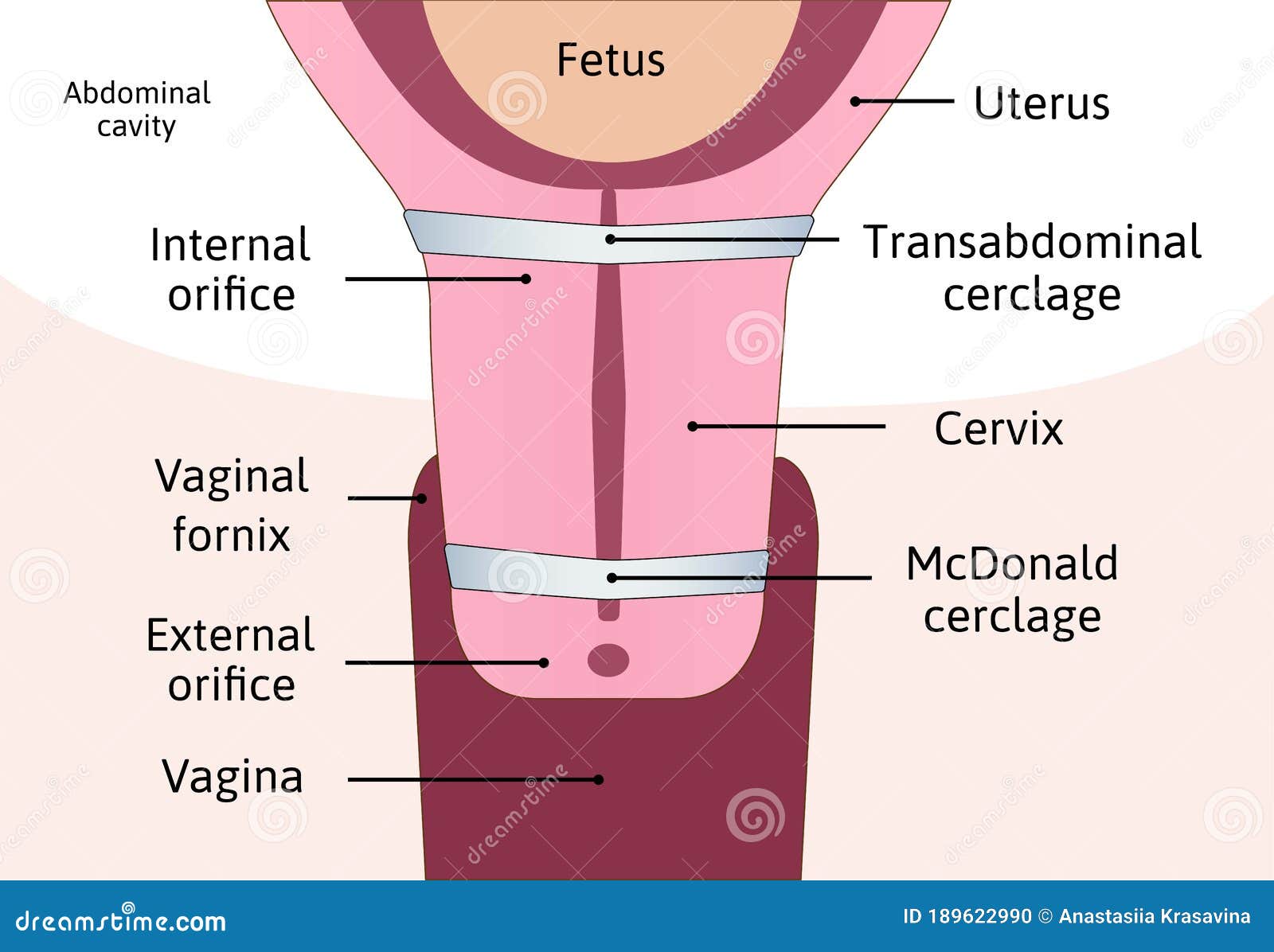

Ever stared at those clinical diagrams in a doctor's office? You know the ones. They look like a perfectly symmetrical, pinkish-beige butterfly. Everything is neat. Everything is labeled with crisp black lines. But honestly, if you ever saw a real photo of uterus and cervix anatomy from an actual surgical suite or a colposcopy, you’d realize those drawings are basically the "Instagram filter" version of human biology. Real bodies are messy. They are asymmetrical. They have textures that no textbook illustrator can quite capture without making it look, well, a bit gross to the uninitiated.

Understanding what’s actually going on inside is more than just a biology lesson. It’s about knowing what "normal" looks like so you don't panic when you see your own results or look at a monitor during an exam.

The Cervix: It’s Not Just a Hole

Most people think of the cervix as a simple gateway. A door that stays shut until a baby needs to come out. In a real-life photo of uterus and cervix structures, the cervix looks more like a small, firm, circular "doughnut" of tissue. It's usually a pale pink, but the shade changes. It can be deep red during ovulation or a sort of bluish-purple if someone is pregnant—a phenomenon doctors call Chadwick’s sign.

It’s surprisingly small. We’re talking about the size of a quarter.

When you look at a colposcopy image—which is basically a high-definition, magnified photo of the cervix—you’ll see the "transformation zone." This is the specific area where the skin-like cells of the outer cervix (ectocervix) meet the mucus-producing cells of the inner canal (endocervix). This is where 90% of cervical cancers start. If you’ve ever had an "abnormal" Pap smear, this is the area the doctor was squinting at through the lens.

