Bob Dylan was only 21 when he wrote it. That's a weird thought. Most 21-year-olds are figuring out how to pay rent or what to do with a liberal arts degree, but Dylan was sitting in a basement apartment in Greenwich Village, hammering out a six-and-a-half-minute apocalypse on a typewriter. It's 1962. The Cuban Missile Crisis is looming. Everyone thinks the world is about to melt into a radioactive puddle. And then comes A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall.

People call it a protest song. It isn't, really. Not in the "we shall overcome" sense. It’s more like a fever dream or a witness report from someone who just stepped out of a time machine from the future. It’s dense. It’s terrifying. Honestly, it’s kinda beautiful in a way that makes your stomach drop.

The Myth of the Nuclear Fallout

There’s this long-standing rumor that Dylan wrote the song specifically because of the Cuban Missile Crisis. You’ve probably heard it. The story goes that he thought he was going to die and wanted to cram every thought he had into one final poem.

Well, technically, that’s not quite right.

Dylan actually performed the song at Carnegie Hall in late September 1962. The missile crisis didn't truly "break" until October. So, while the vibe of the Cold War was definitely in the air, the specific "we're all going to die tomorrow" panic of October hadn't quite hit yet. He was just sensing the rot in the floorboards earlier than everyone else. He told Nat Hentoff that every line was actually the start of a whole new song that he didn't think he'd have time to write. That’s why the imagery is so packed. It's like a compressed zip file of human suffering.

Breaking Down Those Blue-Eyed Son Lyrics

Who is the blue-eyed son?

Is it Dylan? Is it us? Is it some innocent kid being sent off to a war he doesn't understand?

📖 Related: Isaiah Washington Movies and Shows: Why the Star Still Matters

The song uses a "question and answer" structure borrowed from an old British ballad called "Lord Randall." In the original, a mother asks her son where he’s been, and it turns out he’s been poisoned by his true love. Dylan takes that skeleton and hangs a whole lot of surrealist meat on it.

He talks about a highway of golden with nobody on it. He mentions a black branch with blood that kept drippin’. It’s not just "rain" he’s talking about. It’s a "hard" rain. He famously clarified later that he didn't mean atomic rain specifically, though he admitted it could be interpreted that way. He meant something more general—a heavy, inevitable reckoning for a world that had lost its mind.

Why the Poetry Hits Different

Dylan wasn't just listening to Woody Guthrie when he wrote this. He was reading Arthur Rimbaud. He was looking at the Beat poets.

You can see it in the way the colors pop. Most songs back then were "I love you, you love me" or simple folk tunes. But A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall gives you a "white ladder all covered with water." It gives you "ten thousand talkers whose tongues were all broken."

- The visual scale: He moves from "twelve misty mountains" to "the graveyard of the oceans."

- The auditory nightmare: It's not just things he saw; it's the roar of a wave that could drown the whole world.

- The emotional weight: Meeting a young girl who gave him a rainbow, then seeing a young man who was wounded in love.

It’s a collage. It doesn’t need a linear plot because the world doesn't always have one, especially when it's falling apart.

The Performance That Changed Everything

When Dylan played this at the Gaslight Cafe, people apparently just sat there in stunned silence. It was too long. It was too dark. It didn't have a catchy chorus you could hum while doing the dishes.

👉 See also: Temuera Morrison as Boba Fett: Why Fans Are Still Divided Over the Daimyo of Tatooine

But it changed what a "song" could be.

Before this, pop and folk were mostly about melody and simple messages. After this? You could be a poet. You could be messy. You could use words like "pellets of poison" and "dead ponies" and still get played on the radio—well, eventually.

It’s worth noting that the version on The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan is remarkably stripped back. Just a guitar and that nasal, urgent voice. No drums. No bass. No production tricks to hide behind. It sounds like a guy standing on a street corner shouting about the end of the world because he’s the only one who sees the clouds gathering.

The Patti Smith Moment

If you want to understand the staying power of the song, look at 2016. Dylan wins the Nobel Prize in Literature. He doesn't show up (classic Dylan). Instead, Patti Smith performs A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall.

She gets nervous. She forgets the lyrics. She has to stop and start over.

And honestly? It made the song even more powerful. It showed that these words are heavy. They are hard to carry. Seeing an icon like Patti Smith struggle under the weight of Dylan’s 1962 lyrics proved that the "hard rain" hasn't stopped falling. It's still here. We’re still living in that world.

✨ Don't miss: Why Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy Actors Still Define the Modern Spy Thriller

Is the Rain Still Coming?

We live in a different kind of anxiety now. It’s not just nukes. It’s climate change. It’s the fracturing of truth. It’s the "ten thousand talkers whose tongues were all broken" (which feels like a terrifyingly accurate description of modern social media).

The reason this song stays on every "Greatest of All Time" list isn't just nostalgia. It's because the imagery is universal enough to fit any crisis. When Dylan sings about "the sharp sword in the hands of a child," he’s talking about power without wisdom. That never goes out of style.

What Most People Get Wrong

A lot of critics try to pin down every single line. "Oh, the six frozen highways represent the interstate system." Or "the seven towers" are specific buildings in New York.

Stop.

That’s the wrong way to listen to Dylan. He wasn't writing a map; he was painting a mood. If you try to decode it like a crossword puzzle, you miss the actual feeling of the song. The point is the overload. You’re supposed to feel overwhelmed. You’re supposed to feel like there’s too much horror to process.

