You’ve seen it a thousand times. It’s plastered on classroom walls, tucked into the back of old diaries, and currently serves as the background for about half the "digital nomad" laptops in every coffee shop from Lisbon to Bali. A map with all continents and oceans seems like the simplest thing in the world. Water is blue, land is green or brown, and everything stays where it belongs. Right?

Actually, it’s a mess.

The moment you try to flatten a sphere onto a rectangular piece of paper, you’re basically lying. You have to be. It’s mathematically impossible to preserve the shape, size, and direction of our planet all at once. If you want the continents to look "right," the oceans get stretched. If you want the ocean navigation to be accurate, Greenland ends up looking bigger than Africa—which is a total lie, by the way. Africa is actually fourteen times larger than Greenland.

The Seven (or Six, or Five) Continent Problem

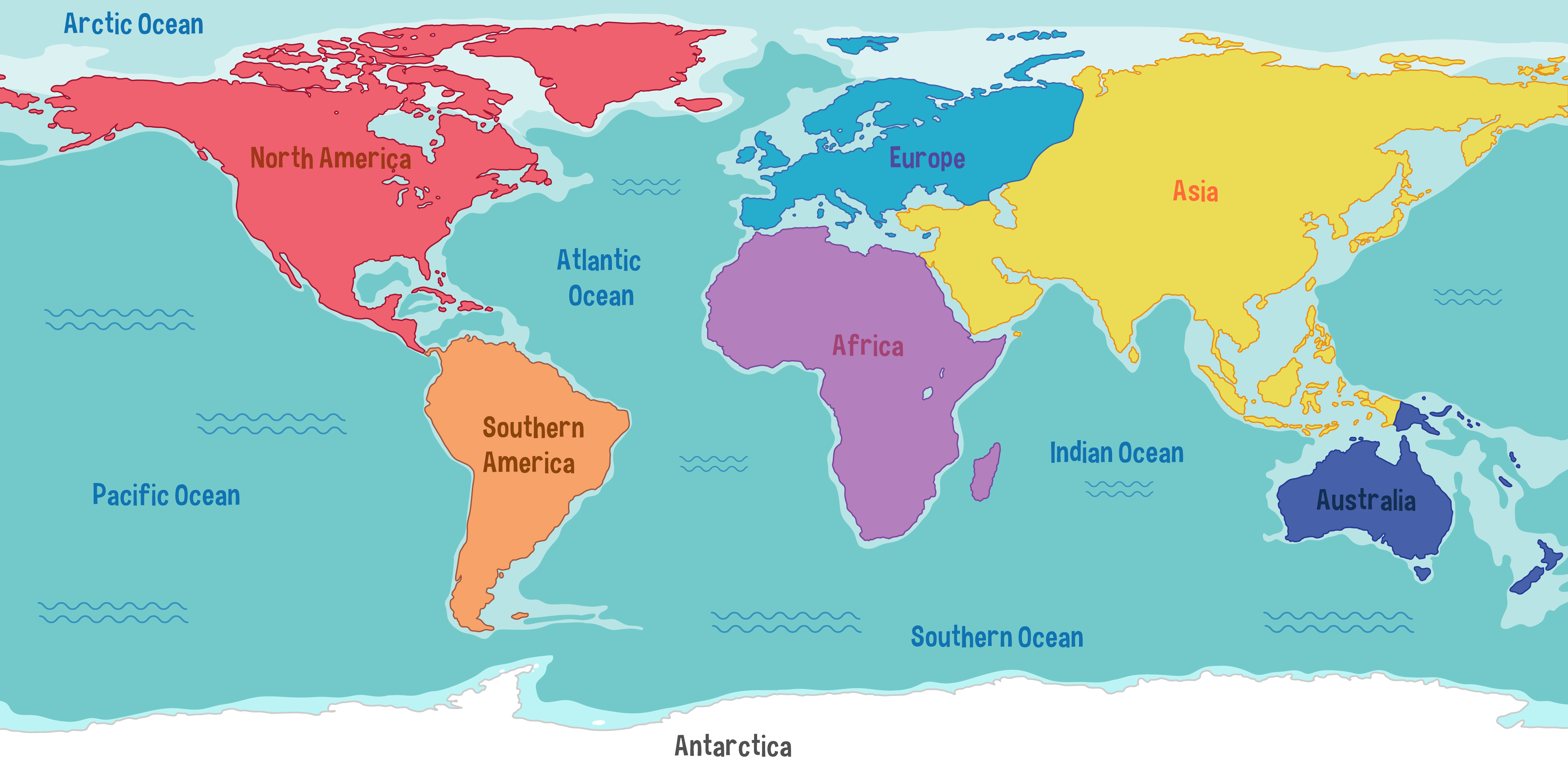

Let’s talk about the land. Most of us grew up learning the "Seven Continents" model: North America, South America, Europe, Asia, Africa, Australia, and Antarctica. But honestly, that’s just one way to look at a map with all continents and oceans.

