You probably remember that poster. It usually hung right next to the periodic table or the skeleton in the back of the classroom. A giant, pink, fleshy swirl that looked more like a piece of abstract art than a sensory organ. Most of us just memorized the "hammer, anvil, and stirrup" to pass the quiz and then promptly forgot how any of it actually worked. But honestly, if you look at a diagram of the ear with labels today, you’ll realize the mechanics are bordering on the impossible.

It’s tiny. It’s cramped. It is a biological Rube Goldberg machine.

The human ear isn't just a hole in the side of your head. It’s a sophisticated transducer. It takes physical air pressure—literally just molecules bumping into each other—and turns that movement into electrical pulses that your brain interprets as a Taylor Swift song or a car horn. Most people think they "hear" with their ears, but you actually hear with your brain; the ear is just the incredibly fragile hardware that makes the data transfer possible.

Breaking down the outer ear (The Pinna and beyond)

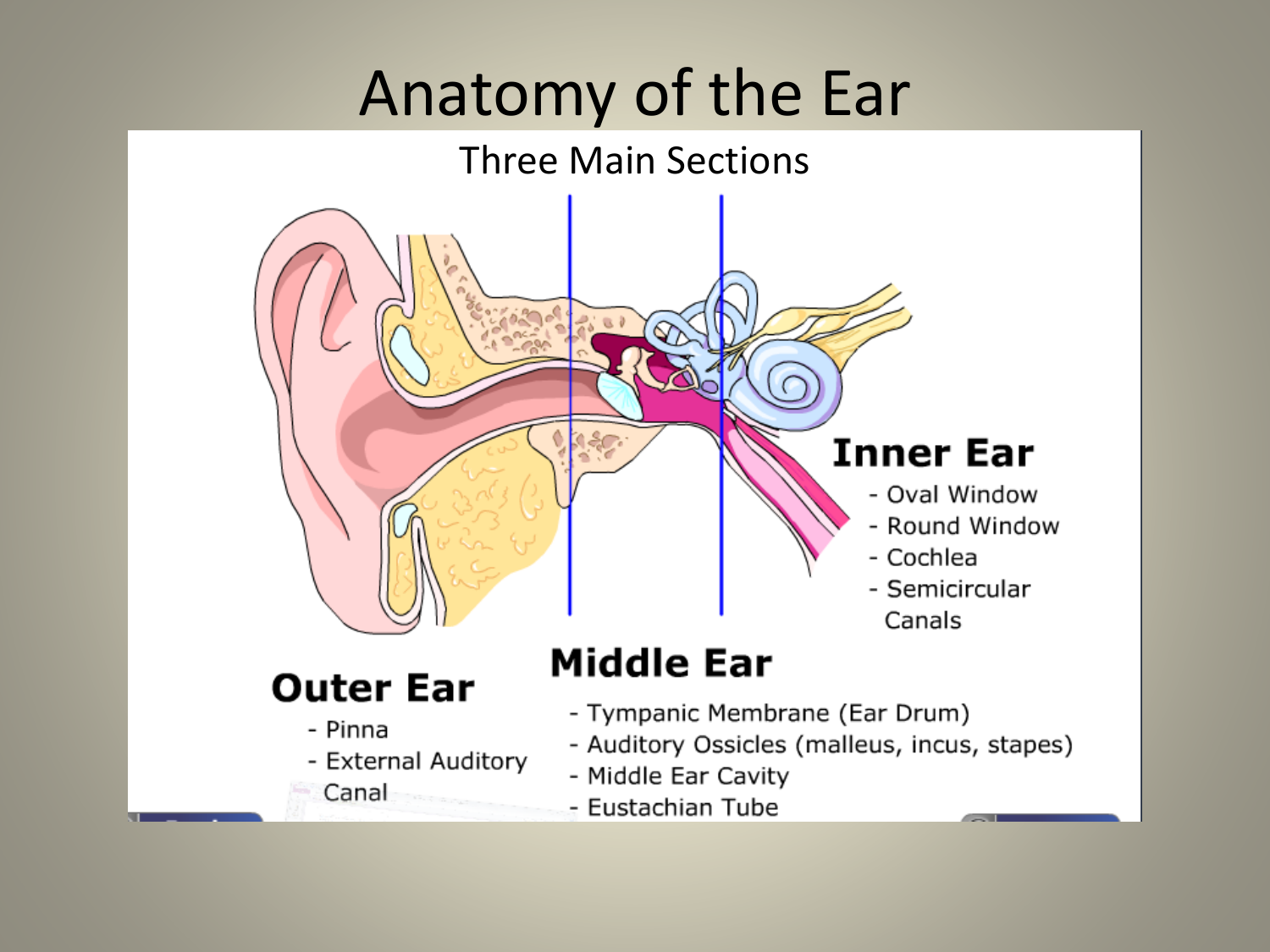

Let’s start with the part you can actually see in the mirror. In any standard diagram of the ear with labels, this is the "Outer Ear." The floppy part on the outside is the pinna. It’s not just there to hold up your glasses or look good with earrings. The ridges and valleys of your pinna are uniquely shaped to funnel sound waves into the ear canal. Interestingly, the specific shape of your ear helps you determine if a sound is coming from above you or behind you.

The ear canal, or the external auditory meatus if you want to be fancy, is basically a dead-end street. It’s about 2.5 centimeters long. Its main job is to protect the eardrum and act as a natural resonator. It actually boosts sounds in the 2,000 to 5,000 Hz range—which happens to be where human speech is most clear. Evolution really wanted us to hear each other talking.

