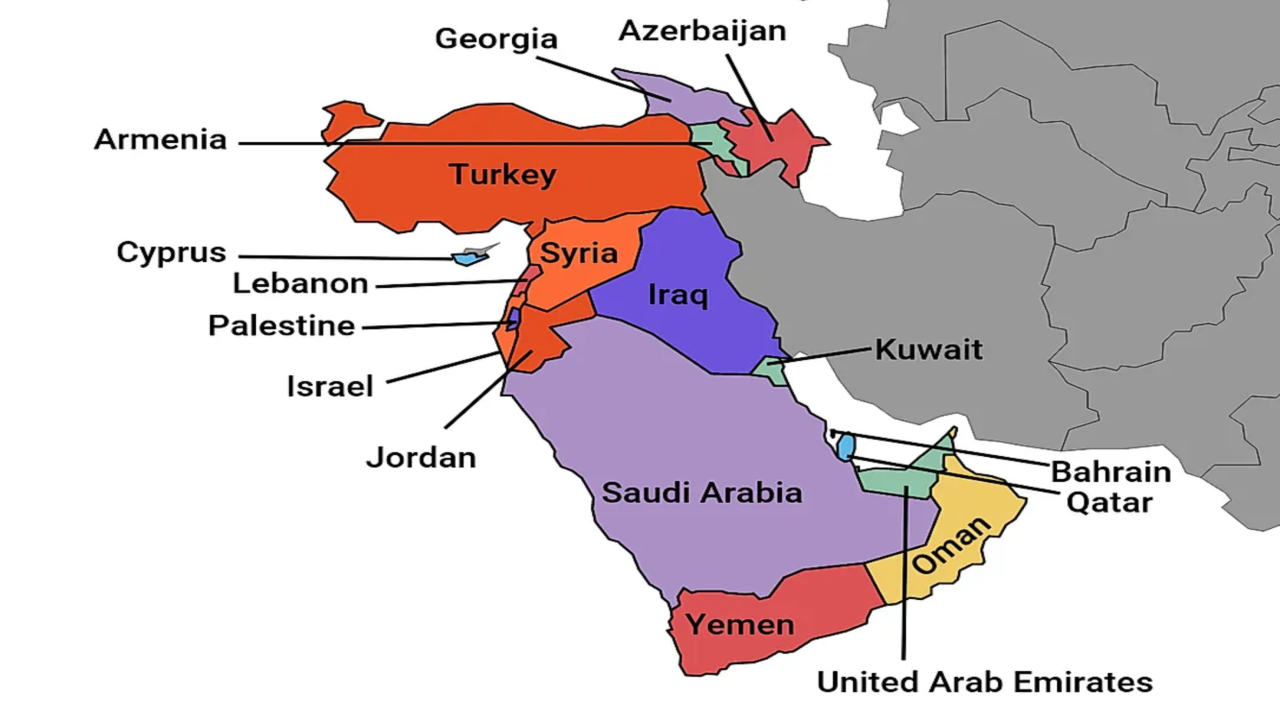

If you look at a physical southwest asia map, you’ll notice something immediately. It is brown. Deep, rugged, unforgiving brown. Most people call this region the Middle East, but that’s a political term. When we talk about the physical geography, we are looking at a massive tectonic collision zone that dictates where people live, where they fight, and where the world’s energy flows. It’s not just a flat piece of paper. It is a high-stakes puzzle of plateaus and bottlenecks.

Honestly, the map looks like a car crash of tectonic plates. You have the Arabian Plate pushing north into the Eurasian Plate. This isn't just a geology fact you’d find in a textbook; it’s the reason why Tehran is prone to earthquakes and why the Zagros Mountains are so incredibly difficult to cross. Geography is destiny here.

Most travelers or students looking at a physical southwest asia map for the first time are surprised by how little "green" there actually is. We hear about the "Fertile Crescent," but on a modern satellite view, that greenery is a thin, fragile sliver compared to the vastness of the Rub' al Khali or the Iranian Plateau.

The High Ground: Why the Plateaus Matter

The Anatolian Plateau in Turkey and the Iranian Plateau are the two "towers" of Southwest Asia. They sit high above the surrounding plains. This elevation creates a natural fortress. Throughout history, empires based on these plateaus—like the Byzantines or the Persians—used the height to defend against invaders from the lowlands.

If you're looking at the physical southwest asia map, zoom in on the Zagros Mountains. They run for about 1,500 kilometers. They aren't just hills; they are jagged, folded limestone ridges that act as a massive wall between the Mesopotamian plains of Iraq and the interior of Iran. This is why the Iran-Iraq war in the 1980s became such a bloody stalemate. The geography simply wouldn't allow for easy movement. Tanks don't do well on 40-degree inclines.

Then there’s the Hindu Kush in the far east of the region. This is where the world gets vertical. These mountains are an extension of the Himalayas. They are the reason why Afghanistan is often called the "Graveyard of Empires." It’s not necessarily the people; it’s the terrain. You can’t conquer a country when every valley is a self-contained world separated by 15,000-foot peaks.

