You’ve probably tried it. You’re standing outside, the sky is a deep, bruised purple at sunset, and the sun is this massive, glowing orange coin. You pull out your phone, snap a photo, and... it’s a mess. Instead of that majestic orb, you get a tiny, overexposed white dot or a weird green lens flare that looks like a UFO. It’s frustrating. Honestly, it’s one of the biggest gaps between human perception and digital sensors. Getting an actual picture of a real sun that captures its violent, roiling detail is one of the hardest things to do in photography.

It’s a literal star. We forget that. We’re trying to point a piece of silicon and glass at a 15-million-degree nuclear furnace located 93 million miles away.

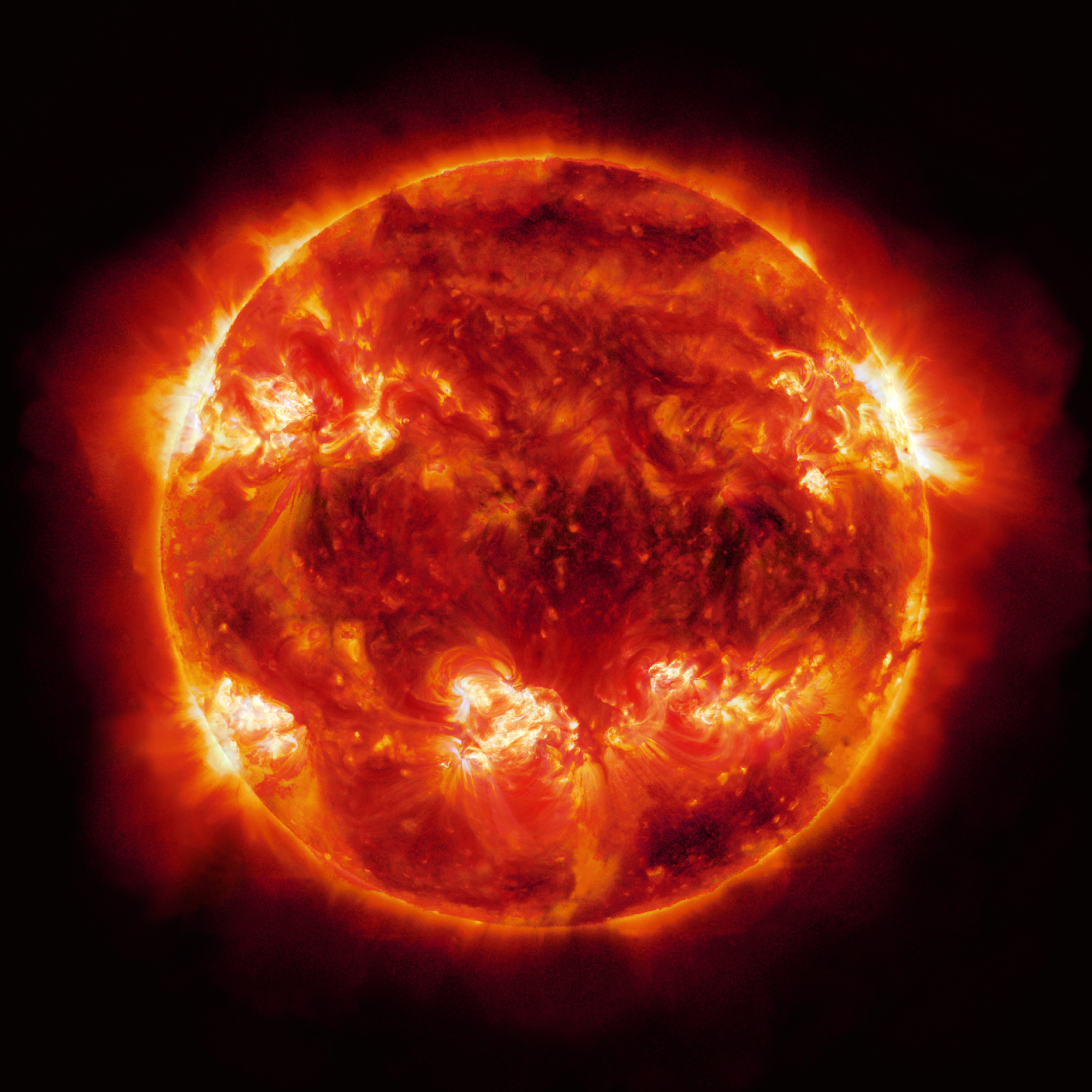

The sun is bright. Really bright. In technical terms, we’re talking about an object that is roughly 1.6 billion nits (a measure of luminance). For context, your high-end smartphone screen might hit 2,000 nits on a good day. When you point a camera at the sun, you’re basically screaming at the sensor. It’s too much information. Most cameras just give up and "clip" the whites, turning the sun into a featureless blob. But when you see those incredible images from NASA or high-end solar astrophotographers, you’re seeing something else entirely. Those aren't "snapshots." They are data visualizations of a magnetic nightmare.

The Problem With Visible Light

If you look at the sun through a standard camera lens without a filter, you’re going to damage your equipment. Or your eyes. Don't do that. Even with a heavy Neutral Density (ND) filter—basically sunglasses for your camera—the sun usually just looks like a white or slightly yellow circle. It’s boring.

Why?

Because the sun’s "surface," the photosphere, is so overwhelmingly bright that it washes out the cool stuff. The solar flares, the loops of plasma, the sunspots—they get buried. To see the "real" sun, experts use something called a Hydrogen-alpha (H-alpha) filter. These filters are incredibly narrow. They block out every single wavelength of light except for a tiny sliver at 656.28 nanometers. This is the wavelength where hydrogen atoms are doing their thing.

✨ Don't miss: Why the Amazon Kindle HDX Fire Still Has a Cult Following Today

When you look through an H-alpha filter, the sun transforms. It’s no longer a smooth ball. It looks like a fuzzy peach, covered in texture called spicules. You see "filaments," which are long, dark ribbons of plasma held up by magnetic fields. It’s gorgeous. It’s also expensive. A decent H-alpha solar telescope can easily cost you $1,000 to $5,000.

