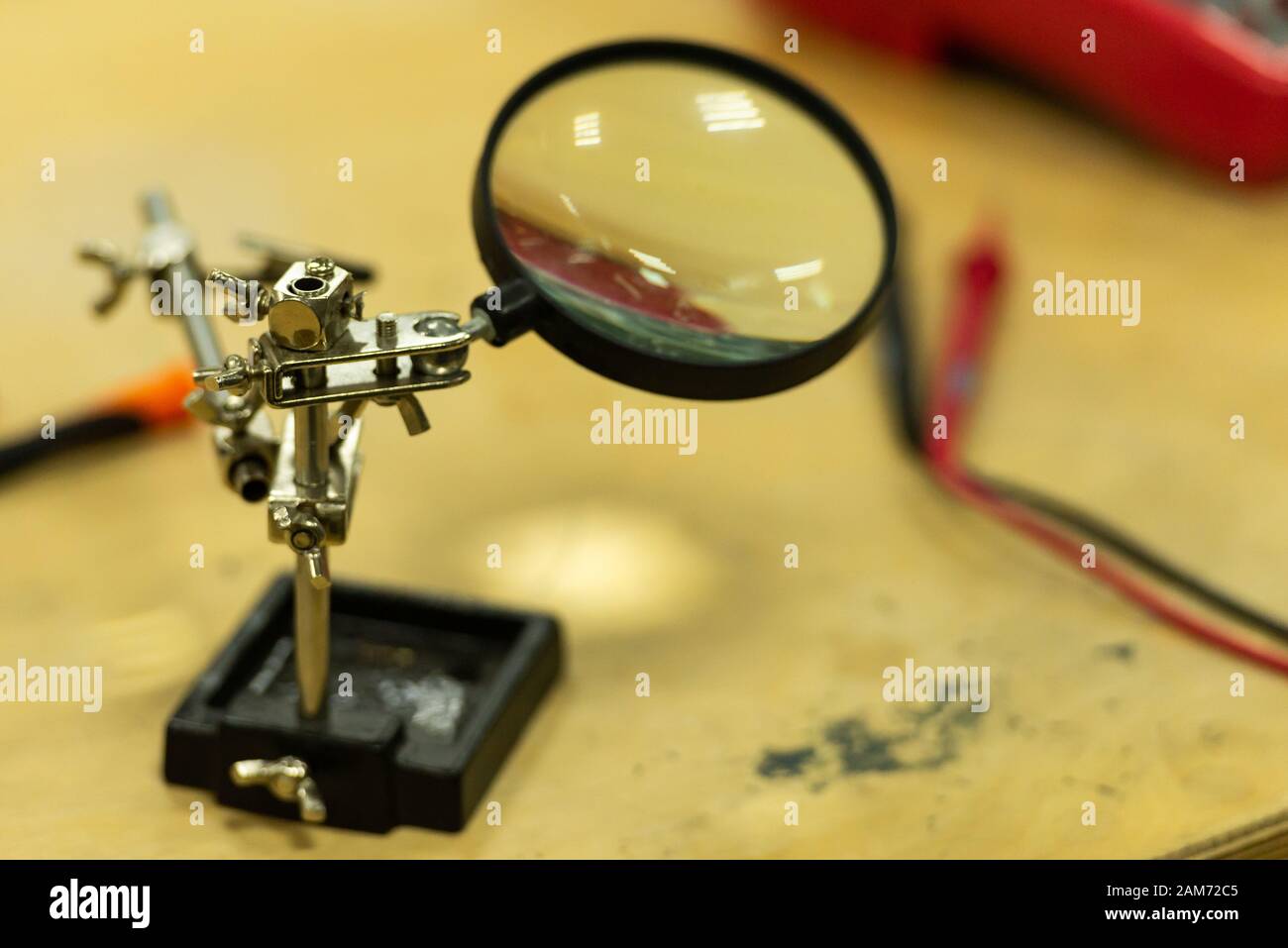

You know that feeling when you're staring at a PCB, holding your breath, trying to drag a tiny bead of solder across two pins that look like they’re miles apart but are actually spaced at 0.5mm? Your neck is craned. Your eyes are watering. You're using one of those classic "helping hands" with the magnifying glass that always sags right when you get close. Honestly, it’s a nightmare. I’ve been there. We've all been there. But things changed when a digital magnifier for soldering actually became affordable for the average hobbyist and pro alike. It isn't just a fancy screen. It’s a literal eye-saver.

