If you look at a map of the great plains of texas, you’ll see it doesn't just stop at a single line. It's massive. Most people think of Texas and immediately picture the dusty, tumbleweed-strewn deserts of West Texas or the humid, piney woods of the East. But the Great Plains? That’s the real heart of the state. It's a high-altitude plateau that basically feels like the roof of the world when you're standing on it. It’s flat. Unrealistically flat.

Actually, it's tilted.

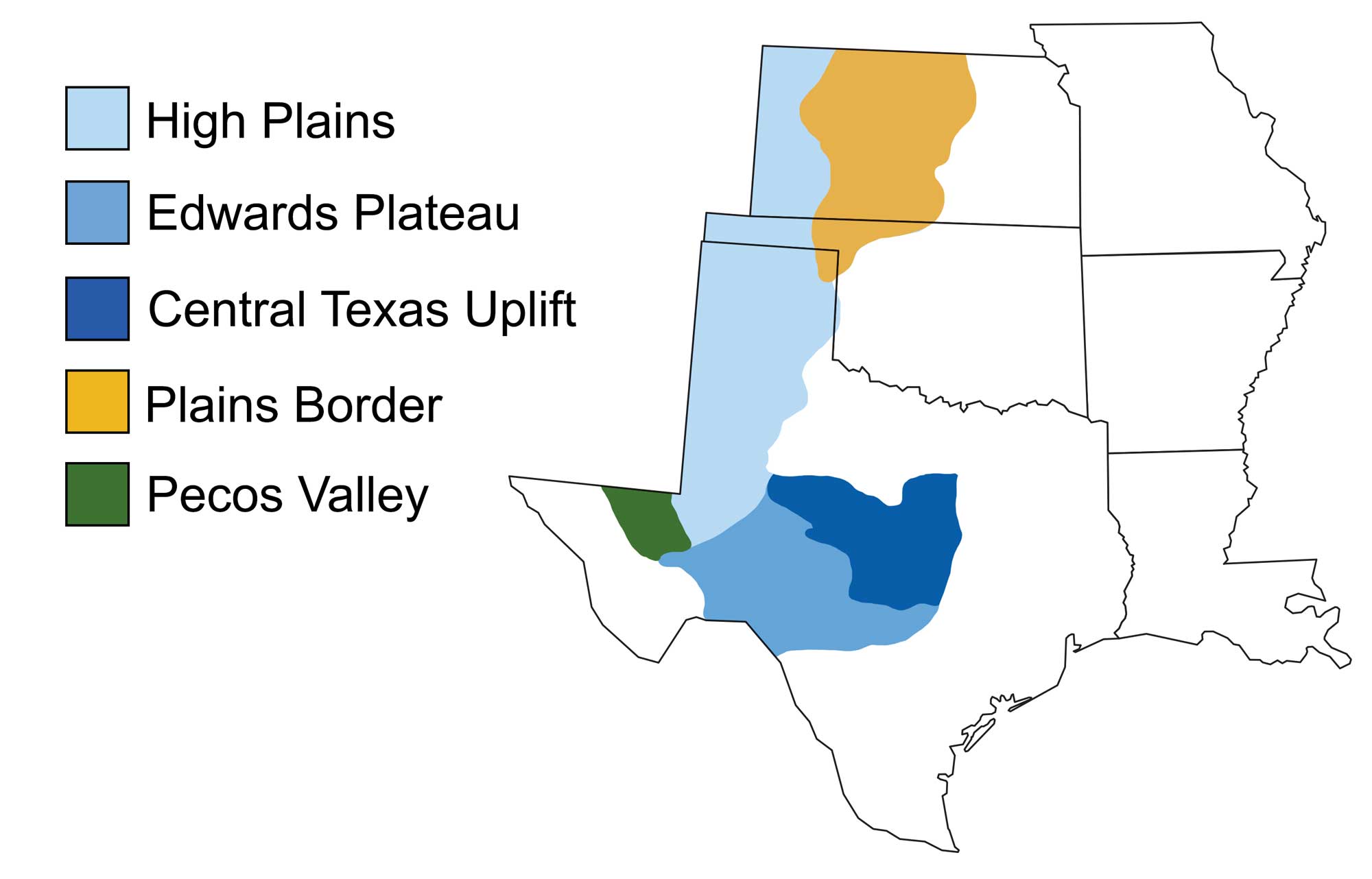

Geologically speaking, the Great Plains of Texas are a massive wedge of sediment. Millions of years ago, the Rockies were eroding, and all that silt and gravel washed down, settling into what we now call the Llano Estacado and the North Central Plains. When you’re looking at a topographical map of the great plains of texas, you're looking at a landscape that rises almost imperceptibly as you head west toward New Mexico.

Where the Lines Actually Fall

The borders aren't just arbitrary lines drawn by a guy in a suit in Austin. They’re dictated by the Balcones Escarpment and the Caprock. To the east, the plains hit the "Rolling Plains," which is exactly what it sounds like—eroded, wavy terrain that eventually gives way to the Hill Country and the Blackland Prairie. To the west, you have the Staked Plains (Llano Estacado), which is one of the largest tablelands in North America.

It's essentially a giant, flat sandwich.

The northern boundary is the Canadian River, which carves a deep, rugged canyon through the panhandle. If you’ve ever driven through Amarillo, you’ve seen the Palo Duro Canyon. It's the "Grand Canyon of Texas." It’s a violent, beautiful gash in an otherwise perfectly level horizon. Honestly, it’s a bit of a shock to the system when you’re driving for four hours through cotton fields and then suddenly the earth just... opens up.

