You’d think looking at a map of the east coast usa would be pretty straightforward. It’s just a line of states hitting the Atlantic, right? Well, not exactly. If you ask a geologist, a historian, and a local from Maine, you’re going to get three wildly different answers about where the "East Coast" actually starts and ends.

It’s huge.

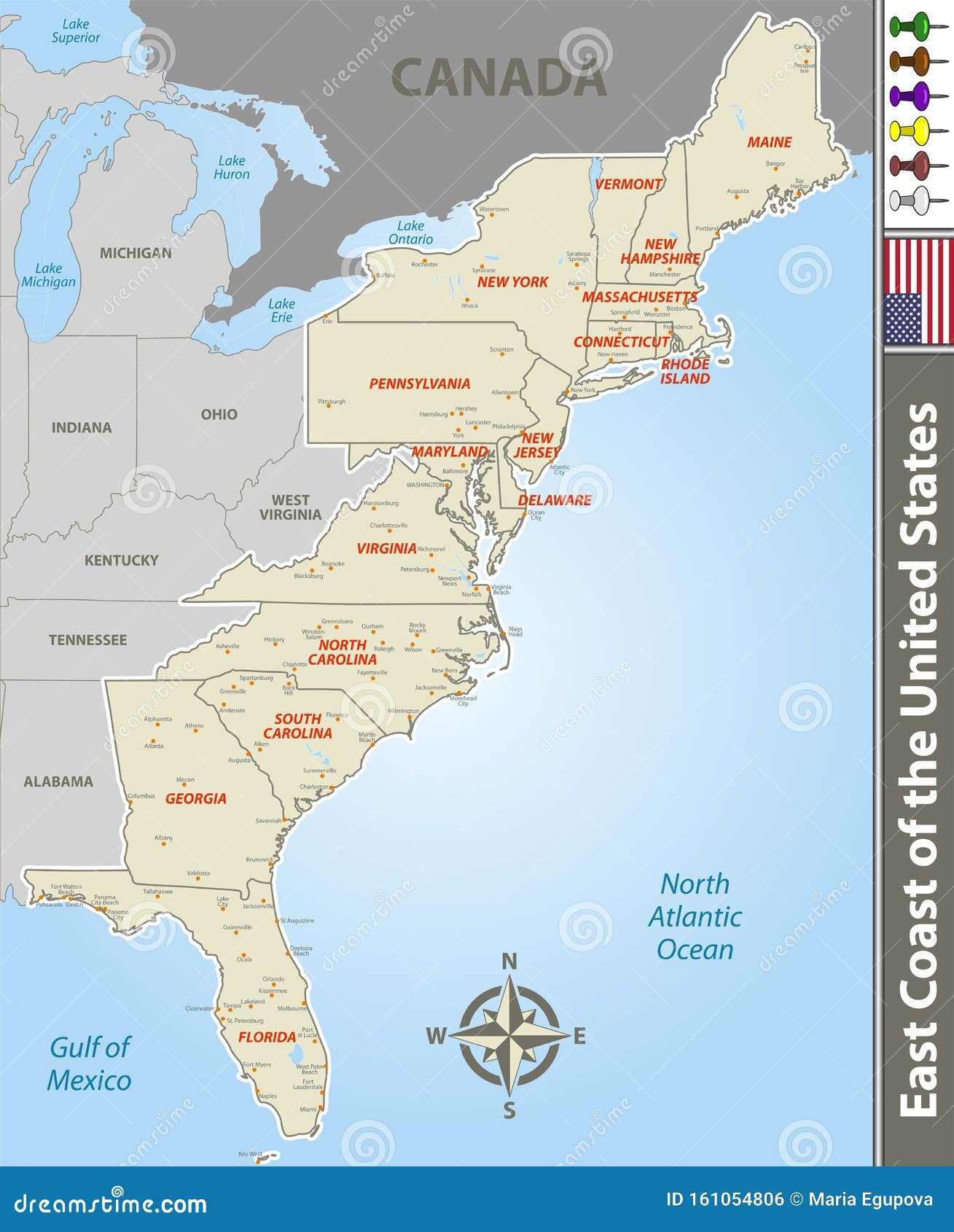

Most people just see a long strip of highway—usually I-95—and call it a day. But that map represents roughly 2,000 miles of coastline, fourteen states, and some of the most ecologically diverse terrain in North America. You’ve got the rugged, glacially-carved granite of Acadia in the north and the literal swampy marshes of the Florida Everglades down south. They have almost nothing in common except the ocean.

The Geography Most People Get Wrong

People argue about the "Triple Point." No, not the thermodynamic one. I'm talking about where the Mid-Atlantic turns into the South. If you’re looking at a map of the east coast usa, the Mason-Dixon line is the historical marker, but culturally? It’s a mess. Maryland and Delaware are the "border states," and depending on who you ask, they belong to the North or the South.

The physical geography is even more nuanced.

