Some movies just feel like a long, warm afternoon in a graveyard. That sounds morbid, I know. But if you’ve actually sat down with the 1987 classic A Month in the Country, you know exactly what I’m talking about. It is a quiet, devastatingly beautiful piece of cinema that captures the shell-shocked stillness of England after the Great War better than almost anything else. It doesn’t rely on explosions or over-the-top trauma. It’s just two men in a field, digging up the past—literally and figuratively.

Honestly, it’s a miracle this movie even exists in a watchable format today. For years, it was basically a lost film. The original 35mm prints went missing, and for a long time, fans had to settle for grainy, low-quality bootlegs that looked like they were filmed through a tea bag. It wasn't until the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences helped track down the original film elements that we got the crisp, beautiful restoration we have now. Watching it today, you can finally see the dust motes dancing in the light of that medieval church, and it makes all the difference.

What Actually Happens in A Month in the Country?

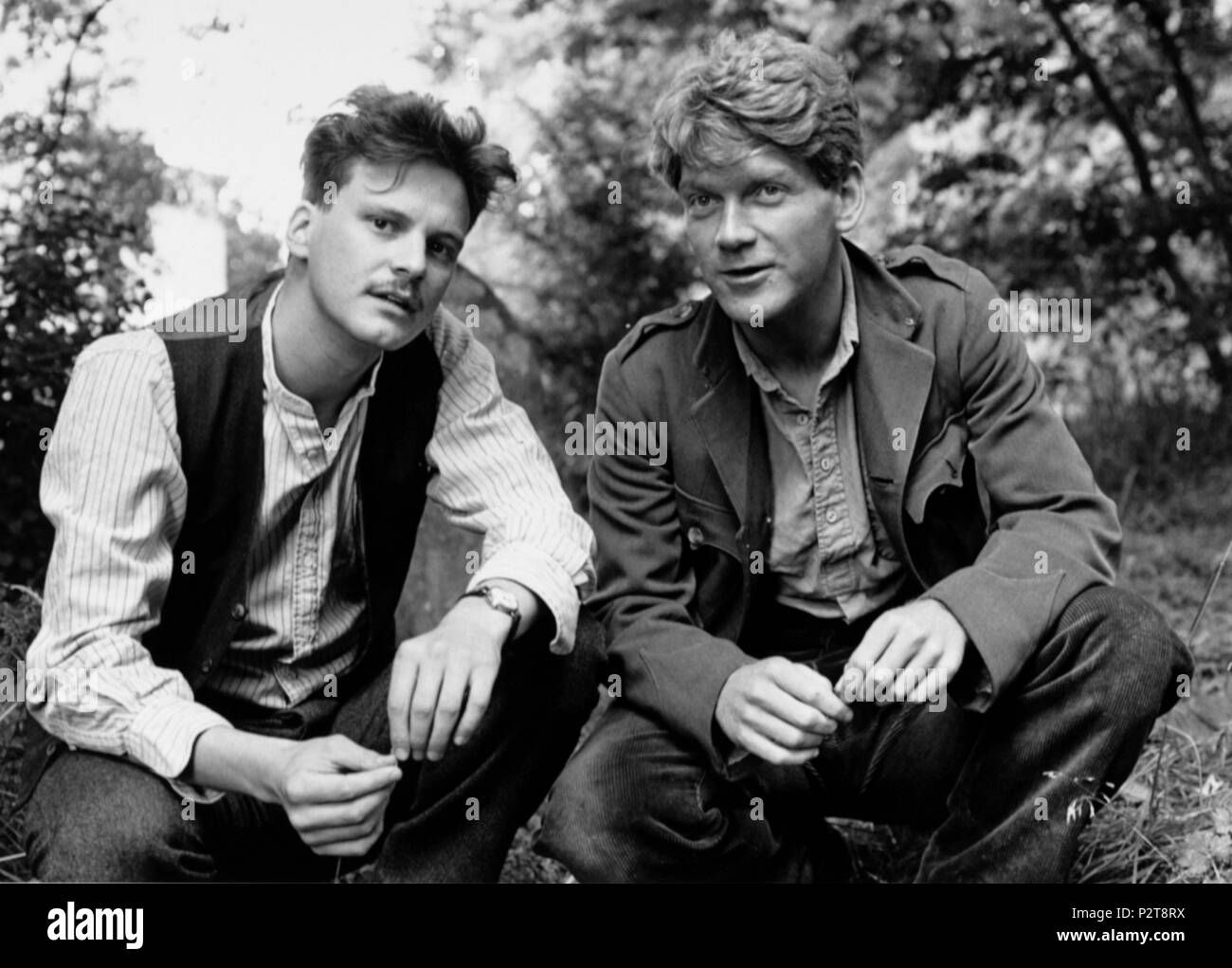

The plot is deceptively simple. It’s 1920. Tom Birkin, played by a very young, very twitchy Colin Firth, arrives in the tiny village of Oxgodby. He’s a survivor of the Battle of Passchendaele, and he’s got a persistent facial tic and a shattered soul to prove it. He’s been hired to uncover a medieval mural hidden under layers of whitewash on the wall of the local church.

While he’s living in the belfry, he meets another veteran, Moon, played by Kenneth Branagh. Moon is digging for a lost grave outside the churchyard. These two men are basically orbiting the same central void. They are both trying to find something lost in the dirt because they can't figure out how to live in the present.

The Mural as a Metaphor

The mural isn't just a painting. As Birkin painstakingly scrapes away the plaster, he reveals a "Doom" painting—a depiction of the Last Judgment. It’s vibrant. It’s terrifying. And it’s a direct mirror to the hell Birkin just climbed out of in the trenches.

