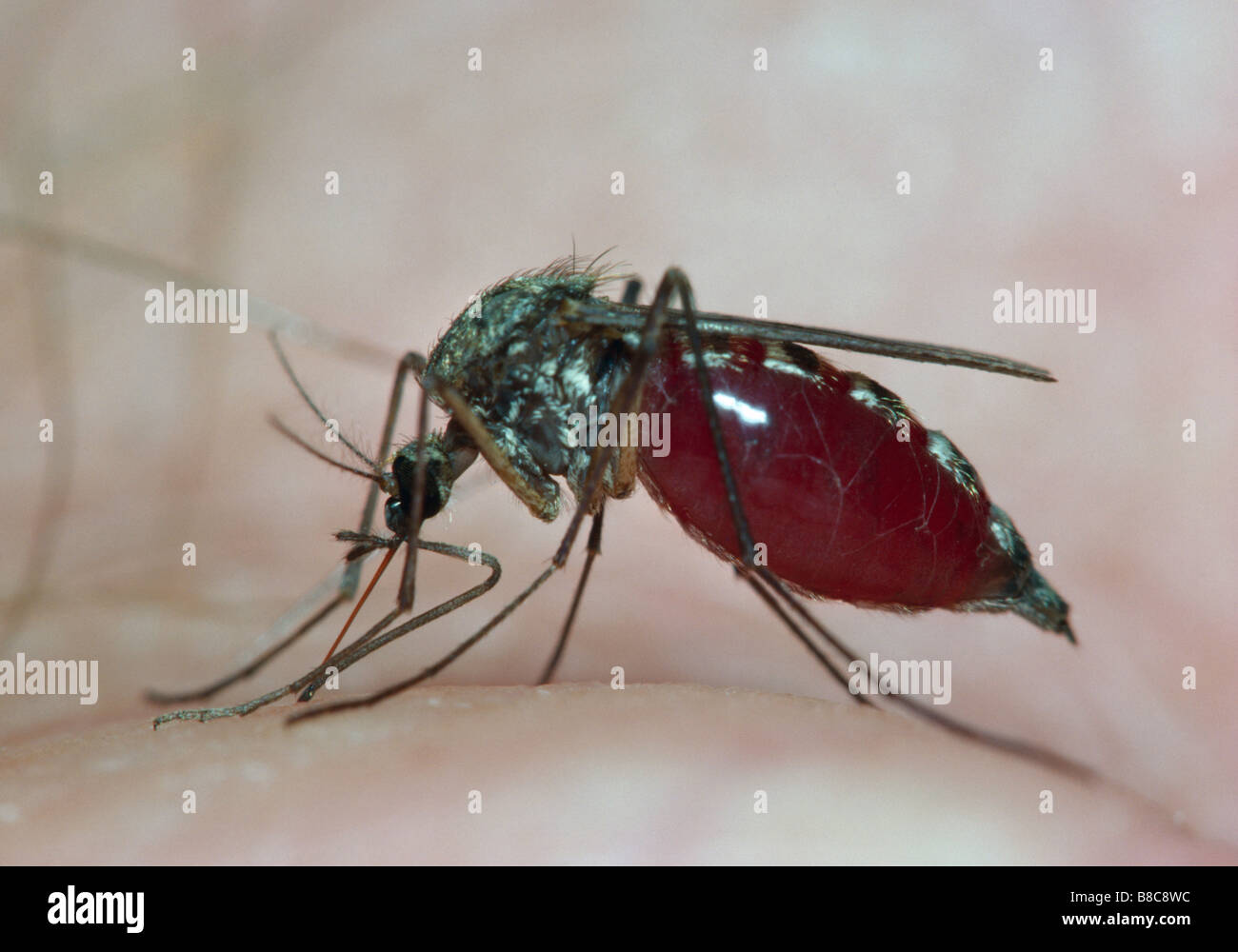

It starts with a high-pitched whine that sounds like a tiny, broken violin. You swat at your ear, but you’re usually too late. By the time you feel that localized prick, the crime is already in progress. We tend to think of a mosquito biting a human as a simple poke with a needle, like a doctor giving a vaccine, but the reality is much more gruesome and impressively complex. It’s actually a multi-stage surgical extraction performed by a creature that has spent millions of years perfecting the art of stealing your blood without you noticing—at least for the first few minutes.

Honestly, it’s kind of a miracle we don’t feel it instantly. The mosquito’s "needle" isn't one solid piece. It’s a toolset called a proboscis, consisting of six different needles (stylets) that serve very specific roles. Two of them have tiny teeth to saw through your skin. Two others hold the tissues apart so the "straw" can get in there. It’s a messy, microscopic construction site happening right on your forearm.

The mechanics of the mosquito biting a human

When a mosquito lands, she—and it is always a she, because males only drink nectar—isn't just looking for a snack. She needs the protein and iron in your blood to produce eggs. She’s a mother on a mission, though that doesn't make the itchy welt any less annoying.

The process is fascinatingly surgical. Once those serrated mandibles saw through the epidermis, the mosquito begins a frantic search for a blood vessel. She doesn't just hit a vein on the first try like a trained phlebotomist. Instead, the flexible labrum probes around in your skin, bending at wild angles until it find a capillary.

Research published in PLOS Pathogens and observed through high-resolution microscopy shows that these needles are incredibly flexible. They can turn 90 degrees under your skin. It’s a hunt. And while she’s hunting, she’s doing something even more devious: she’s spitting into you.

