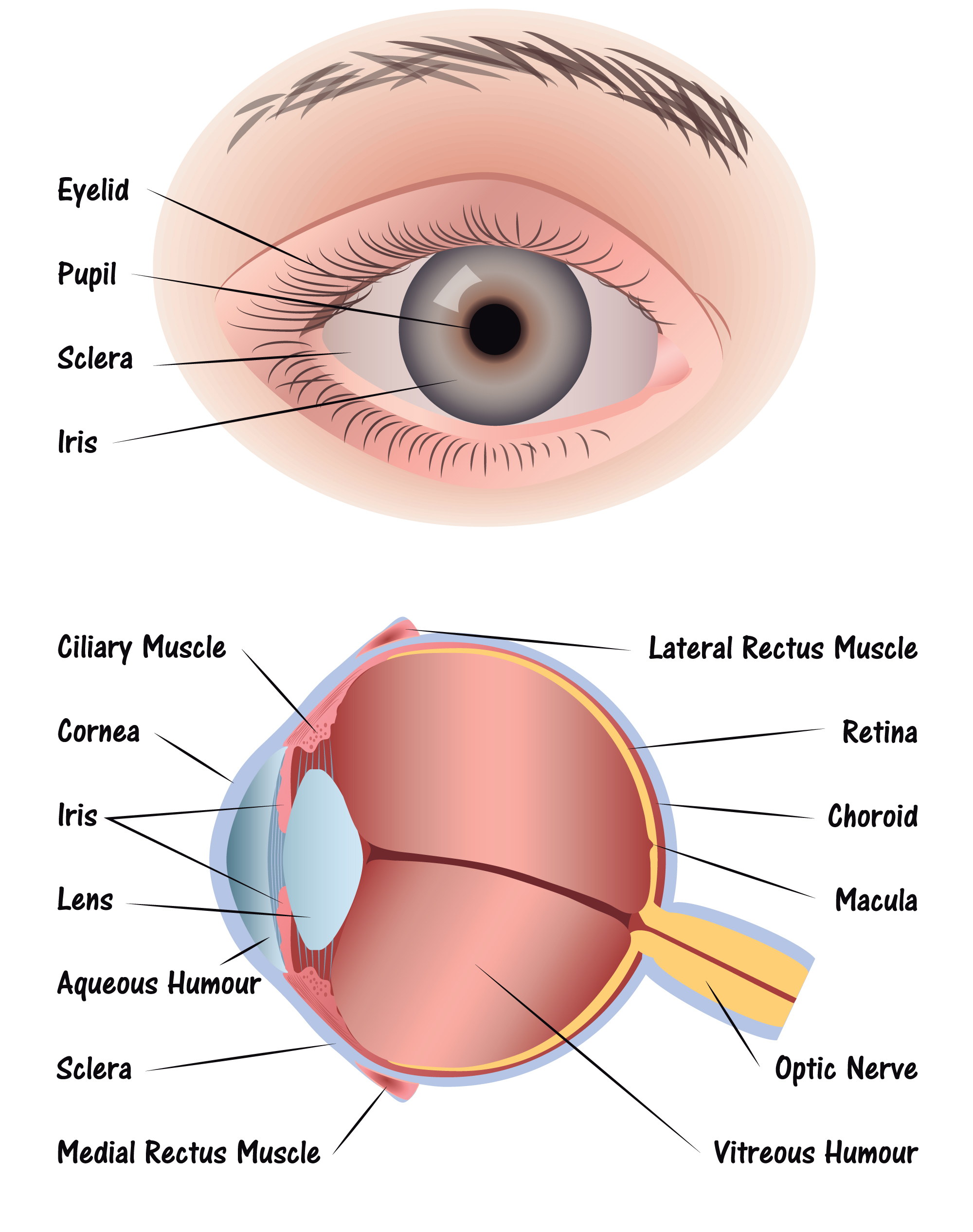

You’ve seen it a thousand times in a doctor’s office or a high school biology textbook. A glossy picture of an eye with labels showing the "big players" like the pupil, the iris, and maybe the cornea if the diagram is feeling fancy. It looks simple. Almost too simple. Most of us glance at those diagrams and think we get it, but honestly, the human eye is a chaotic masterpiece of evolutionary engineering that a static image barely captures.

