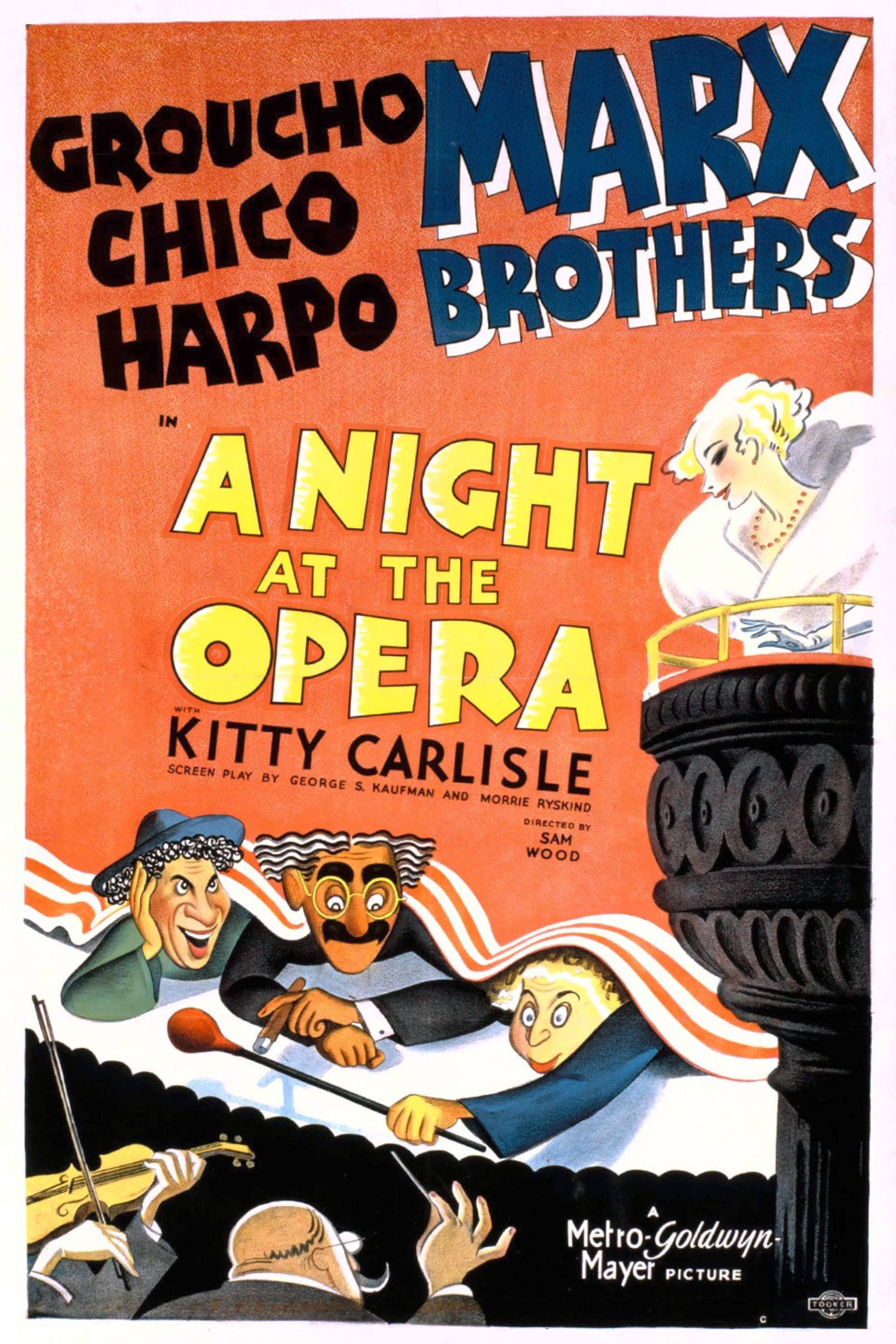

The Marx Brothers were basically washed up in 1934. Paramount had dropped them after Duck Soup tanked at the box office, and Zeppo, the "straight man" brother, had finally quit to become a talent agent. People thought the act was dead. Then came Irving Thalberg. He was the "Boy Wonder" at MGM, and he had a crazy idea: what if we actually gave these guys a plot? That gamble resulted in A Night at the Opera 1935, a film that didn't just save their careers—it redefined what a big-budget comedy could actually look like.