Why the color is always "wrong"

Here’s a secret: every picture of a real sun you’ve seen that looks deep red or bright green is technically a lie. Or at least, a stylistic choice. Space is dark, and the sun emits light across the entire spectrum. It’s actually white. If you were in the International Space Station, the sun would look like a pure white ball of light.

The yellow/orange tint we see on Earth is just our atmosphere scattering blue light away. When NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO) takes a photo, they use different wavelengths to see different temperatures of gas. They then color-code them so humans can tell the difference.

- 304 Angstroms (extreme ultraviolet) is usually colored red.

- 171 Angstroms is colored gold to show the corona.

- 94 Angstroms might be colored green to highlight solar flares.

So, when you see a "real" photo, you're looking at a composite. It’s a map of heat and magnetism more than a "snapshot" in the traditional sense.

Solar Maximum and the 2024-2026 Surge

If you’ve noticed more people posting a picture of a real sun lately, there’s a scientific reason for it. The sun goes through 11-year cycles. Right now, we are at or near the "Solar Maximum." This is the peak of solar activity.

🔗 Read more: Live Weather Map of the World: Why Your Local App Is Often Lying to You

During this phase, the sun's magnetic poles literally flip. It’s chaotic. This chaos creates more sunspots—cool regions where magnetic lines have become so tangled they choke off the flow of heat. It also creates more Coronal Mass Ejections (CMEs). These are the massive clouds of plasma that hit Earth’s atmosphere and create the Northern Lights.

In May 2024, we had the strongest solar storm in over two decades. People in Florida were seeing auroras. Because of this, everyone with a DSLR and a solar filter has been pointing their gear upward. We are seeing more detail in solar photography now than at any point in human history, partly because sensor technology has finally caught up to the Sun's dynamic range.

How the pros do it (Lucky Imaging)

You can't just take a long exposure of the sun. The Earth’s atmosphere is "boiling." Heat rising from the ground makes the air shimmer, which blurs the image.

To get around this, astrophotographers use a technique called "Lucky Imaging."