Eyes aren’t just cameras. They’re extensions of the brain. When you look at a picture of an eye with labels, you're seeing the hardware, but the software—the way the retina processes light into electrochemical signals—is where the real magic happens. It’s wild to think that what we "see" is actually a construction of the brain, not a direct live stream.

The Parts Everyone Forgets to Label

Most diagrams stick to the surface level. You get the iris (the colored part) and the pupil (the hole in the middle). But have you ever noticed those tiny little fibers mentioned in more detailed anatomical studies? Those are the ciliary bodies and zonules of Zinn.

They’re basically the suspension cables of the eye. Without them, your lens wouldn't change shape. You wouldn't be able to switch from looking at your phone to looking at a bird across the street. It’s a mechanical process called accommodation. If you’re looking at a picture of an eye with labels and it doesn't mention the ciliary muscles, you're missing the engine room.

Then there’s the vitreous humor. It’s the clear, jelly-like substance that fills the space between the lens and the retina. People often ignore it because it's just "filler," but it’s what gives the eye its shape. If that pressure drops, the whole system collapses.

Why the Macula Matters More Than the Rest

If you zoom in on a professional picture of an eye with labels, you’ll see a tiny spot on the retina called the macula. This is the VIP section of your vision.

The macula is responsible for your central, high-resolution vision. It’s what you’re using to read these words right now. The rest of your retina handles peripheral vision, which is great for detecting motion (like a car approaching from the side) but terrible for detail. This is why conditions like age-related macular degeneration (AMD) are so devastating—the "labels" on the map are still there, but the most important sensor is broken.

Light’s Weird Journey: A Step-by-Step Breakdown

Let's trace how a photon actually moves through these labeled parts. It’s not a straight line.

🔗 Read more: Images of the Mitochondria: Why Most Diagrams are Kinda Wrong

The Cornea: This is the clear front window. It does most of the focusing work—way more than the lens does, actually. It’s incredibly sensitive. If you’ve ever had a corneal scratch, you know it’s one of the most painful things imaginable because it’s packed with nerve endings.

The Aqueous Humor: This is a watery fluid behind the cornea. It provides nutrients and maintains pressure. If the drainage here gets backed up, you get glaucoma. This is a major reason why eye doctors puff that annoying air into your eye; they're checking the "tire pressure" of this fluid.

The Pupil and Iris: The iris is a muscle. It’s the only internal muscle we can see from the outside without surgery. It expands and contracts to let in just the right amount of light.

The Lens: Think of this as the fine-tuner. While the cornea does the heavy lifting, the lens adjusts to make sure the light hits the retina perfectly. As we get older, this lens gets stiff—that’s why people over 40 suddenly need reading glasses. The lens literally loses its "bounce."

The Retina: This is the "film" in the camera. It’s a layer of light-sensitive cells. Most people know about rods and cones. Rods help you see in the dark (but only in black and white), while cones handle color and detail.

The Blind Spot You Didn't Know You Had

In every picture of an eye with labels, there is a point called the optic disc. This is where the optic nerve exits the eye to go to the brain.

Because there are no photoreceptors here, you are literally blind in that one specific spot. Your brain is a master of deception, though; it "photoshops" the image by using information from the other eye and surrounding details to fill in the gap. You never notice it unless you do one of those specific optical illusion tests. It's a reminder that even the best "labels" don't show the full complexity of how we perceive reality.

💡 You might also like: How to Hit Rear Delts with Dumbbells: Why Your Back Is Stealing the Gains

Common Misconceptions in Visual Diagrams

Honestly, a lot of the diagrams we see are kind of misleading. For instance, the eye is often drawn as a perfect sphere. It’s not. Most eyes are slightly elongated or squashed.