The film manages to be incredibly romantic without ever really being a romance. There’s a subplot involving the vicar’s wife, Alice Keach (played by Natasha Richardson), but it’s mostly about the possibility of love. It’s about that agonizing feeling of seeing something beautiful and knowing you can’t have it because you’re too broken to hold it. It’s subtle stuff. You have to watch their eyes. Firth is incredible here; he conveys so much with just a flinch or a hesitant look.

✨ Don't miss: Why the Cast of Hold Your Breath 2024 Makes This Dust Bowl Horror Actually Work

Why the 1980s Produced Such a Specific Vibe

There was this specific wave of British filmmaking in the late 80s that focused on the "heritage" aesthetic, but A Month in the Country feels different from the polished Merchant Ivory productions like A Room with a View. It’s dirtier. It feels more honest. Pat O'Connor, the director, chose to emphasize the heat of that particular summer. You can almost feel the sweat and the itchy wool suits.

The score by Howard Blake is also a huge part of why this film sticks in your brain. It’s melancholy but soaring. It captures that specific English "pastoral" feeling—the idea that the countryside is beautiful, but it’s built on top of centuries of grief.

- The Cast: You’ve got Firth and Branagh before they were "Sir Kenneth" and "Mr. Darcy." They were just hungry actors back then.

- The Source Material: It’s based on the novel by J.L. Carr. If you haven't read it, you should. It’s tiny, maybe 100 pages, but it packs a wallop.

- The Cinematography: Kenneth MacMillan (who did Henry V) makes the Yorkshire landscape look like a painting itself.

The Tragedy of the "Lost" Film

For a while, the history of A Month in the Country was more dramatic than the movie itself. Because of rights issues and the folding of the original production company, the master negative was lost. People thought it was gone forever. It wasn't until 2004 that a print was found in a vault in the United States.

This is why the movie has such a cult following. For two decades, it was a "if you know, you know" situation. Film students talked about it in hushed tones. Finding a copy was like finding a secret map. When it was finally released on Blu-ray by Twilight Time and later by the BFI, it was a major event for cinephiles. It’s rare that a "lost" movie actually lives up to the hype once it's found. This one did.

Realism Over Melodrama

One thing people get wrong about this movie is expecting a big emotional payoff. It doesn't give you that. It’s a film about "the one that got away"—not just the woman, but the life Birkin could have had if the war hadn't happened.

🔗 Read more: Is Steven Weber Leaving Chicago Med? What Really Happened With Dean Archer

It handles PTSD (then called shell shock) with a very light touch. Birkin stammers. He has nightmares. He’s socially awkward. But the movie doesn't treat him like a victim. It treats him like a craftsman. There’s something deeply therapeutic about watching him work on that mural. The slow, methodical process of restoration becomes a process of self-healing.

I’ve heard people complain that "nothing happens." If you need car chases, yeah, you're going to be bored. But if you care about the tension between two people sharing a cigarette in the rain, or the way a specific shade of red paint can break a man's heart, this is your movie.

Comparing the Film to the Book

J.L. Carr’s book is arguably a masterpiece of 20th-century literature. The film stays remarkably faithful to it, which is rare. Simon Gray wrote the screenplay, and he understood that the power of the story is in the silence. He kept Carr’s first-person perspective by using a framing device—an older Birkin looking back—which gives the whole thing a nostalgic, golden-hour glow.

One interesting change is the character of Moon. In the book, his trauma feels a bit more abstract. In the film, Branagh brings a certain frantic energy to the role that makes the ending even more painful. You realize that while Birkin is uncovering art, Moon is uncovering a reality he might not be able to handle.

How to Watch It Like an Expert

If you’re going to watch A Month in the Country for the first time, don't watch it on a phone. Don't watch it while scrolling through TikTok. You need to let the rhythm of the film take over.

💡 You might also like: Is Heroes and Villains Legit? What You Need to Know Before Buying

- Look at the light. The way the sun hits the fields in the evening isn't just "pretty." It’s meant to represent a brief window of peace before the world changes again.

- Listen to the silence. The sound design uses ambient noise—birds, wind, the scraping of a spatula—to ground the story.

- Pay attention to the side characters. The village children and the local preacher add layers of "normalcy" that contrast with the brokenness of the two main men.

The Lasting Legacy of Oxgodby

What really happened with this film is that it became a template for the "quiet British drama." It proved you could tell a massive story about the aftermath of a world-changing event through a very small, intimate lens. It’s a movie that rewards repeat viewings because once you know the ending, you see the clues throughout. You see the way Alice Keach looks at Birkin with a mix of pity and longing. You see the way Moon hides his hands when they shake.

It’s a perfect film. Truly. It’s short, it’s focused, and it doesn't waste a single frame.

Actionable Next Steps

If this sparked your interest, here is how to actually dive deeper into this specific corner of cinema history:

- Track down the BFI Blu-ray: If you can find it, the restoration is vastly superior to any streaming version you might find on a random platform. The colors in the mural need to be seen in high definition to understand Birkin's obsession.

- Read J.L. Carr’s novel: It’s a quick read, often cited as one of the best "short novels" ever written. It provides a deeper internal monologue for Birkin that clarifies some of his weirder decisions in the film.

- Explore the "Lost Films" archives: If the story of the film’s disappearance interested you, check out the British Film Institute’s "Most Wanted" list. It’s a fascinating rabbit hole of cinematic history that is still missing.

- Watch 'The Go-Between' (1971): If you liked the atmosphere of A Month in the Country, this is its spiritual cousin. It deals with similar themes of memory, heat, and the English class system during the same era.