- They record a high-speed video of the sun, taking thousands of frames per minute.

- They use software like AutoStakkert! to analyze every single frame.

- The software picks the 1% of frames where the atmosphere happened to be still for a fraction of a second.

- It stacks those "lucky" frames on top of each other to cancel out noise and bring out the crisp edges of sunspots.

It’s tedious. It takes hours of processing. But the result is a picture of a real sun that looks like you’re hovering just a few thousand miles above it. You can see the "granulation"—cells of plasma the size of Texas bubbling up to the surface. It looks like a pot of boiling oatmeal, if oatmeal were 10,000 degrees Fahrenheit.

💡 You might also like: When Were Clocks First Invented: What Most People Get Wrong About Time

Common Misconceptions About Solar Photos

People often think sunspots are "burnt" parts of the sun. They aren't. They’re actually still incredibly bright and hot (around 3,500 degrees Celsius). They only look black because the rest of the sun is so much hotter (5,500 degrees Celsius) and brighter. If you could pull a sunspot out and put it in the night sky, it would shine brighter than the full moon. It’s all about contrast.

Another big one? The "size" of the sun in photos. Most people use wide-angle lenses on their phones. This makes the sun look like a tiny dot. To get a real, impactful picture of a real sun, you need focal lengths that would make a paparazzi jealous. We're talking 400mm, 600mm, or even 2000mm through a telescope. At that magnification, you can actually see the curvature of the star.

Taking Your Own Solar Photos: A Practical Reality Check

If you want to try this, don't just wing it. You can literally melt the internals of your phone or camera.

- Solar Filters are Non-Negotiable: You need a "White Light" filter at the very least. This is a sheet of polymer or glass that blocks 99.999% of sunlight. It makes the sun look like a white or slightly yellow disk. You’ll see sunspots, but you won't see those cool "loops" of fire.

- The Eclipse Effect: Most people only care about a picture of a real sun during an eclipse. During totality, you can actually take photos without a filter. That’s the only time you can see the Corona—the sun’s outer atmosphere—with the naked eye. It looks like ghostly white petals stretching out into space.

- Focusing is a Nightmare: Your camera's autofocus will hate the sun. You have to switch to manual and use "Live View" to zoom in on a sunspot or the edge of the sun to get it sharp.

What to Look for in a "Real" Image

When you’re browsing images from the Parker Solar Probe or the Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope, look for the details.

Look for the "light bridges" crossing over sunspots.

Look for the "penumbra"—the feathery fringe around the dark center of a spot.

These aren't just pretty patterns; they are visual representations of physics at a scale we can't really comprehend.

The Sun is a dynamic, changing object. It rotates. It pulses. A photo taken today will look completely different from one taken next week. That’s why scientists are so obsessed with it. We’re living next to a laboratory that is constantly performing experiments in plasma physics, and every picture of a real sun is a snapshot of that data.

Actionable Steps for Better Solar Viewing

If you're interested in seeing the sun more clearly without spending thousands, there are a few "pro" moves you can make.

- Check the Space Weather: Use sites like SpaceWeather.com or the SDO website. They show real-time images of the sun. If you see a massive sunspot group (like AR3664, which caused the big May 2024 storm), that’s the time to get your gear out.

- Solar Projection: If you don't have a filter, you can project the sun's image through a pair of binoculars onto a white piece of paper. Never look through the binoculars. Just hold the paper behind them. It’s a safe, "analog" way to see sunspots.

- Use Specialized Apps: Apps like "Solar Monitor" can tell you exactly what’s happening on the solar disk right now, including where flares are popping off.

- Invest in Solar Film: You can buy sheets of Baader AstroSolar film for about $30. You can cut it and tape it over your camera lens (make sure there are no holes!). This is the cheapest way to get a high-quality, safe picture of a real sun.

The sun is the only star we can see in detail. Every other star in the sky is just a point of light, even through the biggest telescopes. Capturing the sun is our only way to witness the mechanics of the universe up close. It takes patience, the right safety gear, and an understanding that what we see with our eyes is only a tiny fraction of the "real" star.