If your eye is a bit too long, the light focuses in front of the retina. Boom: Myopia (nearsightedness). If it’s too short, the light focuses "behind" it, which we call Hyperopia (farsightedness). A picture of an eye with labels usually shows a "perfect" eye, which only about 30% of the population actually has.

Another thing? The "red-eye" effect in old photos. That’s not a camera glitch; it’s a biological fact. You’re seeing a reflection of the choroid, a layer of blood vessels behind the retina. If a diagram doesn't show the choroid, it’s skipping the plumbing that keeps the eye alive.

The Role of the Optic Chiasm

Most diagrams stop at the optic nerve. But the nerve doesn't just go straight back like a wire. It hits the optic chiasm, where the nerves from both eyes cross over. This allows the left side of your brain to process the right side of your visual field, and vice-versa. It’s a weird, "X-shaped" intersection that is crucial for depth perception. Without this crossover, you wouldn't be able to catch a ball or judge how far away a curb is.

How to Use This Knowledge for Better Eye Health

Understanding a picture of an eye with labels isn't just for passing a biology test. It’s about knowing what to tell your doctor.

If you see "floaters" (those little squiggly lines), you’re actually seeing shadows cast on your retina by tiny clumps of protein in your vitreous humor. Usually, it's normal aging. But if you suddenly see a "curtain" falling over your vision, that’s a sign the retina itself is peeling away (retinal detachment). Knowing the labels helps you describe these emergencies.

- Protect the Cornea: Wear sunglasses. UV light can cause "sunburn" on the cornea (photokeratitis) or lead to cataracts (clouding of the lens).

- Rest the Ciliary Muscles: Use the 20-20-20 rule. Every 20 minutes, look at something 20 feet away for 20 seconds. This lets those tiny "suspension cables" relax.

- Check the Retina: Regular dilated exams allow doctors to look through the pupil and see the actual blood vessels of the choroid and the health of the optic nerve. It’s one of the only places in the body where a doctor can see your veins and nerves without cutting you open.

The Future of "Labeling" the Eye

We’re getting into some sci-fi territory now. Bionic eyes and retinal implants are becoming a reality. In these cases, the "labels" change. We start talking about electrode arrays and external processors. Companies like Second Sight have already worked on "Argus II," which bypasses damaged photoreceptors to send signals directly to the optic nerve.

📖 Related: How to get over a sore throat fast: What actually works when your neck feels like glass

When you look at a picture of an eye with labels in 20 years, it might include a port for a computer chip. That sounds crazy, but so did LASIK surgery thirty years ago.

Actionable Insights for Everyday Vision

Instead of just looking at a diagram, take these steps to ensure your "labeled parts" stay functional for as long as possible.

First, get a baseline exam. Even if you think you see fine, conditions like glaucoma have zero symptoms in the early stages because they affect peripheral vision first. Your brain fills in the gaps, so you don't even know you're losing sight until it's too late.

Second, optimize your environment. Blue light is a hot topic, but the real villain is often dry eye and lack of blinking. When we stare at screens, our blink rate drops by about 60%. This dries out the tear film, which is the very first "label" light hits. A dry eye is a blurry eye. Use artificial tears if you work at a computer all day.

Third, eat for your macula. Lutein and zeaxanthin are antioxidants found in leafy greens like kale and spinach. They literally act as internal sunglasses for your retina, filtering out harmful high-energy light.

Finally, understand your prescription. If you have a copy of your eye script, look at the "OS" and "OD" labels. Oculus Sinister (left eye) and Oculus Dexter (right eye). The numbers represent the "diopters" or the power needed to bend light so it hits your retina perfectly. Knowledge of the anatomy makes those random numbers on a piece of paper actually mean something.

Vision is our dominant sense. We dedicate more of our brain to processing sight than any other task. Taking five minutes to really understand a picture of an eye with labels isn't just an academic exercise—it's a maintenance manual for how you experience the world.

To maintain your eye health, schedule a comprehensive dilated eye exam annually, especially if you have a family history of vision issues. Practice the 20-20-20 rule daily to reduce digital eye strain and ensure your workspace has proper lighting to minimize glare on the cornea.