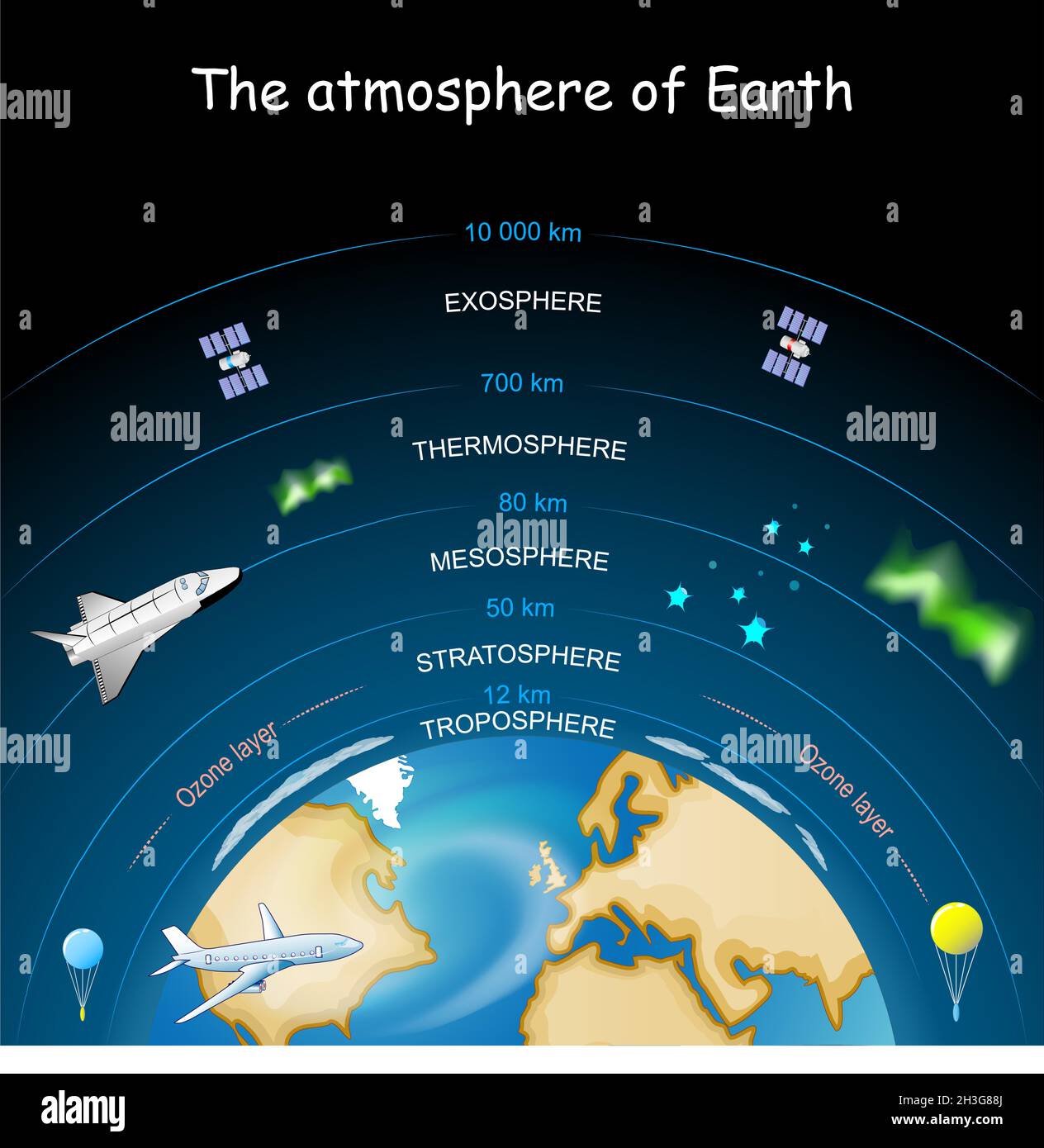

You probably remember it from middle school. A simple, colorful diagram of Earth's atmosphere showing five neat layers stacked like a birthday cake. Troposphere at the bottom, exosphere at the top, and some clouds sprinkled in for good measure. It looks orderly. It looks static.

But honestly? That's a total oversimplification.

The air above your head isn't just a series of blankets. It is a violent, shifting chemical laboratory influenced by solar radiation, magnetic fields, and human activity. If you look at a truly accurate diagram of Earth's atmosphere, you realize we live in a thin, fragile skin of gas that protects us from a literal vacuum of death. It's not just "air." It's a shield.

The Troposphere is Where the Chaos Happens

This is our home. The troposphere contains about 75% to 80% of the atmosphere's entire mass. It’s thin. Really thin. Depending on where you are—like at the equator versus the poles—it only stretches about 5 to 9 miles high.

Everything you recognize as "weather" happens here. It's the only layer where we can actually breathe without equipment. But here is the weird part: in this layer, the higher you go, the colder it gets. This is why mountains have snow caps even in the summer. The ground absorbs sunlight and heats the air from the bottom up.

Most people don't realize that the boundary at the top, called the tropopause, acts like a ceiling. It’s where the cooling stops. Pilots love flying just above this because it’s where the air stabilizes, and you get away from the bumpy convection currents that cause turbulence. If you’ve ever looked out a plane window and seen the top of a massive thunderhead cloud looking "flat," you’re seeing the tropopause in action. The cloud literally hit the ceiling.

The Stratosphere and the Ozone Myth

Above the ceiling is the stratosphere. This layer goes up to about 31 miles. Unlike the layer below it, the stratosphere actually gets warmer as you go higher.