Practical Ways to Revisit the Legend

If you've only heard the studio version, you’re missing half the story. Dylan is notorious for changing his songs every time he plays them. He treats them like living things, not museum pieces.

- Check out the version from The Bootleg Series Vol. 4: Bob Dylan Live 1966, The "Royal Albert Hall" Concert. It’s electric, haunting, and much faster. It feels more like a threat than a warning.

- Compare it to the Rolling Thunder Revue version from 1975. He’s wearing white face paint and singing like a punk rocker. The song becomes a theatrical explosion.

- Listen to the lyrics while reading the poetry of Allen Ginsberg. You'll see where the "breath" of the lines comes from.

A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall isn't a song you "finish." It's something you sit with. It’s a reminder that even when things look their absolute worst, there’s a responsibility to "know my song well before I start singin'."

Next Steps for the Dylan Curious

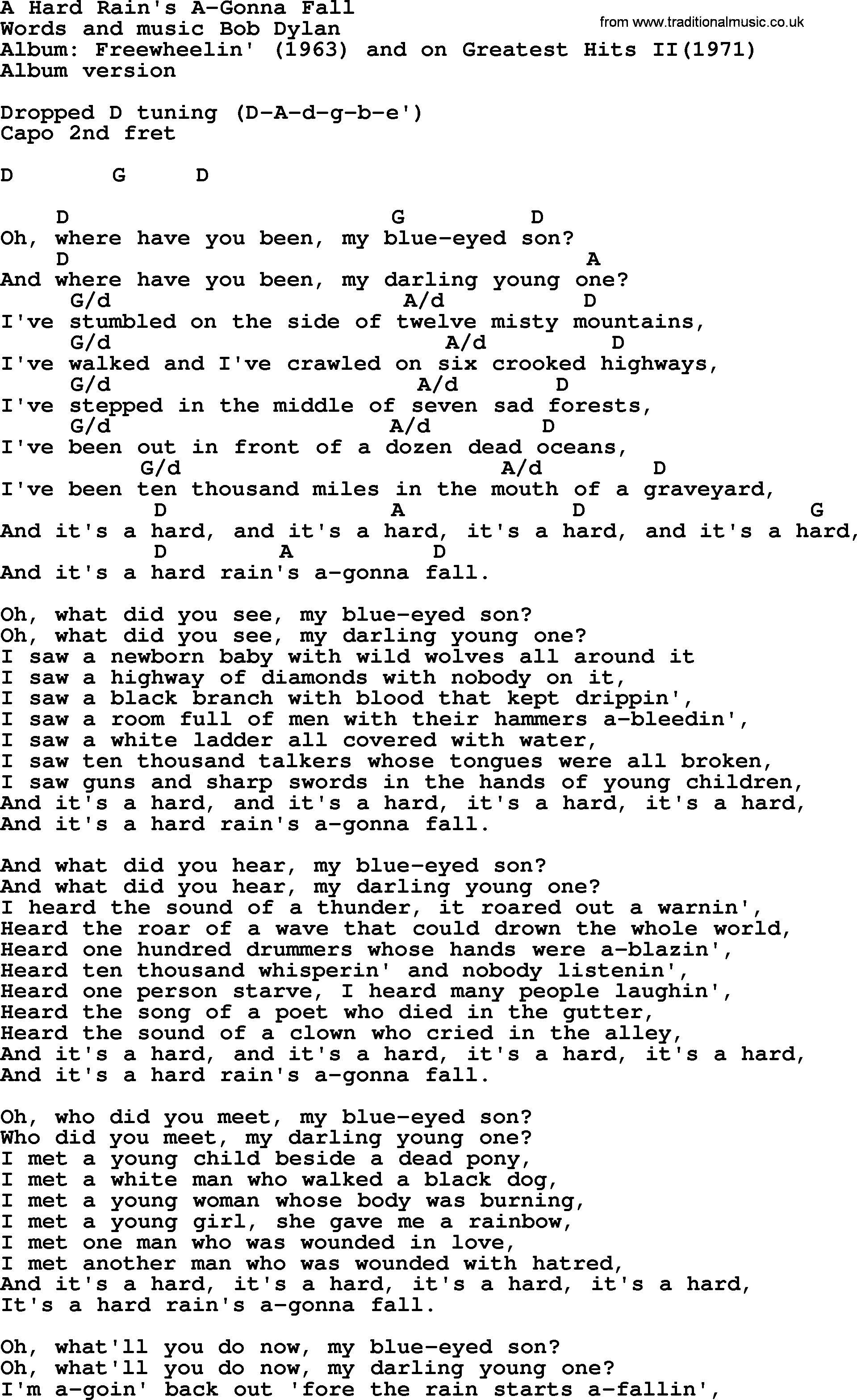

- Listen to the 1963 Studio Version: Focus specifically on the guitar work. It’s simple, but the driving rhythm is what keeps the tension from snapping.

- Read the Lyrics Without Music: Treat it as a standalone poem. Notice how many times he uses the word "and" to stack images on top of one another.

- Explore the Influences: Look up the lyrics to "Lord Randall." Seeing the blueprint Dylan used makes his creative leaps even more impressive.

- Watch the Patti Smith Nobel Performance: It’s on YouTube. It’s raw, it’s human, and it captures the "hard rain" spirit better than almost any polished cover ever could.