Most people today see old black-and-white clips and think they’re just watching museum pieces. They aren't. If you sit down and watch the stateroom scene today, you’ll probably laugh harder than you did at anything released in the last decade. It’s chaotic. It’s relentless. It’s the kind of timing that you just don't see anymore because it was forged in front of live audiences.

The MGM Makeover: How Thalberg Fixed the Formula

Before A Night at the Opera 1935, Groucho, Chico, and Harpo were essentially human cartoons. They broke the fourth wall constantly. They didn't care about the story. In their Paramount films, they were often antagonists who destroyed everything in sight for no reason other than it was funny. Thalberg changed that. He told them they needed to be "on the side of the angels."

He gave them a reason to be funny. In this film, they are helping two young opera singers, Ricardo and Rosa (played by Allan Jones and Kitty Carlisle), find love and success. By making the brothers the "good guys" who were taking down the pompous, villainous opera stars, Thalberg made the audience actually care if they succeeded. It sounds like a small tweak, but it changed the stakes. Suddenly, the comedy had a heartbeat.

The brothers actually toured the movie's comedy sketches on the vaudeville circuit before filming a single frame. This is a huge detail that most modern viewers miss. They performed the "Stateroom Scene" and the "Contract Scene" in front of live crowds in cities like Salt Lake City and Seattle. If a joke didn't get a laugh, it was cut. If a silence lasted too long, they tightened the timing. By the time they got to the soundstage at MGM, the rhythm was perfect. It was science.

That Ridiculous Stateroom Scene

You know the one. Otis B. Driftwood (Groucho) is in a tiny cabin on a ship. He starts ordering dinner. Two hard-boiled eggs. "Make that three hard-boiled eggs!" Harpo honks a horn. "Make that four hard-boiled eggs!"

It starts with just Groucho and the furniture. Then the trunks come in. Then the stewards. Then the manicurists, the engineers, the girl looking for her aunt. It’s a masterclass in claustrophobic choreography. At one point, there are 15 people crammed into a room that shouldn't fit four. The payoff—where the door finally opens and everyone spills out like a human waterfall—is one of the most iconic images in cinema history.

But here’s the thing: it wasn't just about the bodies in the room. It was the dialogue. Groucho’s rapid-fire delivery as Driftwood is peak Marx. He’s talking to the stewards, talking to the passengers, and insulting everyone under his breath. It’s exhausting to watch in the best way possible. Honestly, most modern comedies struggle to keep that kind of energy for five minutes, let alone an entire sequence.

📖 Related: Isaiah Washington Movies and Shows: Why the Star Still Matters

The Contract Scene: "The Party of the First Part"

If the stateroom scene is the physical peak, the contract scene is the intellectual one. Groucho and Chico tearing apart a legal document is basically a 5-minute roast of bureaucracy.

"The party of the first part shall be known in this contract as the party of the first part."

It’s nonsense. Pure, unadulterated nonsense. But it’s also a biting satire of how people use language to confuse others. When they get to the "Sanity Clause," and Chico famously quips, "You can't fool me, there ain't no Sanity Clause," it’s a pun that has lived for nearly a century.

People forget that Chico Marx was actually a genius at this "immigrant misunderstanding" routine. He played the character of the Italian trickster so well that people often forgot he was a Jewish kid from New York named Leonard. His chemistry with Groucho in A Night at the Opera 1935 is the best it ever was. They were two sides of the same coin: Groucho used words to attack, and Chico used words to confuse.

Why the Musical Numbers Actually Matter

A common complaint about 1930s comedies is that they always stop for these long, "boring" musical interludes. You’ve got Kitty Carlisle and Allan Jones singing "Cosi-Cosa" or "Alone," and modern audiences usually reach for the fast-forward button.

Don't.

In A Night at the Opera 1935, the music serves a purpose. It provides the "relief" from the chaos. More importantly, it gives Harpo and Chico their solo spots. Harpo’s harp solo in this film is genuinely beautiful. He was a self-taught musician who played the "wrong" way—he rested the harp on the wrong shoulder—but his talent was undeniable. When he plays, the movie stops being a screwball comedy and becomes something almost poetic.

