If you’ve ever stumbled across a picture of a liver with cirrhosis, your first instinct was probably a mix of "gross" and "how?" It doesn’t look like the smooth, dark-maroon organ you see in high school biology textbooks. Honestly, it looks like something that was left in a dehydrator for too long or maybe a piece of ginger root that’s seen better days.

It's bumpy. It's lumpy. It's yellow-ish.

But those bumps—what doctors call regenerative nodules—tell a story about a body trying desperately to save itself. Most people assume cirrhosis is just "the alcohol disease," but that's a massive oversimplification that hurts patients. You can get here through fatty liver disease, hepatitis, or even autoimmune issues. The image of the liver is just the final receipt of years of quiet, invisible struggle.

What You Are Actually Seeing in a Picture of a Liver with Cirrhosis

When you look at a healthy liver, it’s remarkably uniform. It’s the largest internal organ and, frankly, one of the hardest working. But when it’s under constant attack—whether from toxins or a virus—it develops scar tissue.

Think of it like this.

If you cut your skin, you get a scar. That scar isn’t the same as your original skin; it’s tougher, less flexible, and doesn't have sweat glands. Now, imagine that happening inside your liver, over and over again, for a decade. Eventually, the scar tissue (fibrosis) starts to outnumber the healthy cells (hepatocytes).

The "Cobblestone" Texture

In a picture of a liver with cirrhosis, the most striking feature is the texture. It looks like a cobblestone street. These bumps happen because the healthy parts of the liver are trying to grow back. They are literally "regenerating." However, because they are surrounded by thick bands of scar tissue, they can't expand smoothly. They get squeezed into these tight, rounded nodules.

The color is usually off, too. A healthy liver is deep red because it’s full of blood. A cirrhotic liver often looks tan or yellow. This is frequently due to steatosis (fatty deposits) or bile being trapped because the plumbing inside the organ is totally blocked by scars.

👉 See also: Cleveland clinic abu dhabi photos: Why This Hospital Looks More Like a Museum

Why the Anatomy Changes So Drastically

The liver is incredibly resilient. You can cut away a huge chunk of it, and it will grow back. But it has a breaking point. When the inflammation never stops, the "bridge" between different parts of the liver gets replaced by collagen.

This isn't just an aesthetic problem.

As the liver shrinks and hardens, blood can’t flow through it easily. Imagine trying to push water through a sponge that has been dipped in concrete and allowed to dry. The pressure builds up. This leads to portal hypertension, which is why people with advanced liver disease get those terrifying swollen veins in their esophagus or a belly full of fluid.

Dr. Anna Lok, a renowned hepatologist at the University of Michigan, has spent years documenting how these structural changes correlate with patient outcomes. The more "bridge" scarring you see in a biopsy or a picture of a liver with cirrhosis, the higher the risk for liver failure. It's a direct 1:1 relationship between the physical wreckage and the loss of function.

Common Misconceptions About These Images

Most people see a "drinker's liver" and think they know the whole story.

They don't.

Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD)—now often called MASLD—is becoming a leading cause of cirrhosis in the United States. You could be a lifelong teetotaler and still end up with a liver that looks exactly like the one in the textbook photos. Genetics play a huge role. Metabolic syndrome plays a huge role.