Why Texture Matters

Texture is everything. A healthy cervix is smooth. If you see a photo of uterus and cervix health that shows "Nabothian cysts," don't freak out. They look like tiny, yellowish or white pimples on the cervix. They aren't dangerous. They are just blocked mucus glands. They’re basically the "skin bumps" of the reproductive system.

🔗 Read more: How Do You Know You Have High Cortisol? The Signs Your Body Is Actually Sending You

But then there's the "strawberry cervix." This is a real medical term (punctate hemorrhages). It happens during a Trichomoniasis infection. The tissue gets covered in tiny red dots, making it look exactly like the surface of a strawberry. It’s fascinating, kinda weird, and a very clear sign that something is wrong.

Looking at the Uterus: The Muscular Powerhouse

If we move past the cervix, we get to the uterus. You won't see this in a standard pelvic exam. To get a real photo of uterus and cervix orientation from the outside, doctors usually use a laparoscope—a tiny camera inserted through the belly button.

The uterus is a beast.

It’s roughly the size and shape of an upside-down pear. In a healthy person who hasn't been pregnant, it’s about 3 inches long. It’s not just sitting there, either. It’s held up by a web of ligaments that look like thick, white guitar strings in a high-res surgical photo.

Fibroids: The Uninvited Guests

If you look at photos of a uterus with fibroids, it doesn't look like a pear anymore. It looks like a lumpy sack of potatoes. Fibroids (leiomyomas) are incredibly common. Dr. Elizabeth Stewart at the Mayo Clinic has noted that by age 50, up to 80% of women have them. They are benign, but they can grow to the size of a grapefruit. Seeing a photo of a fibroid-laden uterus explains why people feel so much pressure and pain. The tissue is literally being stretched out of shape by these hard, dense balls of muscle.

💡 You might also like: High Protein Vegan Breakfasts: Why Most People Fail and How to Actually Get It Right

Misconceptions We Need to Kill

We have to stop pretending everyone's internal anatomy is identical.

- The Tilted Uterus: About 25% of people have a retroverted (tilted) uterus. In a photo, it looks like it’s leaning toward the spine instead of the bladder. It's not a "condition." It’s just a variation, like being left-handed.

- The Shape: Some people are born with a "bicornuate" uterus. It’s shaped like a heart. In a surgical photo of uterus and cervix anatomy, you can see a deep indentation at the top. It looks cool, though it can make pregnancies a bit more complicated.

- Color Variations: Internal tissue isn't a uniform "flesh tone." Depending on where you are in your cycle, the blood flow changes, making the organs look vibrant red or duller pink.

What Real Medical Images Reveal About Endometriosis

Endometriosis is one of the most misunderstood conditions in medicine. You can't see it on a regular ultrasound most of the time. You need a surgical photo of uterus and cervix surroundings to find it.

Surgeons look for "powder burn" lesions. These are small, dark spots—sometimes black, sometimes rust-colored—that look like someone flicked ash onto the pelvic lining. They can also look like clear blisters or "chocolate cysts" on the ovaries. Seeing these images is often the first time a patient feels validated. They aren't "just having a bad period." There is literal, visible evidence of disease that shouldn't be there.

The complexity is wild. Sometimes the uterus can even get "stuck" to the bowel because of scar tissue (adhesions). In a photo, this looks like thin, translucent spiderwebs pulling the organs together.

The Role of Modern Imaging

We’ve moved way beyond grainy black-and-white photos.

📖 Related: Finding the Right Care at Texas Children's Pediatrics Baytown Without the Stress

Hysteroscopy is a big one. This involves putting a camera inside the uterus. The resulting photo of uterus and cervix interior shows the endometrium—the lining that sheds every month. It looks lush, almost like the bottom of the ocean. You can see polyps (which look like small, hanging grapes) or septums (walls of tissue that shouldn't be there).

Then there's the 3D Ultrasound. It’s not a "photo" in the traditional sense, but it reconstructs the organs into a three-dimensional model. It helps doctors see the volume of the muscle and the exact location of any growths.

What You Should Actually Do With This Information

Looking at a photo of uterus and cervix anatomy shouldn't just be a curiosity. It should be a tool for your own health advocacy.

- Ask for the Screen: If you are getting a colposcopy or a hysteroscopy, ask if you can see the monitor. Many doctors are happy to point out what you’re looking at. It takes the mystery—and often the fear—out of the procedure.

- Know Your Terms: If your doctor mentions an "ectropion" (where the inner cells of the cervix grow on the outside), don't panic. It looks bright red and scary in a photo, but it’s often totally normal, especially in people on birth control or those who are pregnant.

- Document Your History: If you have surgery (like for endometriosis or fibroids), ask for the pictures. Surgeons usually take a set of photos during laparoscopy. Keep these in your personal digital health record. If you switch doctors, showing a new surgeon exactly what your pelvic cavity looked like two years ago is infinitely more valuable than just saying "I had some scar tissue."

- Compare, Don't Despair: If you find yourself googling images, remember that the "scary" ones are the ones that get published in medical journals. Most real-life anatomy is unremarkable.

Real health is about visibility. The more we understand that the uterus and cervix aren't just "parts" but dynamic, changing organs with their own textures and quirks, the better we can take care of them. Anatomy isn't a textbook illustration. It's living tissue. And honestly? It’s pretty impressive when you see it for what it actually is.

If you're dealing with pelvic pain, heavy bleeding, or just a weird Pap result, getting a clear visual—whether through a camera or high-res imaging—is usually the first step to actually fixing the problem instead of just guessing. Stop relying on the diagrams. If you can, look at the real data. It's your body, after all.