👉 See also: Red Hook Hudson Valley: Why People Are Actually Moving Here (And What They Miss)

The Llano Estacado: A Map Within a Map

Let's talk about the Llano Estacado. It’s the most iconic part of the map of the great plains of texas. Legend has it that early Spanish explorers had to drive stakes into the ground to find their way back because there were no landmarks. No trees. No hills. Just grass and sky.

- The Caprock Canyons: These are the edges. The erosion here is fierce, creating red-clay cliffs that look like something out of a Mars rover photo.

- The Playa Lakes: This is a weird one. The plains are dotted with thousands of small, circular depressions. When it rains, they fill up. When it’s dry, they’re just dusty bowls. They are critical for the Ogallala Aquifer.

- The Ogallala: You can't see it on a physical map, but it’s the most important feature of the Texas Great Plains. It’s a massive underground ocean of fossil water. Without it, the towns of Lubbock and Amarillo basically wouldn't exist as they do today.

Lubbock is often called the "Hub City" because it sits right in the middle of this vast agricultural empire. If you look at a satellite map of the great plains of texas, you'll see a grid. Thousands of perfect circles. Those are center-pivot irrigation systems pulling water from the Ogallala to grow cotton, corn, and sorghum. It's an industrial landscape that somehow manages to feel wild.

The Weather Factor

You can't discuss this region without the wind. On a map, it looks peaceful. In reality, it’s a wind-tunnel. This is the southern end of "Tornado Alley." The flat terrain allows cold fronts from the north to slam into warm, moist air from the Gulf of Mexico. The result? Some of the most spectacular (and terrifying) thunderstorms on the planet.

Wind energy has changed the map too. If you drive through Sweetwater or toward the New Mexico border, the horizon is dominated by thousands of white wind turbines. It’s a weirdly futuristic sight against the backdrop of 19th-century ranching heritage.

Why the Panhandle is the True Great Plains

A lot of folks get the Panhandle confused with the Trans-Pecos. The Trans-Pecos is the mountainous desert around El Paso and Big Bend. That's not the Great Plains. The Panhandle is where the Great Plains truly reside. This is where the buffalo once roamed in herds so large they took days to pass.

✨ Don't miss: Physical Features of the Middle East Map: Why They Define Everything

Specifically, the High Plains sub-region is where the elevation stays consistently high—usually between 3,000 and 4,000 feet. It’s cooler than the rest of Texas. It snows. In Lubbock, you might get a blizzard in January and then be back in short sleeves by March.

Real Evidence of the Landscape’s Power

Look at the history of the Dust Bowl. In the 1930s, this part of the map of the great plains of texas was the epicenter of an environmental disaster. Because the land is so flat and the wind is so constant, once the native grasses were plowed up for wheat, there was nothing to hold the soil down. The "Black Blizzards" were literally the topsoil of Texas blowing all the way to Washington D.C.

Today, conservation efforts like the USDA’s Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) have helped put some of that grass back. It’s a more stable map now, but it’s still a fragile ecosystem.

How to Read the Texas Plains Like an Expert

If you want to understand a map of the great plains of texas, you have to stop looking for mountains. You have to look for the subtle stuff.

- The 100th Meridian: This is the invisible line of longitude that historically separated the humid East from the arid West. It runs right through the Texas Panhandle.

- The Escarpments: Look for the jagged brown lines on the map. These are the "breaks." They mark where the high plateau falls off into the lower plains.

- The Canyons: Palo Duro and Caprock Canyons State Parks are the crown jewels. They provide the verticality in a horizontal world.

The "Permian Basin" is another name you’ll see. While it’s famous for oil, it’s technically the southern extension of the Great Plains. The landscape around Midland and Odessa is the literal bottom of this geographical province. It’s where the high plains start to crumble into the Chihuahuan Desert.

🔗 Read more: Philly to DC Amtrak: What Most People Get Wrong About the Northeast Corridor

Actionable Steps for Exploring the Great Plains of Texas

If you’re planning a trip or just trying to visualize this region better, don't just stick to the interstate. I-40 cuts right through the heart of it, but it doesn't tell the whole story.

- Drive Highway 207: This road takes you through the "breaks" of the Salt Fork of the Brazos River. It’s one of the most scenic, least-traveled roads in the state.

- Visit the Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum: Located in Canyon, Texas, it’s the largest history museum in the state. It explains the geology and the "stakes" of the Llano Estacado better than any textbook.

- Check the Elevation: If you're using a digital map of the great plains of texas, toggle the 3D view. You’ll notice how the land steps down from west to east like a giant staircase.

- Look for the "Lakes": If you're flying over, count the playa lakes. In a wet year, they look like mirrors scattered across a green and brown quilt.

The Texas Great Plains aren't just a place you drive through to get to the mountains. They are a specific, rugged, and historically rich part of the American landscape. They represent the grit of the ranching industry and the massive scale of Texas agriculture. To truly see them, you have to appreciate the horizon. You have to appreciate the fact that out here, the sky is usually the biggest thing on the map.

Understand the geography, and the culture follows. The people who live on the Texas plains are as hardy as the shortgrass that keeps the soil in place. They’ve survived droughts, oil booms, and some of the harshest winters in the South. When you look at that map, remember you’re looking at a place where the earth and sky are in a constant, high-stakes conversation.

Check out the official Texas Parks and Wildlife maps for Caprock Canyons to see the dramatic transition from the High Plains to the Rolling Plains. Look for the "Red Beds"—geological formations that date back to the Permian period, visible in the canyon walls. This is the most direct way to see the "layers" of the Texas plains in person. If you're interested in the agricultural side, the Texas A&M AgriLife Extension maps provide a detailed look at soil types and aquifer depth, which explains why certain crops grow only in specific "pockets" of the panhandle. Use these resources to layer your understanding of the physical terrain with the economic reality of the region.