Technology moved fast. A few years ago, if you wanted a decent digital setup, you were looking at industrial-grade inspection cameras that cost more than a used car. Now? You can get a high-definition, lag-free station for the price of a decent dinner out. It’s wild. But here’s the thing: most people buy the wrong one because they focus on the "megapixels" or the "zoom level" and forget about the one thing that actually matters when you have a hot iron in your hand.

Latency.

If there is even a millisecond of delay between your hand moving and the image on the screen shifting, you will fail. Your brain can't handle the disconnect. You’ll overcorrect. You’ll bridge pins. You might even melt a connector you weren't supposed to touch. That’s why we need to talk about what actually makes these tools work in a real-world workshop setting.

The Depth of Field Trap

Most beginners think more zoom equals better soldering. Wrong. In fact, it's often the opposite. When you’re zoomed in at 1000x, your depth of field—the area that stays in focus—is thinner than a piece of hair. Move your iron a fraction of a millimeter up, and suddenly the tip is a blurry blob. It’s incredibly frustrating.

A quality digital magnifier for soldering needs a decent working distance. You need room to move your iron, your tweezers, and your hot air flick. If the lens is two inches from the board, you’re going to be bumping into the camera constantly. This is why experts look for "long working distance" (LWD) lenses. Brands like Andonstar or Mustool have dominated this space lately because they figured out that people need about 10 to 15 centimeters of clearance to actually work comfortably.

✨ Don't miss: Samsung Note 8 Release Date: What Really Happened During the Comeback

I remember trying an early USB microscope that plugged into a laptop. The lag was unbearable. I tried to solder a simple 0805 resistor and ended up flicking it across the room because I couldn't tell where my tweezers were in 3D space. That's the dirty secret of cheap digital magnifiers: if it doesn't have its own dedicated screen or a high-speed HDMI output directly to a monitor, it’s probably going to be a paperweight.

Why Your Eyes Are Lying to You

Staring through a traditional optical microscope for eight hours is a recipe for a massive headache. It's called eye fatigue. Your eyes are constantly trying to adjust to the binocular vision. When you switch to a digital magnifier, you're looking at a screen. You can sit up straight. Your posture improves. Your chiropractor will thank you.

But there is a trade-off.

Optical microscopes give you true 3D depth perception. Digital screens are 2D. You have to learn to "read" shadows to understand how high your solder iron is above the joint. It takes about an afternoon of practice to get your "screen legs." Once you do, though, you’ll never want to go back to squinting through a lens.

Lighting is 90% of the Battle

You can have a 4K sensor, but if your lighting is bad, your image will be grainy and useless. Most digital magnifiers come with a ring light around the lens. These are... okay. But they cause a lot of glare on solder joints. Since solder is basically a tiny mirror, the ring light creates a "white-out" effect where you can't actually see the quality of the fillet.

The pro move? Use side lighting.

Angled light creates shadows that define the shape of the solder. It lets you see if the solder has actually wetted the pad or if it’s just sitting there in a "cold joint" ball. If your magnifier doesn't have adjustable "gooseneck" lights, you should probably buy a couple of cheap IKEA desk lamps to supplement it. Seriously. It makes that much of a difference.

The Specs That Actually Matter (And The Ones That Don't)

Don't get tricked by the box. Marketing teams love big numbers. They’ll tell you the camera is "20 Megapixels," but the sensor inside is actually a tiny 2MP chip that’s just upscaling the image. It looks like garbage when you actually use it.

