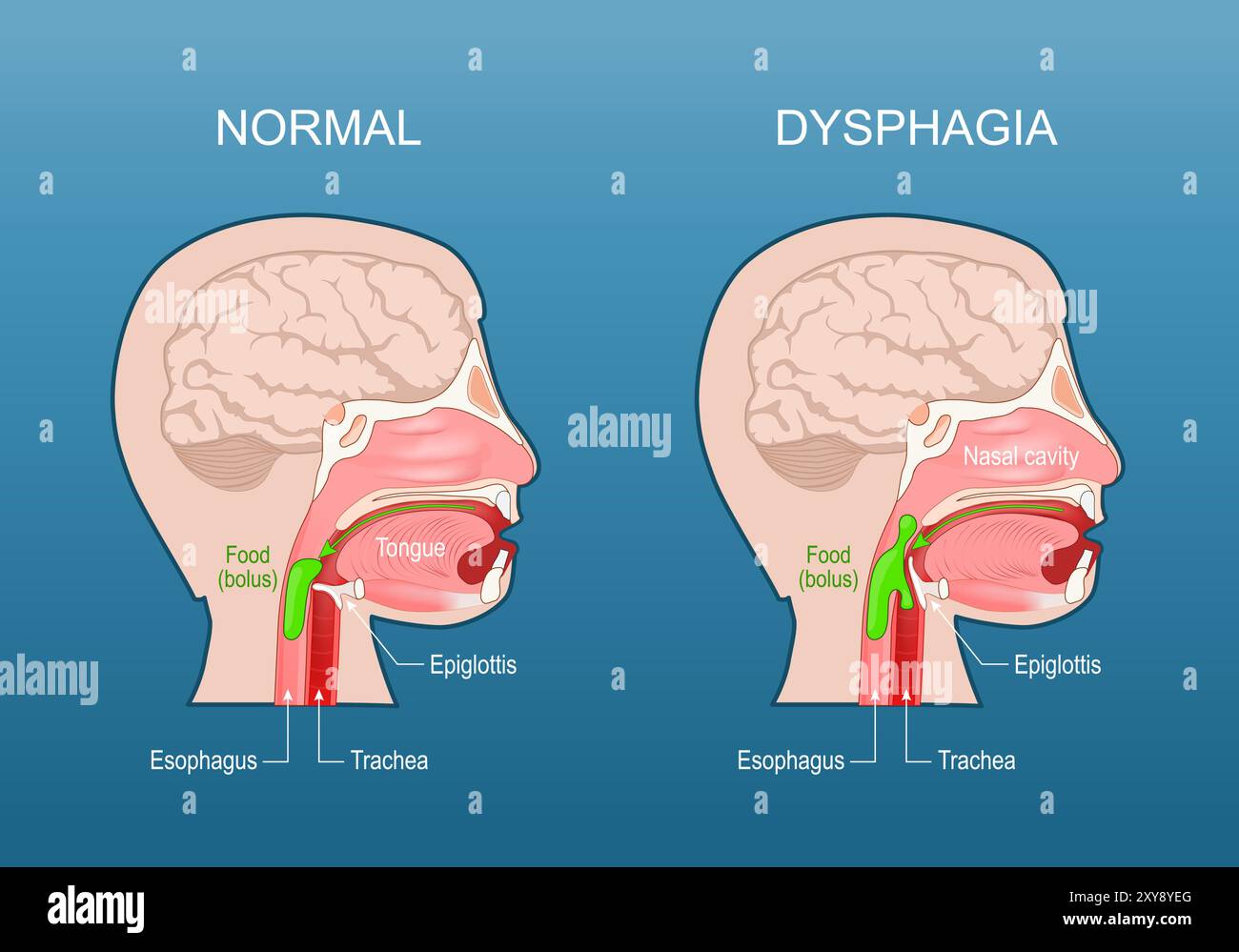

We have to talk about the epiglottis because it’s the hero of every picture of esophagus and trachea discussion. It’s a little flap of elastic cartilage at the root of the tongue. Every time you swallow, this flap flips down like a trapdoor to cover the opening of the trachea.

📖 Related: Whooping Cough Symptoms: Why It’s Way More Than Just a Bad Cold

It’s not a perfect system.

Sometimes you laugh while drinking water, the timing gets wonky, and liquid slips past the gate. That's when you start coughing uncontrollably. Your body is basically panicking to eject the fluid before it hits the lungs. In a clinical setting, doctors use a laryngoscope to see this area. If you’ve ever seen a "view from the top" photo, you’ll see the vocal cords sitting right at the entrance of the trachea, looking like two white rubber bands. The esophagus is that dark, unassuming hole just behind them.

Why the Texture Matters

The lining of these two tubes couldn't be more different.

The trachea is lined with ciliated pseudostratified columnar epithelium. That is a mouthful, I know. Basically, it’s a carpet of tiny hairs called cilia covered in a layer of mucus. This "mucociliary escalator" is constantly moving, sweeping dust and bacteria up and out of your lungs so you can cough it out or swallow it. It's a cleaning machine.

The esophagus? It uses stratified squamous epithelium. It’s tough. It’s designed to handle the friction of rough food, the heat of coffee, and the occasional splash of stomach acid. It doesn’t have hairs. It has muscles—lots of them. The upper third of the esophagus is skeletal muscle (voluntary, sort of), while the bottom third is smooth muscle (automatic). This transition is why you can "feel" a swallow start, but once it gets halfway down, it's out of your hands.

Common Misconceptions Found in Images

A lot of diagrams simplify things so much they actually become misleading. You might see a picture of esophagus and trachea where they look like two garden hoses sitting an inch apart. In reality, they are literally pressed against each other. There is a thin layer of connective tissue between them, but for all intents and purposes, they are a single functional unit in the neck.