Water: The Only Currency That Actually Counts

Oil gets the headlines. Water keeps people alive. When you examine a physical southwest asia map, look for the blue lines. They are rare. The Tigris and the Euphrates are the most famous, starting in the mountains of Turkey and flowing down through Syria and Iraq.

🔗 Read more: Why Showboat Saloon Wisconsin Dells is Still the Best Spot for a Cold Beer and Live Music

But here is the catch. Turkey sits upstream. Because Turkey controls the headwaters in the Taurus Mountains, they have the power to literally turn off the tap for downstream neighbors. This is the Southeastern Anatolia Project (GAP). It’s a series of 22 dams. When Turkey fills a reservoir, the water level in Baghdad drops. It’s a silent, geographical weapon.

- The Jordan River: It’s tiny. You could practically jump across it in some places. Yet, it is the primary water source for Israel, Jordan, and the Palestinian territories.

- The Orontes: Flows north, which is weird, but it feeds the heart of Syria.

- Qanats: In Iran, they don't even use surface water in many places. They use ancient underground tunnels to bring water from the mountains to the desert.

Mountains capture the moisture. Without the heights of the Caucasus or the Alborz, this entire region would be a scorched, uninhabitable dust bowl. The mountains act like water towers, storing snow and releasing it slowly through the spring.

The Bottlenecks and Gateways

Geography creates "choke points." If you want to understand why the US Navy is always in the Persian Gulf, look at the Strait of Hormuz on your physical southwest asia map. At its narrowest, the shipping lane is only about two miles wide. Twenty percent of the world's oil passes through that tiny gap.

It's terrifyingly narrow. If a couple of tankers sank there, the global economy would basically stop.

Then you have the Bab el-Mandeb, the "Gate of Tears," down by Yemen. It connects the Red Sea to the Indian Ocean. It’s another narrow corridor that makes the Suez Canal relevant. Without these physical gaps in the landmass, the world’s trade routes would have to go all the way around Africa. Geography saves us thousands of miles, but it also creates targets for piracy and geopolitical posturing.

The Empty Quarter: A Sea of Sand

The Rub' al Khali, or the Empty Quarter, dominates the southern part of the Arabian Peninsula. It’s the largest contiguous sand desert in the world. It’s roughly the size of France.

Most maps show it as a yellow void. But it’s not empty. It’s a shifting, moving landscape of dunes that can reach 800 feet in height. For centuries, this was a barrier as effective as any ocean. Bedouin tribes managed to navigate it, but for any organized army, it was a death trap. Today, we know it sits on top of some of the largest oil reserves on the planet, like the Ghawar Field. The contrast is wild: the most "worthless" looking land on the surface is the most valuable underneath.

Why Dead Sea Geography is Bizarre

The lowest point on Earth is right here. The Dead Sea sits at about 1,412 feet below sea level. It’s part of the Great Rift Valley, a massive crack in the Earth’s crust that pulls away towards Africa.

The air is thicker there. You can’t sink in the water because the salt concentration is so high—about 34%. But the physical southwest asia map shows a tragedy here, too. The Dead Sea is shrinking. Because humans are diverting the water from the Jordan River for farming, the sea is receding by about three feet every year. Huge sinkholes are opening up along the coast, swallowing buildings and roads. It’s a physical reminder that geography isn't static; it's reacting to us.

The Mediterranean Fringe vs. The Interior

The Levantine coast—Lebanon, Israel, western Syria—is the Mediterranean exception. It’s green. It’s humid. It has cedar forests. This is because the coastal mountains (like the Lebanon Mountains) trap the moisture coming off the sea.

Once you cross those mountains, the rain shadow effect kicks in immediately. You can drive 30 miles inland and go from a lush forest to a parched desert. This sharp divide is why populations are so concentrated along the coast. The interior is a place of nomadic movement, while the coast is a place of settled cities and ancient ports like Byblos and Tyre.

Actionable Insights for Using a Physical Map

To truly understand Southwest Asia through its physical geography, don't just look at the borders. Borders are often fake, drawn by colonial powers in the 20th century. Instead, follow these steps:

- Trace the 1,000-meter contour line. Anyone living above this line has a completely different lifestyle, climate, and security outlook than those below it.

- Identify the "Wadis." These are dry riverbeds that flash flood during rare rains. In desert warfare and travel, these are both highways and death traps.

- Locate the Alluvial Fans. At the base of the mountains in Iran and Oman, look for the fan-shaped sediment deposits. This is where the best soil is. This is where the cities are.

- Check the Dust Corridors. Use satellite layers to see how wind moves through the "Sistan" region. The "Wind of 120 Days" in eastern Iran can reach 100 mph, shaping the very land and making permanent settlement nearly impossible.

When you master the physical southwest asia map, you stop seeing a collection of warring states and start seeing a complex organism of mountains, basins, and vital water veins. It's the ultimate cheat code for understanding world news. You realize that people aren't just fighting over religion or politics—they are often fighting over the few pieces of land that the geography actually made livable.