👉 See also: Temuera Morrison as Boba Fett: Why Fans Are Still Divided Over the Daimyo of Tatooine

Chico’s piano playing is just as vital. He had this "shooting the keys" technique where he’d use his index finger like a pistol. It was a gimmick, sure, but he was a legitimate player. These moments allowed the audience to breathe. Without them, the frantic pace of the comedy would probably be too much to handle for 90 minutes.

The Climax: Total Opera Anarchy

The final act of the film is a demolition job on high society. The brothers basically infiltrate a performance of Il Trovatore to ruin the career of the villainous tenor Lassparri and get their friend Ricardo on stage.

It’s beautiful destruction.

They switch the sheet music to "Take Me Out to the Ballgame" mid-overture. They swing from the ropes in the rafters, tearing down backdrops so the singers find themselves standing in front of a street scene or a railroad station. Harpo and Chico are literally swinging across the stage like Tarzan.

This was the Marx Brothers' "Statement." They were the counter-culture before that was a term. They were taking the most "sacred" art form of the elite—the Opera—and dragging it into the dirt. And the 1935 audience loved it. Remember, this was the middle of the Great Depression. People didn't want to see rich people in tuxedos acting posh; they wanted to see Harpo Marx hit them with a mallet.

Impact on Pop Culture and Beyond

You can see the DNA of A Night at the Opera 1935 everywhere.

- Queen: The legendary rock band literally named their most famous album after this movie. Freddie Mercury and the guys were huge fans of the film's blend of high art and absurdity.

- Bugs Bunny: The "anarchic trickster" energy of Harpo and Groucho heavily influenced the early animators at Warner Bros.

- Modern Sitcoms: Shows like Seinfeld or Arrested Development rely on the same kind of "escalation of absurdity" that the Marx Brothers perfected here.

The film was an instant hit. It made over $3 million at the box office, which was a massive sum in 1935. It proved that the brothers could be mainstream stars without losing their edge. It also, unfortunately, set a template that MGM would eventually over-rely on. Later films like A Day at the Races or At the Circus tried to copy the "Night at the Opera" formula a little too closely, eventually leading to a bit of burnout.

✨ Don't miss: Why Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy Actors Still Define the Modern Spy Thriller

Common Misconceptions About the Film

Some film historians argue that MGM "neutered" the brothers. They say that by making them nicer and adding the romantic subplots, the studio stripped away the pure anarchy of their earlier work like Horse Feathers.

I disagree.

If anything, the constraints of the MGM system made the comedy sharper. When you have a solid plot, the jokes have something to push against. In their earlier movies, the plot was so thin that the jokes sometimes felt like they were happening in a vacuum. In A Night at the Opera 1935, the jokes feel like a rebellion. That’s a much stronger comedic hook.

Also, people often forget how much of a technical challenge this movie was. Recording sound in 1935 was still tricky, especially with actors who liked to ad-lib and run around the set. The cinematography by Merritt B. Gerstad had to capture lightning in a bottle.

Actionable Insights for the Modern Viewer

If you're going to watch A Night at the Opera 1935 for the first time, or even the tenth, here is how to get the most out of it:

- Watch the Backgrounds: In the stateroom scene, don't just watch Groucho. Watch the people in the back. The sheer physical effort required to keep that scene from collapsing into actual injuries is impressive.

- Listen for the Puns: Chico’s "logic" is actually very consistent. He isn't being dumb; he’s applying a completely different set of rules to the English language.

- Contextualize the Villain: To really enjoy the ending, you have to understand how much 1930s audiences loathed "stuffed shirts." The character of Lassparri isn't just a bad guy; he’s a symbol of the unearned ego of the upper class.

- Skip the History Books, Just Watch: Don't get bogged down in the "importance" of the film. It's a comedy. If you aren't laughing, you're doing it wrong. Turn off your phone, ignore the "dated" aspects of the 1930s production, and just let the chaos wash over you.

The movie isn't just a classic because it's old. It's a classic because it's actually, genuinely funny. Most comedies from five years ago feel dated today. This one is nearly 90 years old and still hits like a freight train.

Next Steps:

Go find the "Contract Scene" on YouTube. It’s the perfect entry point. If you find yourself smiling at "The party of the first part," then go rent the full movie. You won't regret it. After that, look into the 1937 follow-up A Day at the Races to see the brothers at the absolute peak of their MGM-era polish.