👉 See also: Why Do Women Fake Orgasms? The Uncomfortable Truth Most People Ignore

- The Trachea isn't straight: It actually tilts slightly to the right as it heads toward the lungs.

- The Esophagus isn't a slide: Food doesn't just fall down. A process called peristalsis—waves of muscular contraction—pushes food down. You can actually swallow water while standing on your head because of this, though I wouldn't recommend it.

- The "Adam's Apple": This is actually the thyroid cartilage protecting your larynx (voice box), which sits right on top of the trachea. Men usually have a more prominent one because their voice boxes grow larger during puberty, changing the angle of the cartilage.

When Things Go Wrong: Clinical Importance

Understanding these structures isn't just for anatomy nerds. It has massive real-world implications. Take Tracheoesophageal Fistula (TEF), for example. This is a birth defect where an abnormal connection forms between the esophagus and the trachea. Instead of two separate pipes, there’s a "leak" between them. When a baby tries to swallow milk, it ends up in their lungs. You can see this clearly on an X-ray with contrast dye—it’s a terrifying thing for parents, but luckily, surgeons are incredibly good at fixing it these days.

Then there's Intubation. When someone is in the ER and can't breathe, a medic has to slide a tube into the trachea. If they accidentally put it in the esophagus—which is easy to do because it's right there—the patient's stomach will inflate with air instead of their lungs inflating with oxygen. This is why doctors use a CO2 detector; the stomach doesn't breathe out carbon dioxide, but the lungs do.

And we can't forget GERD (Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease). While this is mostly an esophagus problem, the proximity to the trachea is why people with severe acid reflux often have a chronic cough or even asthma-like symptoms. The acid literally irritates the neighborhood.

Evolution's Weird Choice

Biologists often point to the layout of the esophagus and trachea as proof that evolution is a "tinkerer," not a "designer." In fish, the gut and the gills are separate. But as we moved onto land and developed lungs, the plumbing got crossed. We have to pass our food right over the entrance to our airway.

Dolphins and whales don't have this problem. Their blowhole connects directly to their lungs, and their mouth connects to their stomach. They can't choke on their lunch. Humans, however, traded that safety for the ability to use our throat and mouth for complex speech. We can shape sounds because our larynx is low in the throat, but that's exactly what creates the choking hazard.

Basically, we can talk because we are at risk of choking. It’s a weird trade-off.

✨ Don't miss: That Weird Feeling in Knee No Pain: What Your Body Is Actually Trying to Tell You

Looking at Modern Imaging

If you're looking at a picture of esophagus and trachea from a modern CT scan or an MRI, the colors won't be pink and red like in a textbook. You'll see shades of gray. Air looks black. So, the trachea usually shows up as a prominent black circle or oval because it's full of air. The esophagus often looks like a faint gray line or a small "star" shape because it’s collapsed.

Doctors also use something called a Barium Swallow. You drink a chalky liquid that shows up bright white on an X-ray. It's the best way to see the internal "map" of the esophagus and check for any narrowing or blockages.

Actionable Takeaways for Throat Health

If you're worried about your throat or just curious about how to keep these pipes working well, there are a few things you can actually do. First, pay attention to how you swallow. If you feel like things are "catching" or you're coughing every time you drink, that's not normal. It’s called dysphagia, and it’s worth a trip to an ENT (Ear, Nose, and Throat doctor).

Second, watch the acid. Chronic reflux doesn't just "burn"—it can actually change the cells in your esophagus, a condition called Barrett's Esophagus. Because the esophagus and trachea are so close, that inflammation can migrate.

- Hydrate: Mucus in the trachea needs to be thin to move junk out of your lungs. Dehydration makes it sticky and hard to clear.

- Chew thoroughly: It sounds like something your grandma would say, but the esophagus has "pinch points"—natural narrowings (like where the aorta crosses it). Large, unchewed chunks of food are most likely to get stuck at these specific spots.

- Posture matters: Swallowing is a mechanical process. Tucking your chin slightly can actually make the "trapdoor" of the epiglottis work more effectively if you're having trouble.

- Listen to your cough: A "barky" cough usually involves the trachea or larynx. A "wet" cough that feels like it's coming from behind your breastbone might involve the lower esophagus or deep lungs.

The next time you see a picture of esophagus and trachea, don't just see two tubes. See a high-stakes, tightly packed, biological masterpiece that allows you to breathe, eat, and talk all at once—even if it is a little bit prone to accidents. Knowing where the "pipes" are and how they interact is the first step in understanding why your body does what it does when you take a bite of food or a breath of air.

To get a better sense of your own anatomy, try this: place your fingers on your "Adam's Apple" and swallow. You'll feel the whole larynx and trachea structure move upward. This movement is what allows the epiglottis to fold down and the esophagus to open up. It’s a synchronized dance that happens thousands of times a day without you ever having to think about it. If you're experiencing persistent hoarseness or a feeling that something is "stuck," skip the Google images and see a specialist who can use a scope to see the real thing in real-time.

Next Steps for Better Throat Health:

- Audit your "swallow safety": If you frequently "inhale" your water or find yourself coughing mid-meal, try the "chin-tuck" method to see if it improves the mechanical seal of your epiglottis.

- Monitor Reflux: If you experience frequent heartburn, track your triggers (like caffeine or spicy foods) to prevent long-term irritation of the esophageal lining.

- Check your neck: Familiarize yourself with the feel of your tracheal rings; being aware of your "normal" can help you spot unusual swelling or lumps early.