North of New York City, the coastline is rocky. It’s jagged. The glaciers during the last ice age basically scraped all the topsoil off and dumped it further south. That’s why Long Island and Cape Cod even exist—they’re basically giant piles of glacial debris known as terminal moraines. If you look closely at a topographical map, you’ll see the "Fall Line." This is where the hard rocks of the Piedmont region meet the softer sedimentary rocks of the Atlantic Coastal Plain. It’s why cities like Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington D.C. are where they are. The waterfalls at the Fall Line stopped ships from going further inland, so people just built cities right there.

🔗 Read more: UNESCO World Heritage Places: What Most People Get Wrong About These Landmarks

It’s clever.

The Interstate 95 Trap

If you’re planning a road trip using a map of the east coast usa, you’ll probably be tempted to stick to I-95. Honestly? That’s usually a mistake if you actually want to see the coast. I-95 is mostly a concrete corridor of gas stations and fast-food joints. To actually see the Atlantic, you have to deviate.

Take US-1 or A1A.

In the Carolinas, the map shows the Outer Banks—a thin, fragile string of barrier islands that look like they’re barely hanging on. And they are. These islands are constantly migrating because of wind and wave action. The Cape Hatteras Lighthouse actually had to be moved in 1999 because the ocean was literally knocking on the front door. This is a recurring theme. From the Jersey Shore down to the Georgia Sea Islands, the map you see today isn't the map that will exist in fifty years. Erosion is a beast.

Beyond the Big Cities

We always talk about the "Megalopolis." That’s the stretch from Boston to D.C. It’s the most densely populated part of the country. On a map of the east coast usa at night, this area glows like a solid neon bar. It’s intense. But if you move your eyes just a few inches on that map, you hit the massive wilderness of the Pine Barrens in New Jersey or the Delmarva Peninsula.

💡 You might also like: Tipos de cangrejos de mar: Lo que nadie te cuenta sobre estos bichos

Delmarva is a weird one.

It’s a single landmass shared by Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia. It feels like a time capsule. While the rest of the corridor is screaming at 80 mph, Delmarva is all chicken farms, oyster boats, and quiet salt marshes. It’s one of the few places where you can still feel what the coast looked like before the skyscrapers took over.

Then there’s the Lowcountry.

South Carolina and Georgia have this incredibly complex network of "barrier islands" and "sea islands." Places like Hilton Head, St. Simons, and Cumberland Island. These aren't just beaches; they are complex ecosystems of live oaks dripping with Spanish moss. The map here gets blurry because the land and water are constantly intermingling. It’s more of a transition zone than a hard border.

The Ecological Divide

When you study a map of the east coast usa, you have to account for the Gulf Stream. This warm ocean current flows up from the Gulf of Mexico, hugging the shoreline until it veers off near Cape Hatteras. This is why the water in Virginia is significantly colder than the water in North Carolina. It’s a massive thermal boundary.

📖 Related: The Rees Hotel Luxury Apartments & Lakeside Residences: Why This Spot Still Wins Queenstown

- Northern Segment: Cold water, rocky bottoms, lobster territory. Think Maine to Cape Cod.

- Central Segment: Sandy beaches, estuaries like the Chesapeake Bay (the largest in the US), and deciduous forests.

- Southern Segment: Subtropical, mangroves in Florida, palm trees, and humid air masses that fuel those massive Atlantic hurricanes.

Speaking of hurricanes, the map is a target. The "Bermuda High"—a high-pressure system—often acts like a steering wheel for storms. Depending on where it sits, it can push a hurricane right into the Outer Banks or steer it harmlessly out to sea.

What the Maps Don't Show You

A map is just a snapshot. What it doesn't show is the tension between development and nature. We’ve paved over a huge portion of the natural wetlands that used to protect the East Coast from storm surges. Now, when a Nor'easter or a hurricane hits, there's nowhere for the water to go.

There's also the "Blue Highway" aspect.

The Intracoastal Waterway (ICW) runs almost the entire length of the coast. It’s a 3,000-mile inland waterway that allows boats to travel without facing the open ocean. If you look at a detailed map of the east coast usa, you’ll see this thin blue line snaking behind the barrier islands. It’s a whole different world back there—slower, quieter, and full of wildlife like manatees and herons.

Actionable Steps for Mapping Your Journey

If you’re using a map of the east coast usa to plan a trip or research the region, don't just look at the land. Look at the water and the elevation.

- Identify the Fall Line cities if you're interested in history. Richmond, D.C., and Philly exist because of the geography.

- Look for the gaps. The spaces between the major cities—like the Adirondacks or the Great Dismal Swamp—are where the real character of the coast survives.

- Check the bathymetry. Understanding how deep the water is off the coast explains why some areas have huge waves (like the Outer Banks) and others have calm bays (like the Chesapeake).

- Use real-time overlays. If you're traveling, use apps that show current wind patterns and tides. The East Coast is defined by its weather more than its roads.

The East Coast isn't a monolith. It’s a collection of fiercely independent regions that just happen to share a shoreline. From the foggy cliffs of Quoddy Head to the turquoise waters of Key West, the map is a lesson in diversity.

Check the topography before you go. Respect the tides. Don't trust I-95 to show you the "real" coast. Get off the main vein and head toward the sound of the surf. You’ll find that the best parts of the map are the ones where the roads finally end at the water's edge.