Why? Because of the ozone layer.

💡 You might also like: The H.L. Hunley Civil War Submarine: What Really Happened to the Crew

Ozone molecules ($O_3$) are busy absorbing ultraviolet (UV) radiation from the sun. That absorption releases heat. When you look at a diagram of Earth's atmosphere that includes a temperature line, you'll see a sharp "zag" to the right in this section.

There's a common misconception that the ozone layer is a thick "shield" or a solid wall. In reality, it’s incredibly sparse. If you took all the ozone in the stratosphere and brought it down to sea level pressure, it would be about 3 millimeters thick. That’s it. Just two pennies stacked together. Yet, without those few millimeters of gas, complex life on land wouldn't exist. The UV-B and UV-C rays would basically sterilize the planet's surface.

Scientists like Paul Crutzen and Mario Molina, who won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1995, showed us just how easily human-made chemicals like CFCs could tear holes in this thin veil. We’ve spent the last few decades trying to fix it through the Montreal Protocol, and it’s working, but the stratosphere remains a delicate balancing act.

The Mesosphere: The Forgotten Middle Child

If the troposphere is for weather and the stratosphere is for ozone, the mesosphere is for meteors.

This layer, extending to about 53 miles high, is arguably the most mysterious. It’s too high for weather balloons and too low for most satellites to orbit without burning up. Scientists often call it the "ignorosphere" because it’s so hard to study directly.

It is also the coldest place on Earth. Temperatures here can plummet to $-130^\circ F$ ($-90^\circ C$). This is where space truly begins to interact with our air. When a space rock hits our atmosphere at 25,000 miles per hour, the friction in the mesosphere burns it up. Those "shooting stars" you see? That’s the mesosphere doing its job as a kinetic shield.

You might also see "noctilucent clouds" here. They are these eerie, glowing blue clouds made of ice crystals that form on "meteor smoke"—the tiny dust particles left behind by disintegrated space rocks. You can only see them at twilight when the sun is below the horizon but still hitting these ultra-high-altitude clouds.

📖 Related: The Facebook User Privacy Settlement Official Site: What’s Actually Happening with Your Payout

The Thermosphere and the Border of Space

Then things get hot. Or, well, "hot" in a way that’s hard to wrap your head around.

The thermosphere starts at the mesopause and goes out to about 372 miles. Temperatures here can soar to $4,500^\circ F$ ($2,500^\circ C$). You might think you’d be incinerated, but you’d actually freeze to death.

Temperature is a measure of kinetic energy—how fast molecules are moving. In the thermosphere, the few molecules that exist are moving incredibly fast because they’re being hit by high-energy X-rays and UV radiation. However, the air is so thin—almost a vacuum—that there aren't enough molecules to actually transfer that heat to your skin.

This is where the International Space Station (ISS) hangs out. It’s also where the Aurora Borealis (Northern Lights) happens. Charged particles from the sun collide with oxygen and nitrogen atoms in the thermosphere, "exciting" them and causing them to emit light.

- Green light: Oxygen atoms at lower altitudes.

- Red light: Oxygen atoms at very high altitudes.

- Blue/Purple light: Nitrogen.

The Exosphere: Where Gravity Gives Up

The final frontier of any diagram of Earth's atmosphere is the exosphere.

This is the "fringe." There isn't a hard line where the atmosphere ends and space begins. Instead, the atoms just get further and further apart until they eventually drift away into the solar wind.

Hydrogen and helium are the main players here. The "air" is so thin that a single atom might travel hundreds of miles without ever hitting another atom. Technically, the exosphere can extend up to 120,000 miles—halfway to the moon.

👉 See also: Smart TV TCL 55: What Most People Get Wrong

Why This Structure Actually Matters for You

It’s easy to look at these layers as just academic trivia. They aren't.

Understanding the atmospheric gradient is vital for modern technology. Our GPS satellites, for instance, have to account for the ionosphere—a region within the thermosphere and mesosphere where the sun strips electrons from atoms. These free electrons can slightly delay the radio signals from satellites. If we didn't understand the "density" and "charge" of these layers, your Google Maps would be off by dozens of meters.

Moreover, the atmosphere is currently changing.

As we pump more $CO_2$ into the troposphere, it traps heat. But a weird side effect is that while the bottom layer warms up, the upper layers—specifically the stratosphere and mesosphere—are actually cooling down. This "shrinkage" of the upper atmosphere changes how satellites orbit and how space junk decays.

Actionable Steps for Deepening Your Knowledge

If you're looking to move beyond a static diagram of Earth's atmosphere and see it in action, here’s how to do it:

- Track the ISS: Use apps like "ISS Detector" to see the thermosphere in action. When you see that bright light moving across the sky, you’re looking at a human habitat sitting inside the hottest layer of our atmosphere.

- Monitor the Ozone Hole: Visit NASA's Ozone Watch website. It’s updated daily and shows the actual "thickness" of the stratosphere’s protective layer in Dobson Units.

- Watch for Noctilucent Clouds: If you live in high latitudes (like the Northern US, Canada, or Europe) during the summer, look North about 30–60 minutes after sunset. If you see electric-blue, wavy clouds, you are seeing ice crystals 50 miles up in the mesosphere.

- Use a Barometer: Even a cheap digital one or the sensor in your smartphone can show you the "weight" of the troposphere. Watch the pressure drop as you drive up a hill; you are literally feeling the thinning of the atmosphere in real-time.

The atmosphere isn't a static object. It's a breathing, reacting system of gas and energy. Next time you look at a diagram, remember: you’re looking at the only reason the Earth isn't a frozen, irradiated rock like the moon.