✨ Don't miss: Baldwin Building Rochester Minnesota: What Most People Get Wrong

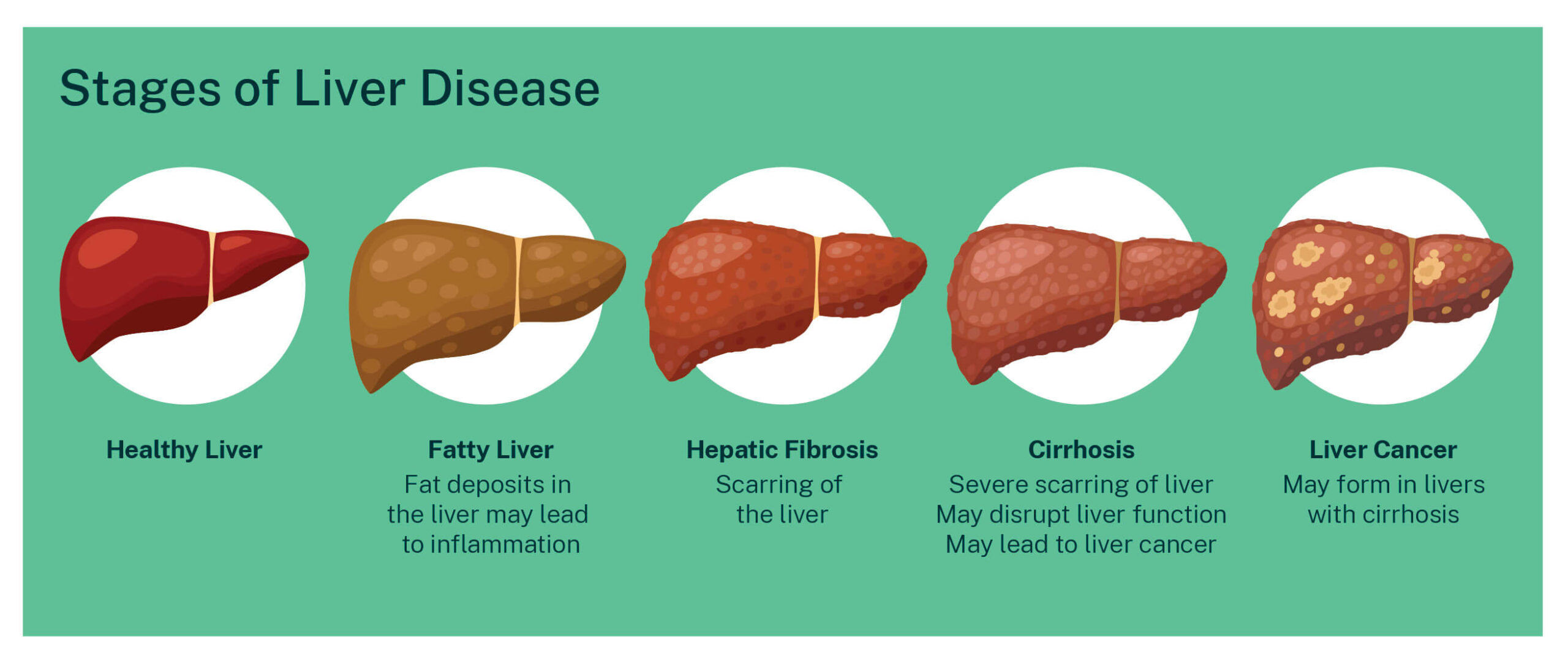

Also, a liver doesn't go from "perfect" to "cirrhotic" overnight. It’s a slow burn. There are stages:

- Inflammation: The liver gets swollen.

- Fibrosis: Thin strands of scar tissue appear.

- Cirrhosis: The "cobblestone" appearance becomes permanent.

By the time you can actually see the damage in a picture of a liver with cirrhosis, the organ is usually in "compensated" or "decompensated" status. In the compensated phase, the liver is scarred but still doing its job. You might not even feel sick. That’s the scary part. You’re walking around with a lumpy, scarred organ and feel totally fine until one day, you aren't.

How Doctors Identify Cirrhosis Without Surgery

Back in the day, the only way to really "see" the liver was to cut someone open or do a blind needle biopsy. Both are, understandably, not fun.

Nowadays, we have FibroScan.

It’s basically a high-tech ultrasound that measures "stiffness." It sends a pulse through your side and measures how fast it travels. Since scar tissue is stiffer than healthy tissue, the machine can give a pretty accurate "score" of how much scarring is there. It’s like a digital version of looking at a picture of a liver with cirrhosis.

MRI elastography is another one. It creates a color-coded map of the liver's density. In these scans, a healthy liver might look blue or purple (soft), while a cirrhotic one shows up as bright red or orange (hard). It’s a literal heat map of the damage.

Can You "Fix" a Liver That Looks Like That?

This is where the nuance comes in. For a long time, the medical consensus was that once a liver looks like a lumpy rock, you're done. The only "cure" was a transplant.

🔗 Read more: How to Use Kegel Balls: What Most People Get Wrong About Pelvic Floor Training

We now know that isn't strictly true.

If you catch it early enough and stop the cause—whether that’s quitting alcohol, clearing a Hepatitis C infection with antivirals, or losing significant weight—the liver can actually heal some of that scarring. It might never look "brand new" again, but the nodules can shrink, and the stiffness can decrease.

However, there is a "point of no return." Once the architecture of the liver is completely warped, the risk of liver cancer (Hepatocellular Carcinoma) skyrockets. The body’s attempt to regenerate cells in those nodules is messy, and messy cell growth is exactly how cancer starts.

Reality Check: What the Image Doesn't Show

A picture of a liver with cirrhosis is a snapshot of a moment. It doesn't show the fatigue. It doesn't show the "brain fog" caused by toxins building up in the blood. It doesn't show the intense itching or the jaundice.

It’s just the physical manifestation of a systemic failure.

If you are looking at these images because you’re worried about your own health, remember that the liver is remarkably forgiving if you give it a chance. Seeing the damage is often the wake-up call people need.

Actionable Next Steps for Liver Health

- Get a FibroScan: If you have risk factors like Type 2 diabetes, high cholesterol, or a history of heavy drinking, ask your doctor for a non-invasive stiffness test. Blood tests (like ALT and AST) don't always tell the whole story.

- Check Your Meds: Over-the-counter stuff like Tylenol (acetaminophen) is processed by the liver. If your liver is already struggling, even "normal" doses can be dangerous.

- Screen for Viral Hepatitis: Hep B and C can stay silent for decades. A simple blood test can tell you if a virus is slowly scarring your liver behind your back.

- Focus on Mediterranean Eating: It sounds cliché, but the Mediterranean diet is the most well-studied eating pattern for reducing liver fat and preventing the progression to cirrhosis.

- Watch the Fructose: High-fructose corn syrup is particularly hard on the liver. It's one of the fastest ways to build up the fat that eventually leads to those lumpy nodules.

The transition from a healthy organ to a picture of a liver with cirrhosis represents a long journey of damage. Understanding that the "bumps" are actually the body's failed attempt at healing can change how you view the condition—from a scary medical image to a clear signal that the body needs an intervention before the scarring becomes irreversible.