Why the itch happens (The Saliva Problem)

You aren't actually allergic to the mosquito's "bite" in the traditional sense. You’re reacting to her spit. Mosquito saliva is a chemical cocktail designed to make the heist go smoothly. It contains anticoagulants that keep your blood from clotting, because a clogged straw would mean a dead mosquito. It also contains local anesthetics so you don't feel the initial intrusion and slap her into oblivion.

Basically, her spit is the reason you can sit there for three minutes while she doubles her body weight in your blood. Your immune system eventually recognizes these foreign proteins and releases histamine. That’s the "red alert" signal that causes the swelling, redness, and that maddening itch.

It isn't just "sweet blood" (What attracts them)

You’ve heard people say they have "sweet blood." Maybe you're the person who gets eaten alive at a BBQ while your friend doesn't have a single mark. It isn't a myth. Mosquitoes are picky eaters.

💡 You might also like: Why Positive Quotes About Anger Are Actually Better Than Calmness

They use a combination of thermal sensors, visual cues, and chemical "smell" to find a target. Carbon dioxide is the big one. Every time you exhale, you’re sending out a long-range beacon. If you’re exercising or drinking a beer—yes, a study in the Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association actually found that beer consumption increases mosquito attraction—you’re basically lighting up like a neon sign in the dark.

- Lactic Acid: If you’ve just worked out, you’re covered in it. They love it.

- Blood Type: Some studies, including famous ones from the Journal of Medical Entomology, suggest people with Type O blood are roughly twice as attractive to Aedes albopictus (the Asian tiger mosquito) as those with Type A.

- Skin Microbiome: The specific bacteria living on your skin dictate your "scent profile." Some people produce natural repellents, while others produce a scent that mosquitoes find irresistible. It’s a genetic lottery you didn't ask to enter.

The darker side of the bite

We treat it as a nuisance, but a mosquito biting a human is technically the deadliest animal interaction on Earth. It isn't the mosquito that kills; it's the hitchhikers.

When that mosquito spits her anticoagulant into your bloodstream, she might also be offloading parasites or viruses. We’re talking about Malaria, Dengue fever, Zika, and West Nile. According to the World Health Organization, mosquito-borne diseases cause more than 700,000 deaths annually. In the U.S., we mostly worry about West Nile or EEE (Eastern Equine Encephalitis), which are rare but can be devastating.

The nuance here is that not every mosquito carries disease. In fact, most don't. But the biological mechanism—the exchange of fluids—is what makes them such effective vectors. They are the ultimate "dirty needles" of the animal kingdom.

Why can't we just kill them all?

It’s a tempting thought. If we wiped out every mosquito, would the ecosystem collapse? Biologists like Jonti Reid and others have debated this for years. While some birds and bats eat them, mosquitoes aren't usually the primary food source for any single predator. However, their larvae are huge players in aquatic ecosystems, feeding fish and filtering organic matter. Total eradication is a massive ecological gamble that most scientists are hesitant to take, even with new CRISPR gene-drive technology that could potentially sterilize entire populations.

How to actually stop the bite

Forget the "life hacks" you see on social media. Rubbing a dryer sheet on your skin or eating mountains of garlic won't do a thing. If you want to stop a mosquito biting a human, you have to look at what the science actually supports.

The CDC and EPA are pretty clear on this. DEET is still the gold standard, though picaridin is a fantastic alternative if you hate the greasy feeling of DEET. Picaridin is synthetic but modeled after a compound found in pepper plants. It’s odorless and doesn't melt your plastic gear, which is a big plus for hikers.

If you’re looking for a "natural" route, Oil of Lemon Eucalyptus (OLE) is the only plant-based repellent that consistently performs alongside the heavy-duty chemicals in peer-reviewed testing. But remember, "pure" lemon eucalyptus essential oil is NOT the same thing as the EPA-registered repellent OLE; the concentrations are totally different.

Practical Steps for Protection

- Dump the water: It takes less than a tablespoon of standing water for a mosquito to lay eggs. Check your gutters, old tires, and even the saucers under your potted plants. Do it every three days.

- Timing is everything: Most species, like the Anopheles, are most active at dawn and dusk. If you’re outside then, wear long sleeves.

- Fan power: Mosquitoes are notoriously weak fliers. A simple oscillating fan on your patio creates enough turbulence to make it nearly impossible for them to land on you. It’s the lowest-tech, most effective solution for outdoor seating.

- Treat your clothes: If you’re going into the deep woods, use Permethrin. You spray it on your clothes (not your skin), and it stays effective through several washes. It doesn't just repel; it kills mosquitoes on contact.

Dealing with the aftermath

If you’ve already been bitten, stop scratching. I know, it’s impossible advice. But scratching creates micro-tears in the skin that can lead to secondary bacterial infections like cellulitis.

A cold compress can help constrict the blood vessels and reduce the spread of the saliva proteins. Hydrocortisone cream or a paste of baking soda and water are the old-school remedies that actually work by neutralizing the inflammatory response. Some people swear by the "suction" tools designed to suck out the saliva, but the clinical evidence on those is a bit shaky—by the time you use it, the saliva has usually already integrated into your tissue.

The most important thing to watch for isn't the itch; it's the systemic reaction. If a bite is followed by a high fever, severe headache, or body aches, that’s when you need to see a doctor. It's rare in many parts of the world, but it’s the one time a mosquito bite graduates from an annoyance to a medical priority.

Basically, the best defense is making yourself as "invisible" as possible to their chemical sensors. Keep the air moving, keep the DEET handy, and stop giving them a free place to breed in your backyard.