Then there’s the wax. Cerumen. We hate it, we dig it out with Q-tips (which you shouldn't do, by the way), but it’s the ear’s self-cleaning mechanism. It’s acidic and fatty. It keeps bugs out and prevents the skin from drying out.

The middle ear: Where the physics gets weird

Once the sound hits the eardrum—the tympanic membrane—everything changes. This is the boundary. On one side, you have air. On the other side... well, you still have air, but it’s a pressurized chamber. This is where the ossicles live. These are the three smallest bones in your entire body.

💡 You might also like: Images of Grief and Loss: Why We Look When It Hurts

The Malleus (Hammer), Incus (Anvil), and Stapes (Stirrup).

If you look at a diagram of the ear with labels focusing on the middle ear, you'll see these bones are connected in a chain. When the eardrum vibrates, it pushes the hammer. The hammer hits the anvil. The anvil pushes the stirrup. But why? Why not just have the eardrum hit the inner ear directly?

Physics.

The inner ear is filled with fluid, not air. If you’ve ever tried to listen to someone talking while you’re underwater in a swimming pool, you know that sound doesn't travel well from air to water. Most of the energy just bounces off the surface. The ossicles act as a mechanical lever system. They concentrate the vibration from the relatively large eardrum onto the tiny "oval window" of the inner ear. This increases the pressure by about 22 times. Without these three tiny bones, the world would sound like you were wearing heavy-duty earmuffs 24/7.

The Inner Ear and the Cochlea’s secret

This is where the magic—and most of the permanent damage—happens. The cochlea looks like a snail shell. Inside that shell are thousands of microscopic hair cells called stereocilia.

When the stirrup bone pushes against the cochlea, it creates a wave in the fluid. That wave moves the hair cells. High-pitched sounds vibrate the hairs at the very beginning of the snail shell. Low-pitched sounds travel all the way to the center.

📖 Related: Why the Ginger and Lemon Shot Actually Works (And Why It Might Not)

Here is the kicker: those hair cells don't grow back.

Unlike a lizard that can regrow a tail or your skin that heals after a scrape, once a hair cell in your cochlea is flattened by a loud concert or a firework, it’s dead. This is why "hidden hearing loss" is such a big deal. You might pass a standard hearing test, but if you struggle to hear a friend in a noisy restaurant, it’s because those specific "tuning" hairs are gone.

The Balance Equation: Semicircular Canals

Often, a diagram of the ear with labels will include three loops sitting on top of the cochlea. These are the semicircular canals. They have absolutely nothing to do with hearing.

They are your internal gyroscopes.

They are filled with fluid and lined with more hair cells. When you tilt your head or spin in circles, the fluid lags behind due to inertia, bending the hairs and telling your brain exactly where you are in 3D space. This is why vertigo feels so world-ending; it’s a hardware error in these tiny loops. If you’ve ever had an inner ear infection and felt like the floor was tilting, you can blame a glitch in this specific labeled section of the diagram.

Why the Eustachian Tube is your best friend (and worst enemy)

Connecting the middle ear to the back of your throat is a thin straw called the Eustachian tube. Its only job is to equalize pressure. When you’re on a plane and your ears "pop," that’s this tube opening up to let air in or out so your eardrum doesn't rupture.

👉 See also: How to Eat Chia Seeds Water: What Most People Get Wrong

In kids, this tube is shorter and more horizontal. That’s why toddlers get so many ear infections. Bacteria from the throat can just crawl right up there. As you get older, the tube becomes more vertical, making it harder for "gunk" to get stuck, though it can still happen during a bad cold.

Common misconceptions about the ear diagram

Most people think the eardrum is deep inside the head. It's actually only about an inch in. This is why "don't put anything smaller than your elbow in your ear" is real advice. A slip of a cotton swab can easily reach the tympanic membrane.

Another myth is that "nerve deafness" is always about the brain. Usually, it's just the hair cells in the cochlea failing to send the signal. The nerve itself is often fine, but the "batteries" (the hair cells) are dead.

Protecting the hardware: Actionable steps for ear health

Understanding the diagram of the ear with labels isn't just for passing a test; it’s about maintenance. Since we know the hair cells in the cochlea are finite and fragile, protection is the only real strategy.

- Follow the 60/60 rule: Listen to music at no more than 60% volume for no more than 60 minutes at a time. This gives the stereocilia time to recover from the "noise fatigue" before permanent damage sets in.

- The "Finger Test" at concerts: If you have to shout for someone standing an arm's length away to hear you, the environment is loud enough to be causing microscopic damage to your middle and inner ear.

- Dryness is key: After swimming, tilt your head to ensure the ear canal is clear. Dampness leads to "swimmer's ear," which is an infection of the outer ear canal skin, not the inner works.

- Stop the digging: Cerumen (wax) moves outward naturally. Using a tool to "clean" it usually just packs the wax against the eardrum, which can dampen the vibration of the ossicles and make you feel like you’re underwater.

If you ever experience a sudden drop in hearing—especially in only one ear—don't wait. That is a medical emergency often related to the inner ear's blood supply or a viral attack on the auditory nerve. Seeing an audiologist or ENT within 48 hours can often save your hearing through steroid treatments, whereas waiting two weeks usually means the loss is permanent.