Geology doesn't care about our borders. If you look at a tectonic plate map, Europe and Asia are just one giant slab of rock called Eurasia. There is no physical ocean separating them—just the Ural Mountains, which, in the grand scheme of planetary science, is a pretty arbitrary place to draw a line. In many Latin American schools, students are taught that North and South America are a single continent called "America." Then you’ve got the Olympic rings, which represent five continents because they don't count Antarctica (nobody lives there permanently) and they combine the Americas.

It gets weirder. Have you heard of Zealandia? Geologists basically confirmed a few years ago that there is a massive eighth continent mostly submerged under the Pacific Ocean. New Zealand is just the tip of it. So, when you look at a standard map with all continents and oceans, you're looking at a simplified version of a much more chaotic reality.

📖 Related: Why San Luis Valley Colorado is the Weirdest, Most Beautiful Place You’ve Never Been

The Five Oceans: Why the Map Changed Recently

For the longest time, we had four. Atlantic, Pacific, Indian, and Arctic. That was the standard. But if you buy a map with all continents and oceans produced after 2021, you’ll likely see a fifth: the Southern Ocean.

The National Geographic Society officially recognized the Southern Ocean a few years back, encircling Antarctica. It’s not defined by land boundaries like the others. Instead, it’s defined by the Antarctic Circumpolar Current. This is cold, dense water that zips around the bottom of the world, keeping Antarctica frozen. It’s a biological distinct zone, home to thousands of species that don't live anywhere else.

The Pacific remains the king of the map. It’s so big it could swallow all the land on Earth and still have room for another Africa. If you look at a map centered on the Pacific, you realize just how much of our planet is just... blue.

Projections: The Mercator Trap

Most map with all continents and oceans versions use the Mercator projection. This was designed in 1569 by Gerardus Mercator. It was a tool for sailors. Because it keeps lines of constant bearing straight, a navigator could draw a line between two points and follow a compass.

But it’s terrible for visual accuracy.

👉 See also: Why Palacio da Anunciada is Lisbon's Most Underrated Luxury Escape

It stretches everything near the poles. This is why Canada and Russia look like they own 80% of the world, while India looks tiny. In reality, India is huge. South America is nearly twice the size of Europe. When we use these maps, we inadvertently develop a skewed sense of global importance based on size.

Alternative projections like the Gall-Peters try to fix this by showing the correct relative sizes of landmasses, but then the shapes look "stretched" and "melting." Then there's the Robinson projection, which tries to compromise by distorting everything just a little bit so nothing looks too crazy. It’s the "participation trophy" of maps.

Hidden Details You Probably Missed

Look closely at the Bering Strait on a map with all continents and oceans. That tiny gap between Russia and Alaska? It’s only about 55 miles wide. During the last Ice Age, people literally walked across it.

Or look at the Atlantic Ocean. It’s actually growing. Every year, the Mid-Atlantic Ridge pushes the Americas away from Europe and Africa by about an inch. It’s slow, but it means every map you’ve ever owned is technically outdated the second it’s printed.

And then there's the "Point Nemo" in the South Pacific. It’s the place in the ocean farthest from any land. It is so isolated that the closest humans to that spot are usually the astronauts on the International Space Station when it passes overhead.

✨ Don't miss: Super 8 Fort Myers Florida: What to Honestly Expect Before You Book

How to Actually Use a Map Today

In a world of GPS and Google Earth, why do we still care about a static map with all continents and oceans? Because it gives us context. GPS is great for finding a Starbucks; it’s terrible for understanding why geopolitical conflicts happen or how weather patterns move.

If you want to understand the world, stop looking at the map as a finished product. Look at it as a snapshot of a moving system.

- Check the Projection: If you're looking at a Mercator map, remind yourself that Africa and South America are much bigger than they look.

- Follow the Ridges: Look for the mountain ranges like the Andes or the Himalayas. They tell you where continents are crashing into each other.

- Trace the Currents: The oceans aren't just puddles; they are "conveyor belts" of heat. The Gulf Stream is why London isn't as cold as Moscow, even though they’re at similar latitudes.

- Compare Sizes: Use tools like "The True Size Of" online to drag countries around and see how they actually compare when you remove the map's distortion.

The world is a sphere. Maps are flat. Until we all start carrying globes in our pockets, we have to live with the compromise. But knowing why the map is distorted makes you a lot smarter than the person who thinks Greenland is the size of a continent.

Get a high-quality physical map—the kind that uses an Equal Earth projection. Hang it up. Every time you see a news story about a far-off place, find it on the map. You’ll start to see the connections between the land, the water, and the people living there. It changes how you see everything.