- Refresh Rate: You want 60fps (frames per second). 30fps is usable for inspection, but for active soldering, it feels sluggish.

- Screen Size: A 7-inch integrated screen is the sweet spot. Anything smaller and you’re back to squinting. If it has an HDMI out, you can plug it into a 24-inch monitor and feel like a god.

- Stand Stability: If the stand is plastic, it will wobble. Every time you touch your workbench, the image will shake. Look for a heavy metal base.

- Focus Knob: It should be smooth. If it's "notchy" or stiff, you'll never get that perfect crispness on a tiny SMD component.

Real World Application: Saving a Trashed Trace

Let's look at a real scenario. You’re working on a Nintendo Switch or a modern smartphone. You accidentally rip a pad off the board. To fix this, you need to scrape back the solder mask to reveal the copper trace, which is thinner than a human hair. Then you have to solder a "jumper wire" (usually 0.02mm enamelled copper) to that trace.

Doing this under a standard magnifying glass is nearly impossible for most humans. With a digital magnifier for soldering, you can blow that trace up until it looks like a highway. You can see the exact moment your blade clears the green mask. You can see the solder flow onto the wire. It turns a "this board is dead" moment into a "ten-minute fix."

Is it Better Than a Stereo Microscope?

This is the big debate in the EEVblog forums and among repair techs like Louis Rossmann. A true stereo (binocular) microscope like an AmScope SM-4T is still the gold standard for high-end professional work. Why? Because of that 3D depth perception I mentioned earlier. If you are doing 10 hours of micro-soldering a day, the investment in a high-end optical scope is worth it.

However, for 90% of people—hobbyists, drone builders, keyboard modders, and general electronics repairers—the digital magnifier wins. It’s more portable. It can record video (great for YouTube or showing a client why their device failed). It’s also significantly cheaper. You can get a top-tier digital setup for $200, whereas a good stereo scope starts at $500 and goes up fast once you add lighting and a decent stand.

Maintenance and Longevity

These things live in a harsh environment. Soldering produces fumes. Those fumes are acidic (flux is an acid, after all). Over time, a film will develop on the lens of your camera. If you don't protect it, the lens will eventually cloud up or even melt from the heat rising off your iron.

Always check if your magnifier comes with a replaceable "protector lens" or a UV filter. It’s just a clear piece of glass that screws onto the bottom. If a glob of solder splashes up, it hits the $5 glass, not the $100 camera sensor. If yours doesn't have one, you can usually hack one together or just be very careful with your fume extractor placement.

Speaking of fume extractors—use one. Not just for your lungs, but because the "smoke" from flux will settle on your screen and your lens, making everything look like you're working in a fog bank.

📖 Related: How to Post MP3 to YouTube: Why It’s Not as Simple as You Think

Actionable Steps for Your Next Project

If you're ready to make the jump, don't just buy the first thing you see on an ad.

- Check the stand height first. Make sure you have at least 150mm of space between the lens and the base. Anything less and your soldering iron handle will be hitting the camera.

- Prioritize HDMI output. Even if the unit has a built-in screen, having the option to go to a big monitor is a game-changer for long sessions.

- Ditch the internal battery. Most of these have a small internal battery, but they perform better and the screen is brighter when plugged into a 2A wall wart.

- Update the firmware. It sounds weird for a microscope, but manufacturers like Andonstar often release updates that fix UI bugs or improve color balance.

- Practice "The Shadow Method." Before you work on a real project, take a scrap board. Practice touching specific pins while only looking at the screen. Watch how the shadows move. It’ll train your brain for that 2D-to-3D translation.

Stop struggling with that old magnifying glass. Your eyes are getting tired, and your projects are getting smaller. The shift to digital isn't just a trend; it's a necessary evolution for anyone who wants to keep up with modern electronics. Grab a unit with a solid metal base and a high refresh rate, and you'll wonder how you ever worked without it.